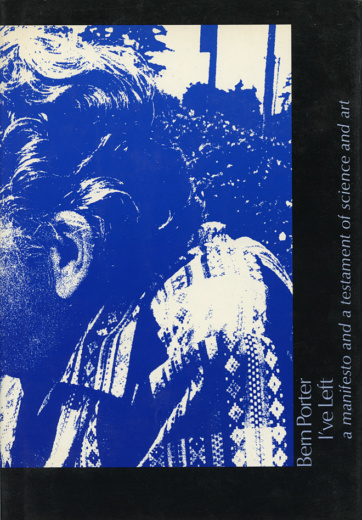

jwcurry writes:

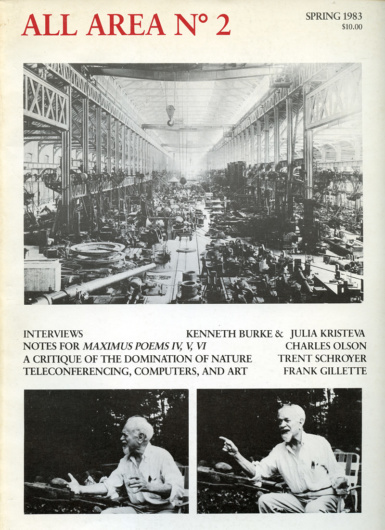

Underwhich Editions was/is a multiply-unique publishing coöperative that issued primarily from Toronto (with some blurts from Saskatoon & Sault Sainte Marie) into & throughout the 198os, its final(?) publication released in 1998.

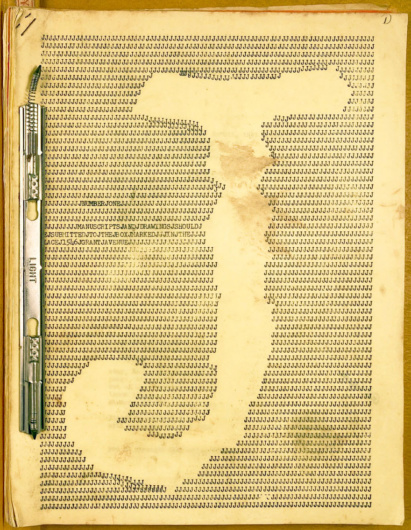

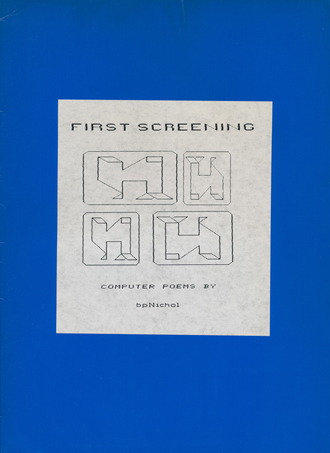

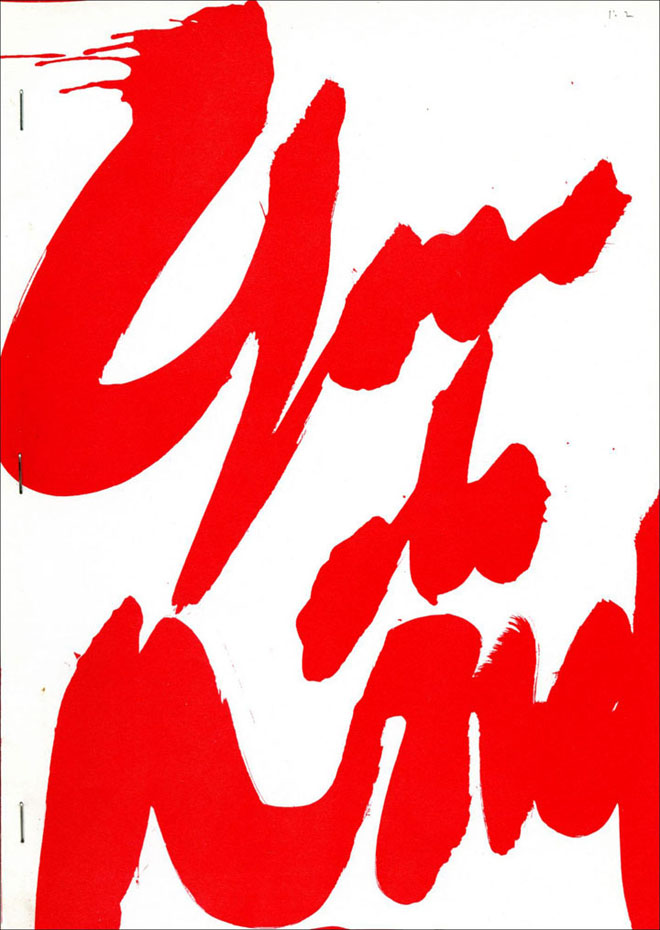

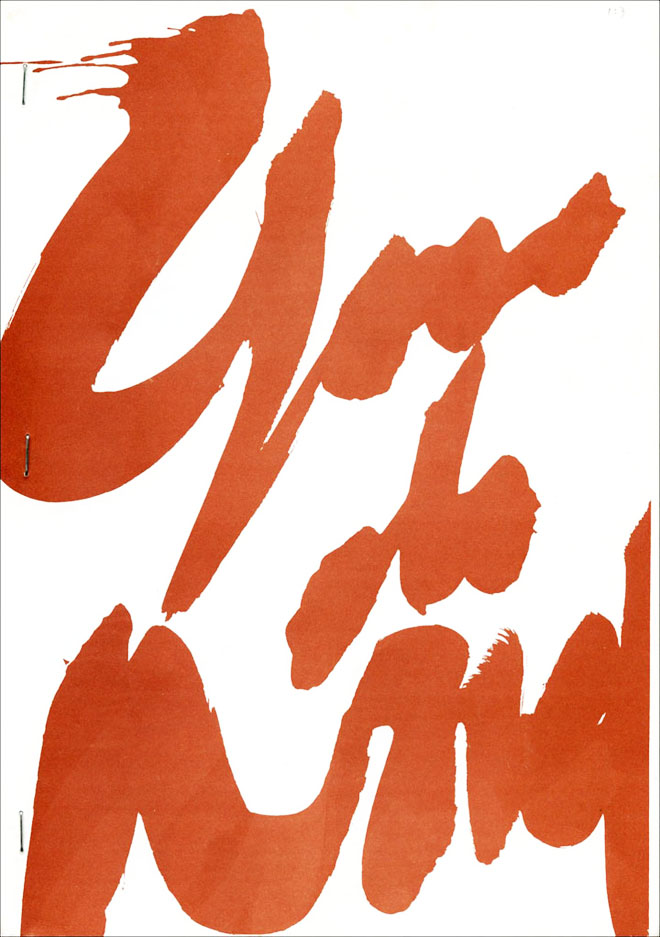

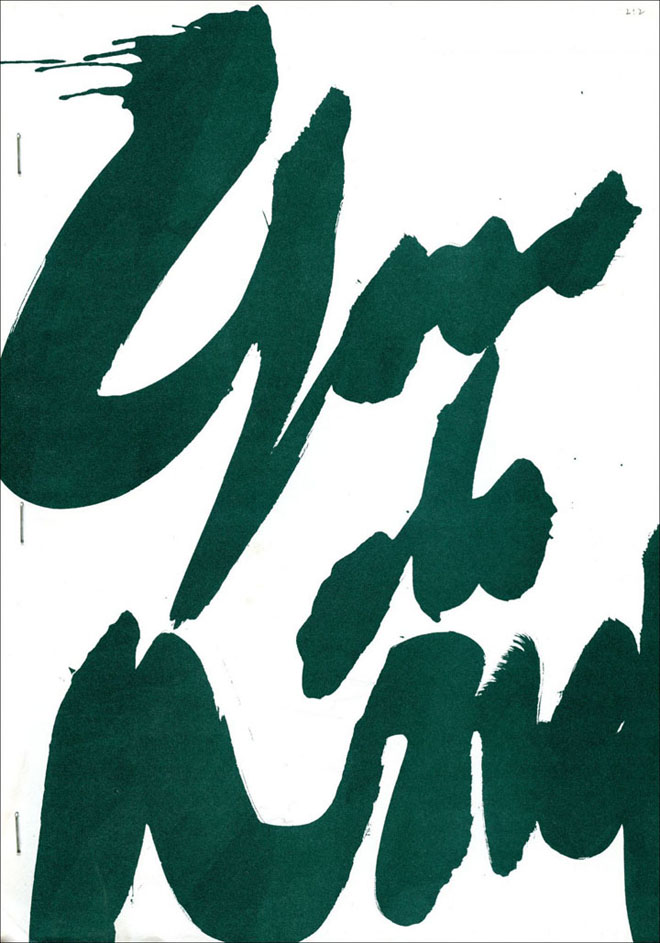

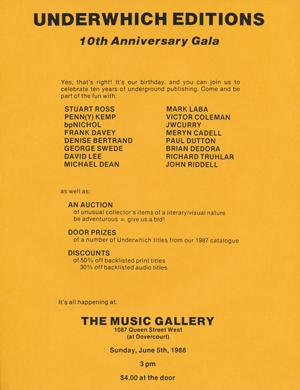

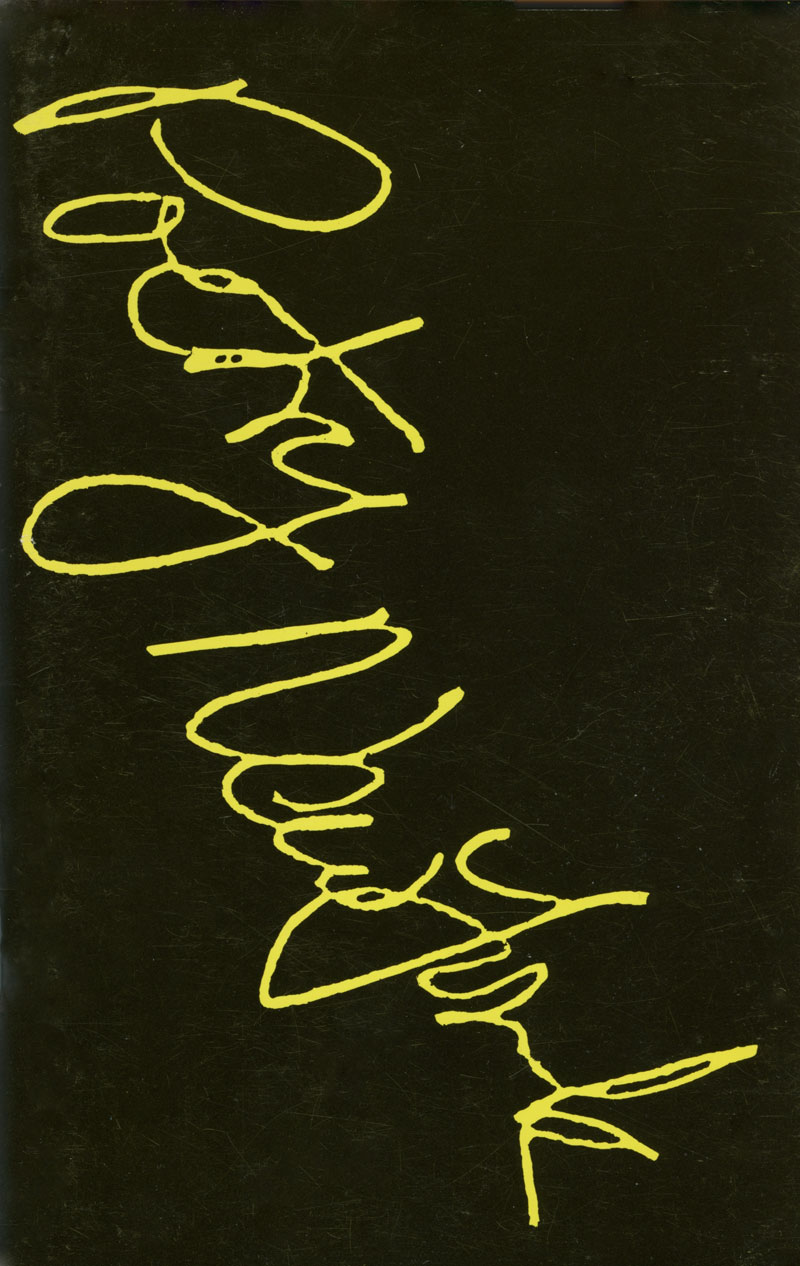

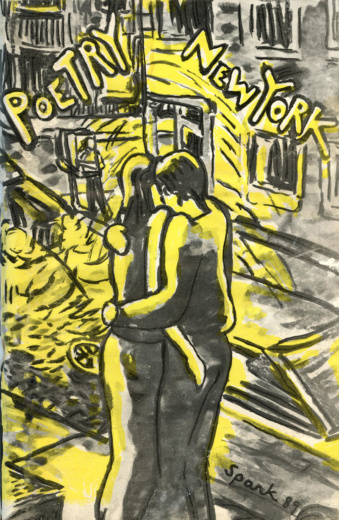

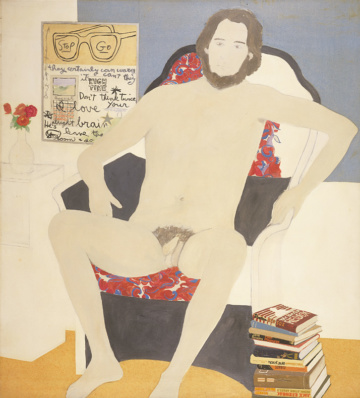

bpNichol, artist. [Underwhich Editions 10th Anniversary Gala Poster]. The Music Gallery, June 5, 1988.

in 1978, a consortium of Toronto publishers conspired to produce the 3rd volume of Bob Cobbing’s collected poems, a peal in air. bpNichol had been running Ganglia Press since 1965; Steve McCaffery’s Anonbeyond Press had released a handful of fugitive publications since 197o; Michael Dean’s Wild Press had just gotten going early in 1975; Richard Truhlar’s Phenomenon Press began its series of remarkable releases in 1976. the Cobbing collection came out with all imprints attached – bibliographically clunky perhaps but a fine way of citing a group effort of support.

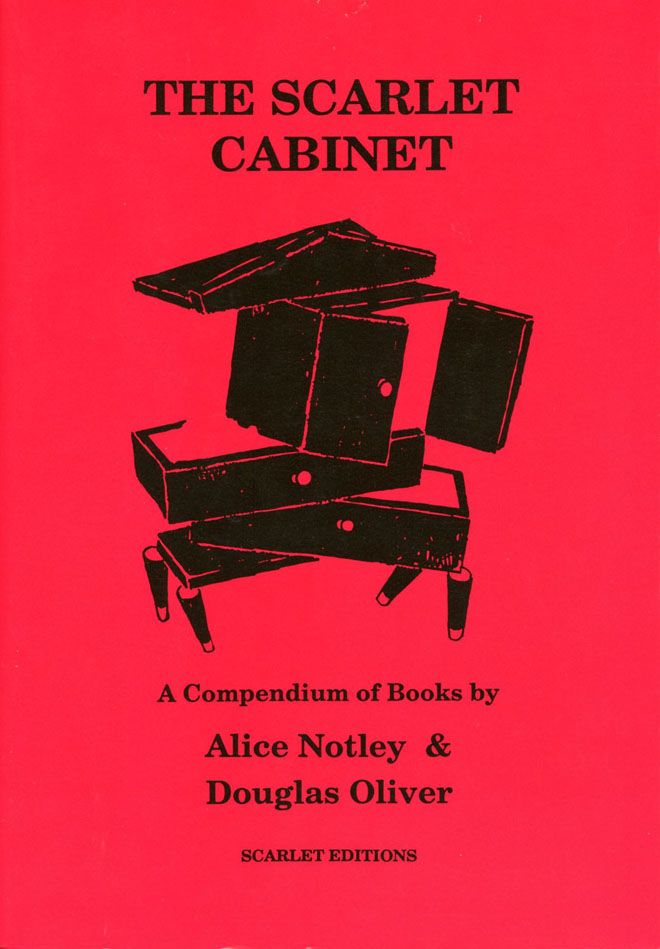

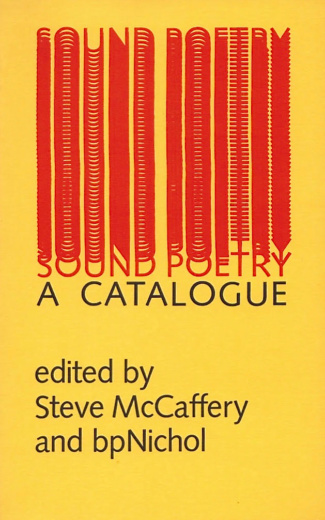

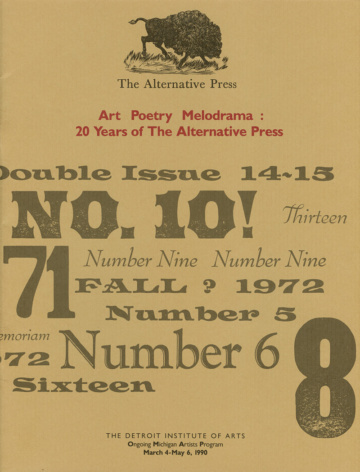

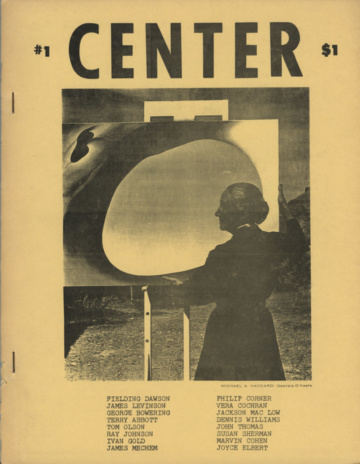

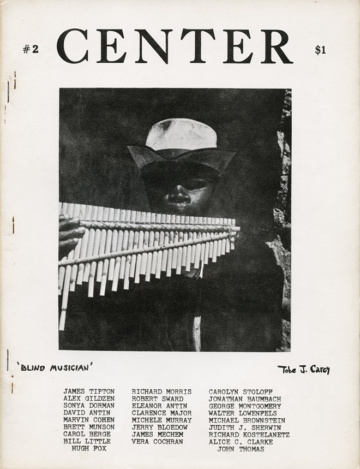

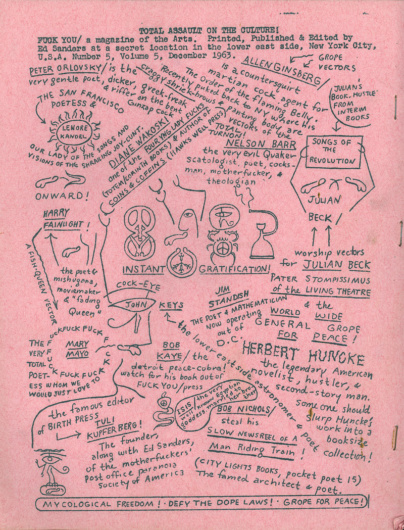

simultaneous with this, preparations were underway for the 11th International Festival of Sound Poetry in Toronto. previous festivals had generated some extravagant productions, primarily in the form of posters & programmes, with Michael Gibbs’ anthology Kontextsound accompanying the 1oth in Amsterdam (i can find no references to any previous anthological souvenirs). McCaffery & Nichol kicked things up several notches with the preparation of Sound Poetry: A Catalogue: 111 pages of scores, essays, photographs & capsule biographies, all stunningly designed by master typographer Glenn Goluska. this was going to want something a little more deliberate by way of an imprint in stead of the hodgepodge of Presses decorating the colophon of the Cobbing book.

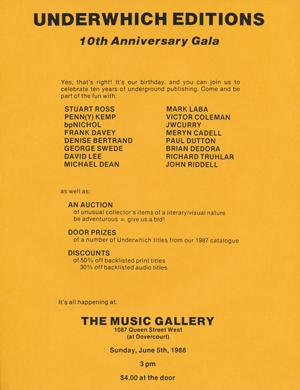

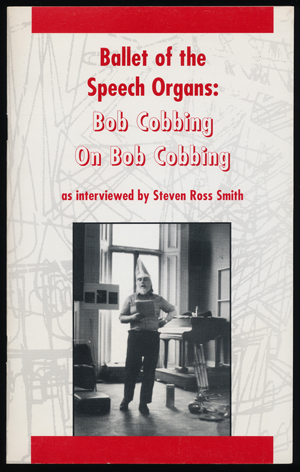

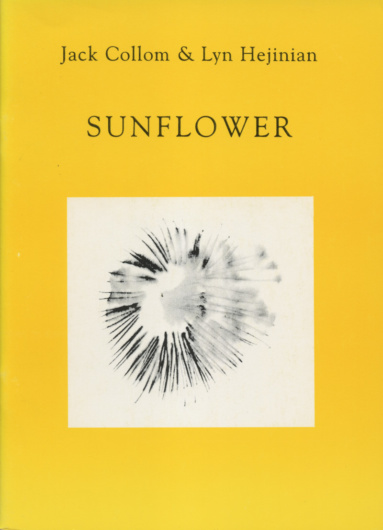

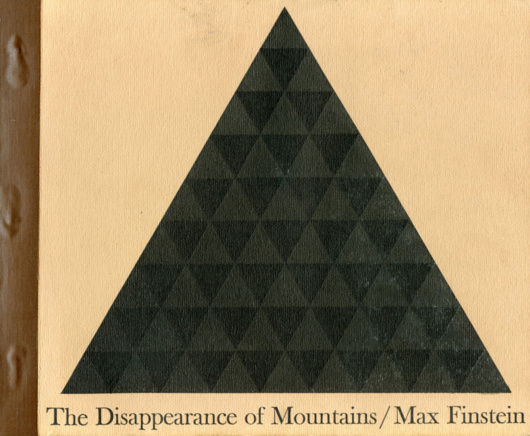

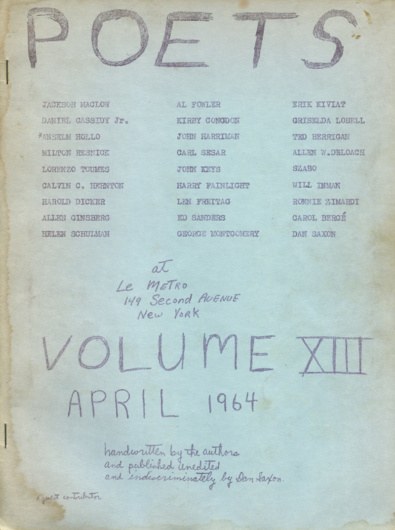

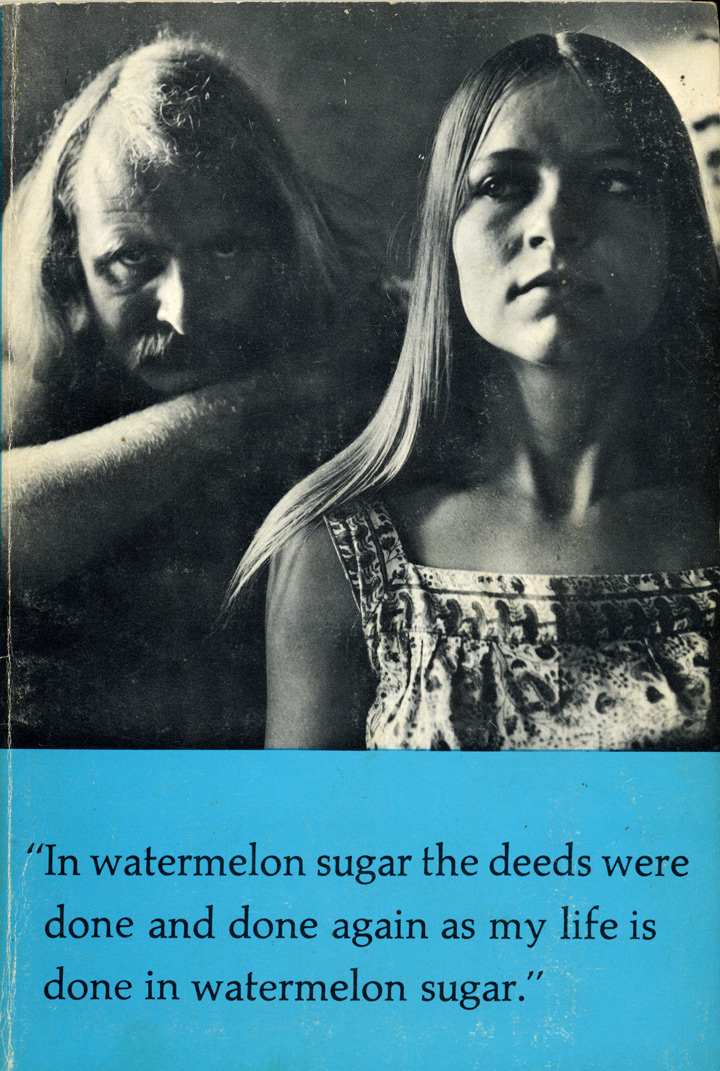

Bob Cobbing and Steven Ross Smith. Ballet of the Speech Organs: Bob Cobbing On Bob Cobbing. Underwhich Editions, 1998.

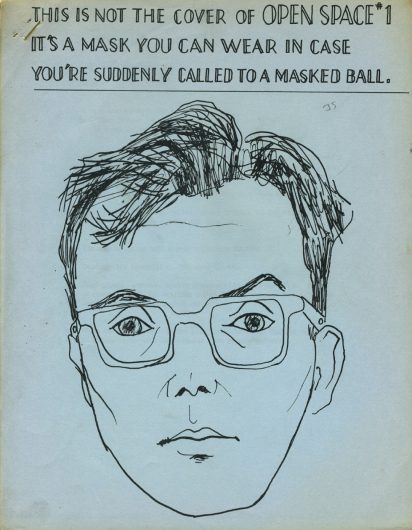

John Riddell had been involved in both Ganglia & Phenomenon, & Brian Dedora & Paul Dutton were in the middle of it all with no imprints of their own but hot to participate. as the anthology grew toward completion, the question became: “under which imprint do we release this beast?”, thus providing its own answer in the very statement of the problem. with an intentionality toward producing things other than standard small press fare (the cover of the first catalogue pronounces “a fusion of high production standards and top-quality literary innovation”), the word “editions” was chosen as most representative of that focus & Underwhich Editions was launched at the festival with not only the anthology but a catalogue listing a further 4 print titles (by Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Dedora, McCaffery & R.Murray Schafer) & 2 cassettes (by McCaffery).

Underwhich Editions, formed in exigency at a critical period in & when Toronto had a greater complement of so-called “experimental” writers than anywhere else on the planet, grew quickly into the gap left by Coach House Press’s domestication. the only other Canadian publishers that paid primarily lipservice to the more challenging areas of literary production didn’t go very far outta their way to support the avant garde, gasping out a title or 2 every coupla years orso (witness Oberon, who made a splash in 197o with 2 bpNichol titles, instigated their own attempt at a series focussing on concrete/visual poetry with the release of Four Parts Sand, then bailed & went back to storytelling & conservative criticism). besides a smattering of the what’re now called “micropresses” (& it is to be remembered that micropresses are just as much part of the problem as any other demographic, serving primarily to further their own interests in the face of the greater disdain, most of anything that gets published usually wallowing in much-trampled LCD mud), noöne else seemed to give a shit about the vast amount of worldclass material being produced in Canada, much less anything beyond the pond. & while some of the micropresses maintained a respectably constant engagement in making challenging work available, few of them had the budget for grander gestures, nor the patience for building larger structures over time.

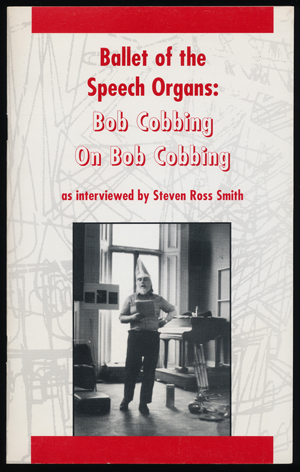

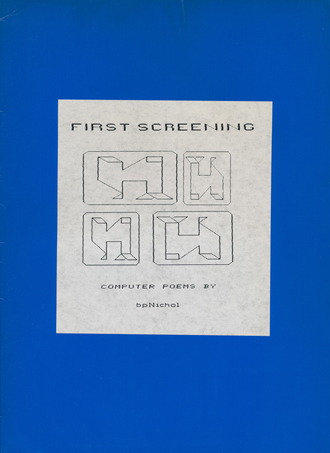

bpNichol. First Screening: Computer Poems. Underwhich Editions, 1984.

with its conspiratorial core of 8 (Dean, Dedora, Dutton, McCaffery, Nichol, Riddell, Smith, Truhlar), all given editorial independence in a spirit of mutual trust & understanding of the underlying mandate (again from the cover of the first catalogue: “…dedicated to presenting, in diverse and appealing physical formats, new works by contemporary creators, focusing on formal invention and encompassing the expanded frontiers of literary endeavour.”), Underwhich virtually exploded into action with an initial series of smaller works from almost all editors, each given the physical attention they deserved to become fully-realized works of book art in addition to their values as literary artefacts. editors were free to do what they wanted & could also join forces to pool resources for the production of more involved titles.

i vividly remember the first Underwhich book i saw: a little pile of LeRoy Gorman’s Whose Smile The Ripple Warps (198o) stacked face-up somewhere in Paul Stuewe’s Nth Hand Books on Harbord Street, Toronto, in later 198o. consisting entirely of typestract miniatures that function somewhat on the level of haiku, the small book gives each piece ample room without dwarfing them in a slender, perfectbound volume that suggests, through its very simple cover, “here is something beautiful”. the only thing it lacked was ostentation, which was in far greater unwanted supply elsewhere. it was, in fact, beautiful; in further fact, it still is beautiful & never won’t be. what the fuck more could one possibly ask for? (i suppose a signed copy…)

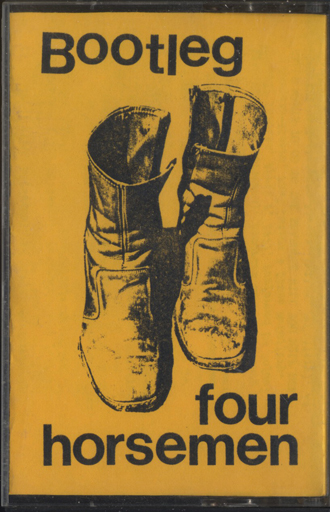

Four Horsemen. Bootleg. Underwhich Editions, 1981.

almost all the material coming outta Underwhich provoked further investigation of the press itself & those whose work it produced (& those who produced it). it also provoked interest in others in joining in its collective identity, all of whom came to Underwhich through an active editor’s kind-of-sponsorship & bringing with them their own experience with publishing through their own imprints. over the years, other active participants were jwcurry (of Curvd H&z, Industrial Sabotage, et al), Beverley Daurio (Mercury Press, Paragraph), Frank Davey (Massassauga Editions, Open Letter), Mary Stevens Grace, Karl Jirgens (Rampike), & Jim Smith (The Front Press).

except for a brief flirtation with a distributor, Underwhich advertised its material primarily by mail &, lesserly, at various book fairs. it also began promoting publications from other publishers that they felt fit their evolving model.

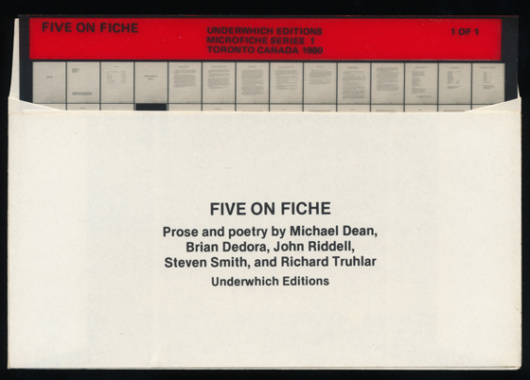

Richard Truhlar, ed. Five on Fiche. Underwhich Editions, 198o. Issued as Microfiche Series 1.

Underwhich Editions was an absolutely unique occurrence in Canadian publishing history. its dissolution occurred following the slow dispersion of many of its constituents: curry to Ottawa, Davey to London, Dedora to Vancouver, Jirgens to Sault Sainte Marie, McCaffery to Buffalo, Nichol’s death, & Steven Smith to Saskatoon (where he gamely continued on for awhile as the “prairie branchplant”). apparently, Lucas Mulder & Lia Pas also supplemented the skeleton with Dutton & Smith at the end of its active phase.

its many accomplishments are unique figures on the mulched ground of Canadian literature.

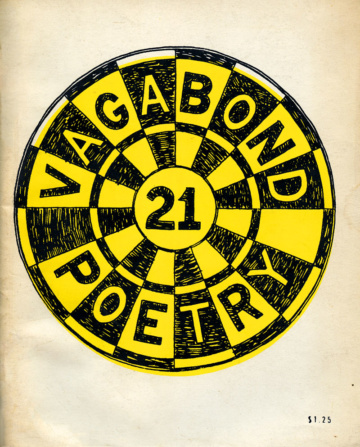

[18 regular-issue catalogues]. Underwhich Editions, 1979–1996.

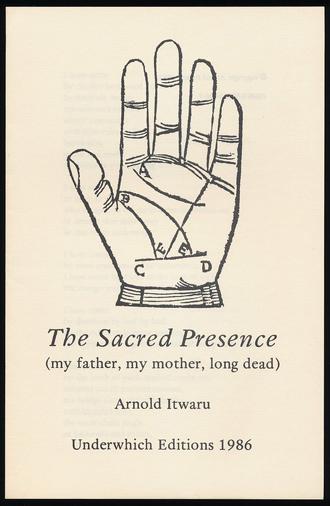

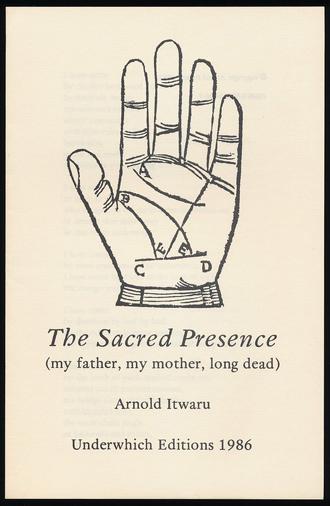

ITWARU (Arnold). The Sacred Presence (my father, my mother, long dead). Underwhich Editions, 1986.

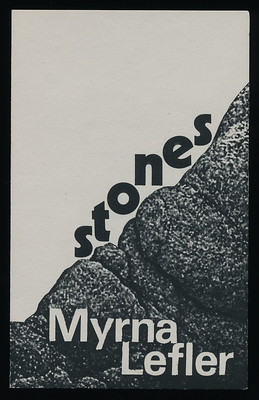

LEFLER (Myrna) stones. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately. 4 pp/3 printed, photocopy. 2-3/4 x 4-1/4, leaflet. a poem.

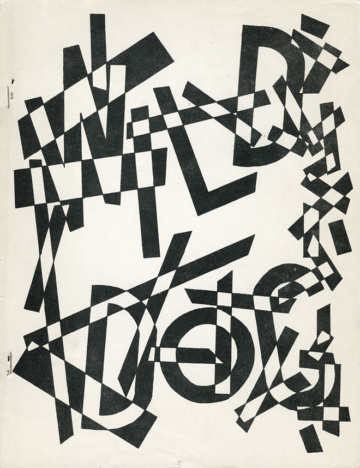

McCAFFERY (Steve) Epithalamion for the marriage of Marjeceta Cujes to Salvatore Incardona. Mono Hills, Dufferin County 3o September 1978. [Toronto], Underwhich Editions, january 1979. 3oo #d copies. 4 pp printed, offset. 5 x 1o, leaflet. an uncommonly subjective lyricism to this poem for 2 friends that McCaffery refuses to talk about (& which he attempted to destroy the run of), braced by 2 anagrammatical concrete cover tableaux. one of the 1st batch of Underwhich publications.

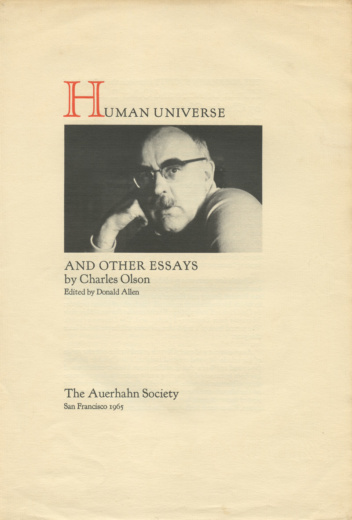

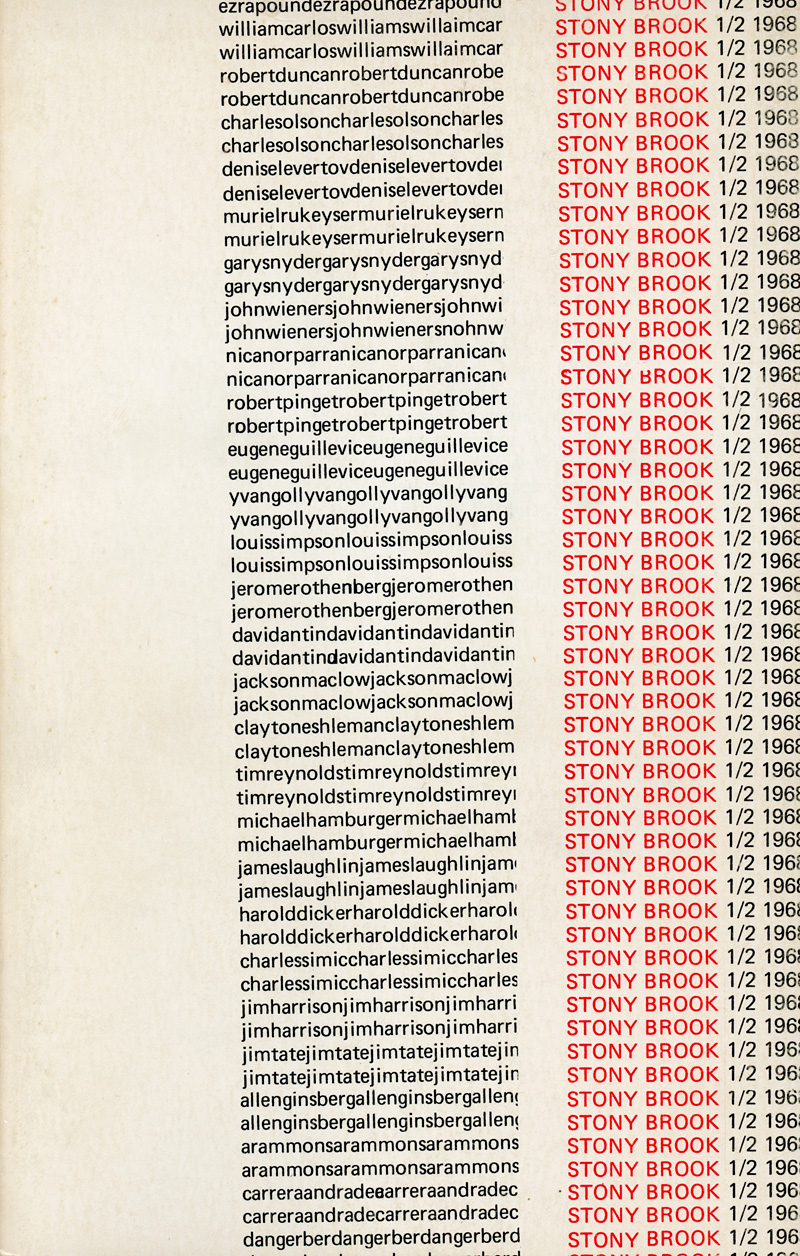

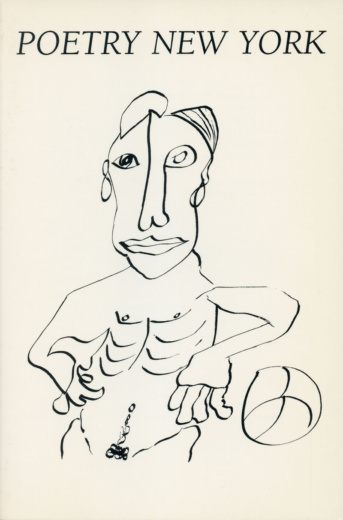

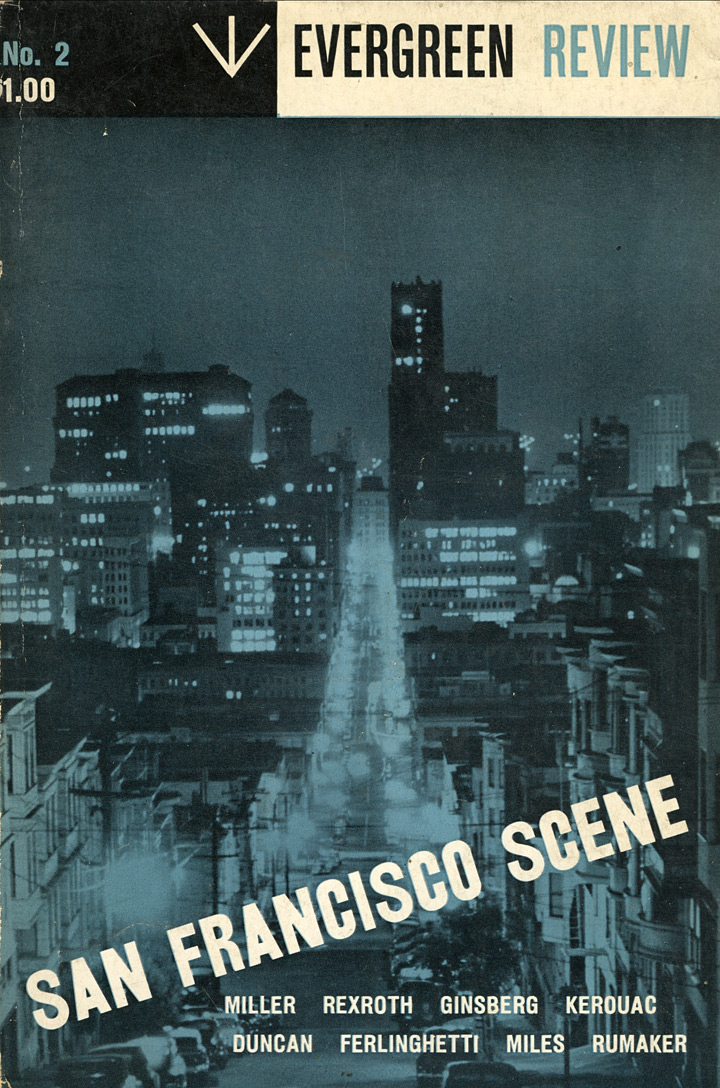

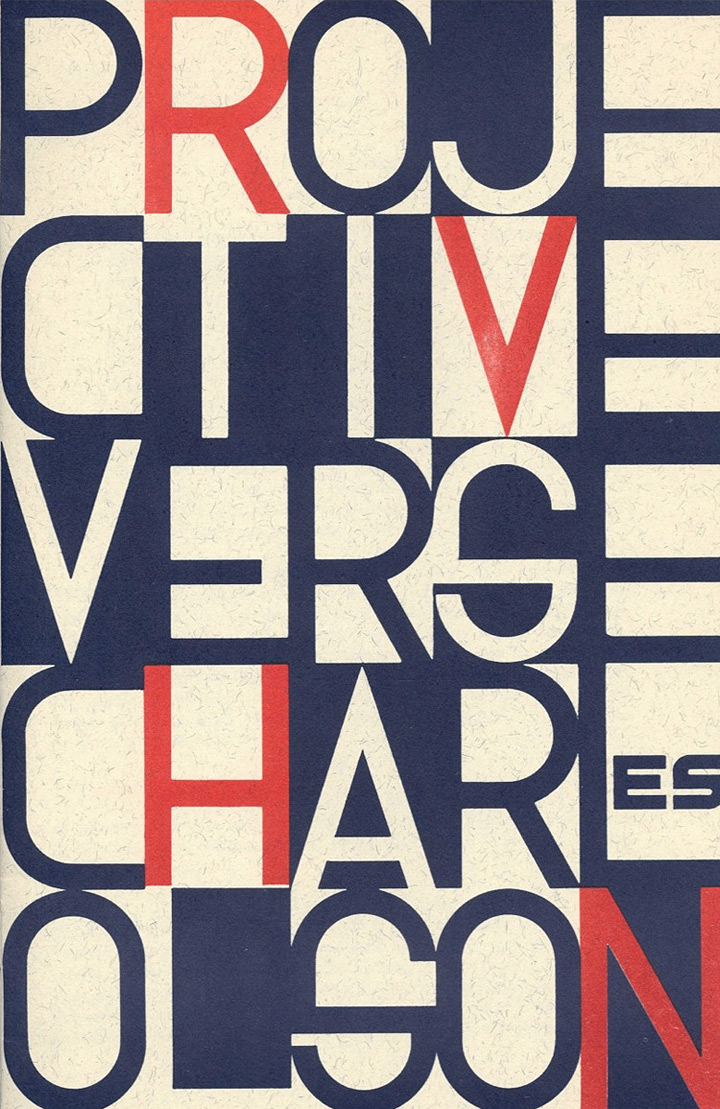

McCAFFERY (Steve) & bpNichol, eds Sound Poetry: A Catalog. (1978).

NICHOL (bp) FIRST SCREENING. Computer Poems. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 28 september 1984. 1oo copies #d & signed, issued as Software Series #1. a 5-1/4 x 5-1/4 plastic floppy disc (compatible with Apple 2e of ago) in paper pocket, both with dotmatrix labels, in 8-11/16 x 11-15/16 pocketed folder with interior & exterior labels & 8-1/2 x 11 photocopied broadside A Few Notes opposite. animated concrete poetry. this was posthumously reprinted by Red Deer College Press as a now equally-obsolete miniharddisc; “for the collection”.

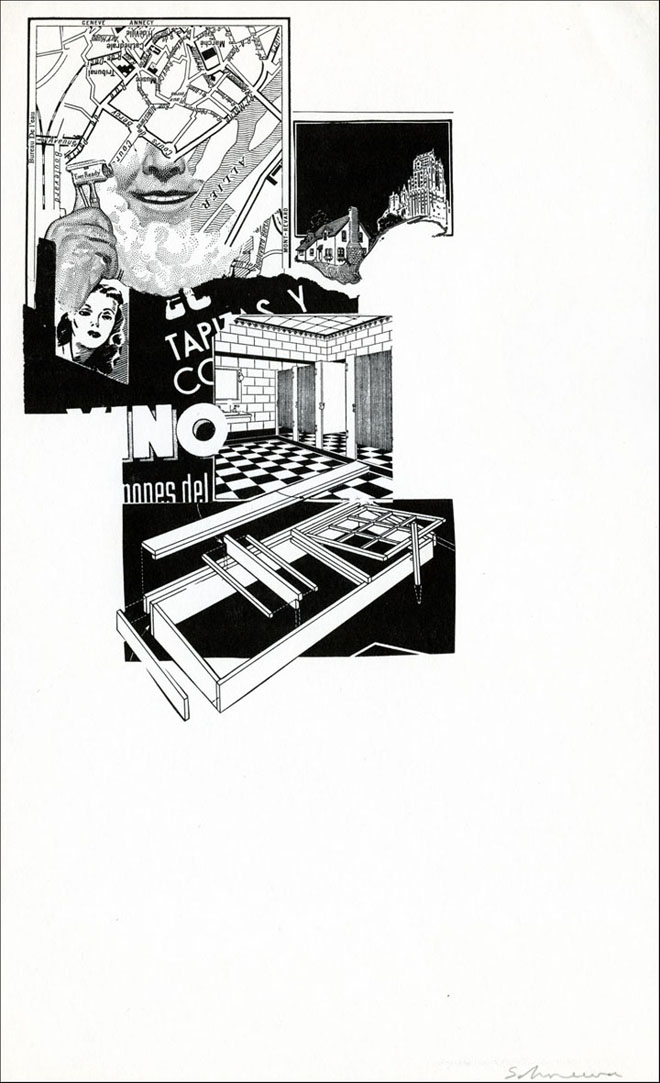

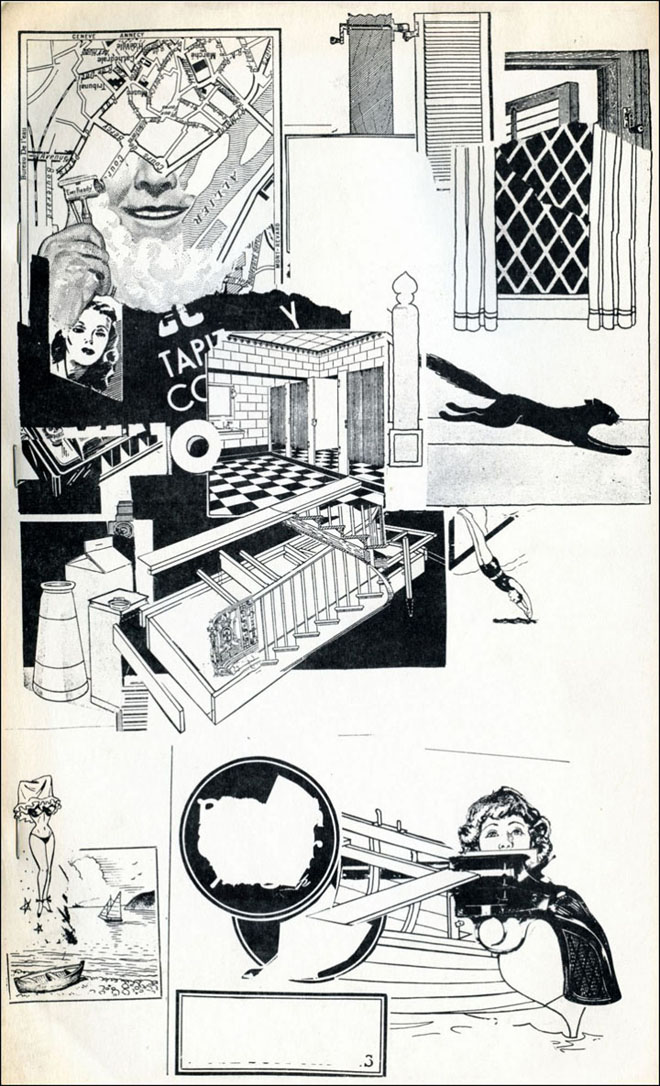

NICHOL (bp) [Underwhich Editions 10th Anniversary Gala Poster]. The Music Gallery, June 5, 1988.

OWEN SOUND (Michael Dean, David Penhale, Steven Smith, Richard Truhlar) SIGN LANGUAGE. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1985. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographic Series #22. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min. audiocassette with 6 pp offset J-card in hinged plastic box. sound poetry. includes a version of Robert Ashley’s She Was A Visitor with the added voices of Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery & bpNichol.

PAUL (David J) FLOOD. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, rubberstamp. 3-7/16 x 1-1/4, leaflet. a concrete poem.

PHENOMENØNSEMBLE (Kathy Browning, Nick Dubecki) NON. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, may 1986. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographic Series #28. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min.audiocassette & 8pp offset J-card in hinged plastic box. music. with contributions by Anne Bourne, Stephen Donald, Jeff Packer, Rik Sacks, Richard Truhlar.

RIDDELL (John) D’Art Board. Toronto, Underwhich Editions,1987. not released separately. 6 pp printed, photocopy. 3-3/4 x 8-1/2, leaflet. the instruction sheet for Riddell’s version of a game of darts, which had been issued by Underwhich as a large broadside. this accompanied that but also accompanied a small mini-darts desk set that he issued privately in a very small edition of one-off constructions for friends.

ROSS (Stuart) ” “Definitely not “. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, photocopy. 3-1/2 x 3-1/4, leaflet. a poem.

RUNNING HEAD. poetry/graphics. edited by jwcurry. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 7 december 1983. 5o #d copies signed by all contributors: Joe Brouillette, curry, Mark Laba, Peggy Lefler, bpNichol, George Swede. 5-1/2 x 8-1/2, 6 silkscreen broadsides & rubberstamp colophon leaf with tissue interleaving in plain sleeve with acetate window. poetry, concrete poetry & graphics.

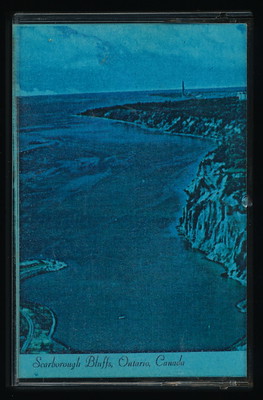

SCARBOROUGH SOUND SYMPHONY (conducted by Michael Dean) SCARBOROUGH BLUFFS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, [1985?]. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographics Series #23. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min.audio cassette & 8 pp photocopy J-card with colour photocopy cover panel in hinged plastic box. sound poetry. the choir is composed of Dev Balkissoon, Shanti Balkissoon, Koula Bouloukos, Eika Dirsus, John Garbuio, Josh Greer, David Holmes, Joelann Irving, Cathy Kirkness, Tom McAuliffe, Phil Robson; supplemented on 3 works by Owen Sound (Dean, Steven Smith, Richard Truhlar). includes versions of Robert Ashley’s She Was A Visitor & Truhlar’s Glass On The Beach.

SHIKATANI (Gerry) THE BOOK OF TREE: a cottage journal. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, september 1987. 15o #d copies. 48 pp/42 printed, offset. 8 x 8, japanese-sewn card covers. prose.

SILVERWIND (Jasmine) ” what buisness has th butter being melted, when “. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issue as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, rubberstamp. 7 x 2-1/4, leaflet. a poem.

SMITH (Jim) VIRUS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1983. 275 trade copies of an edition totalling 3oo. 32 pp/2o printed, offset. 7 x 5, stapled wrappers. prose.

SMITH (Steven [Ross])(with Richard Truhlar) from within. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1o october 1982. 2oo #d copies. 4 pp printed, photocopy. 5-1/2 x 8-1/2, leaflet. poetry, with a cover photograph by [André Kertesz]. issued in conjunction with a reading at The Abbey Bookshop, Toronto.

SOUTHWARD (Keith) WIND CHIMES. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1981. 25o copies. 36 pp/17 printed, offset. 3-15/16 x 2-1/2, stapled wrappers. poetry.

SWEDE (George) FLAKING PAINT. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, april 1983. 3oo copies. 2o pp/16 printed, offset. 5-5/8 x 3, perfectbound wrappers. poetry. cover typography by bpNichol.

TEKST (Glenn Frew, John Korcok, Richard Truhlar, Mara Zibens) AVATAMSAKA’S WAVE PACKET. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, october 198o. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographic Series #9. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min.audiocassette with 6 pp offset J-card in hinged plastic box. electronic music.

TRUHLAR (Richard) ” Dear : “. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, nd [early 198os]. 8-1/2 x 11, photocopy & rubberstamp broadside. prose open letter of rejection for the press prepared by Truhlar & used by all(?) editors.

____ GROWLING IN THE ROOFBEAMS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1984. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographic Series #1o. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 45 min.audiocassette with 8 pp photocopy J-card in hinged plastic box. sound poetry.

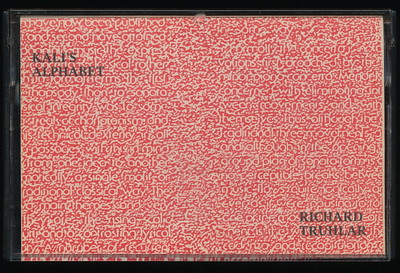

TRUHLAR (Richard) Kali’s Alphabet. Underwhich Editions, 1982. Issued as Audiographic Series #14.

UU (David) High C. Selected Sound and Visual Poems 1965-1983. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 19 august 1991. 3oo #d copies. 9o pp/8o printed, offset & silkscreen. 7 x 1o, perfectbound wrappers with 5 tipped in leaves & 2 interior labels. frontis & (invisible) restorations by jwcurry.

VALOCH (Jiri) HAIKU. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, april 1983. 3oo copies. 2o pp/9 printed, offset. 5-5/8 x 5-9/16, perfectbound wrappers. poetry.

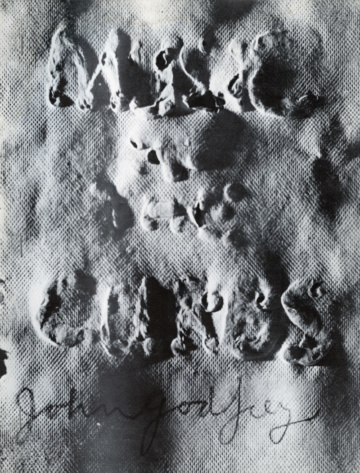

VAN DUSEN (Kate) but but. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1988. 68 pp/57 printed, offset. 5-1/4 x 8, perfectbound wrappers. poetry, with a cover sculpture by Tom Burrows.

VENRIGHT (Steve) VISITATIONS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1986. 68 pp/49 printed, offset. 5-3/8 x 7-3/4, perfectbound wrappers. prose, with 3 collages by the author. Venright’s first book.

WALDROP (Keith) WATER MARKS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, [late october] 1987. 5oo [ie 538 orso] copies. 36 pp/29 printed, offset. 5-1/2 x 5-1/2, perfectbound wrappers. poetry, with cover, halftitle, & title page lettering by bpNichol.

ZIBENS (Mara) TRANCE RESISTANCE. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, january 1986. 1oo copies issued as Audiographic Series #24. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min.audiocassette with 8pp offset J-card in hinged plastic box. music. cover frottage by Richard Truhlar.

Underwhich Editions include

AUDIOTHOLOGY 2. “Electroacoustics”. edited by Richard Truhlar. Toronto, Underwhich Ediitons, 1989. 2oo copies issued as Audiographics Series #35. 9o min.audiocassette in 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8 hinged plastic box with 12pp offset J-card. sound poetry & music. the contributors are Michael Chocholak, Misha Chocholak, “colette”, Victor Coleman, Robert Creeley, Don Daurio, Paul Dutton, Jeff Greinke, Michael Horwood, David Lee, Allan Mattes, Chris Meloche, David Myers, bpNichol, John Oswald, Randall A.Smith, Truhlar, Hildegard Westerkamp & Mara Zibens.

BARLOW (John) the space near sudbury. Toronto, Underwhich Renegade, 18 march 1995. of an edition totalling 67, 36 trade copies #d 31-66. 12 pp/6 printed, rubberstamp & photocopy. 6 x 4, sewn wrappers with flaps tipped in. a poem; cover photograph (of jwcurry in Sudbury) by Gio Sampogna.

BARRETO-RIVERA (Rafael) HERE IT HAS RAINED. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, fall 1978. 5oo copies. 2o pp/16 printed, offset. 5-1/2 x 8-7/16, stapled wrappers. prose, cover & design by Glenn Goluska.

BARWIN (Gary) ukiah poems 4. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 23 february 1988. 15o #d copies issued as 1cent #197. 4 pp/3 printed, rubberstamp & silkscreen. 4 x 6-1/4, leaflet. a poem.

BEATTY (Patricia) Form Without Formula. A Concise Guide To The Choreographic Process. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1985. 68 pp/57 printed, offset. 5-1/2 x 8-1/2, perfectbound wrappers. prose as titled, with a cover painting (detail) by William Ronald, introduction by Danny Grossman, photos by Graham Bezant & Andrew Oxenham, cartoon by Edward Koren. this first edition occurred thanks to bpNichol’s interest in the problems of notating performance instructions. it has since become a standard text & been reprinted many times.

BERTRAND (Denise) KHRONIKA. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1984. 25o #d copies. 24 pp/12 printed, offset. 4-9/16 x 7-151/16, stapled wrappers in loose-fitting dj. prose.

BROCK (Randall) ” deep “. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, photocopy & rubberstamp. 4-1/4 x 5-1/4, leaflet. a poem.

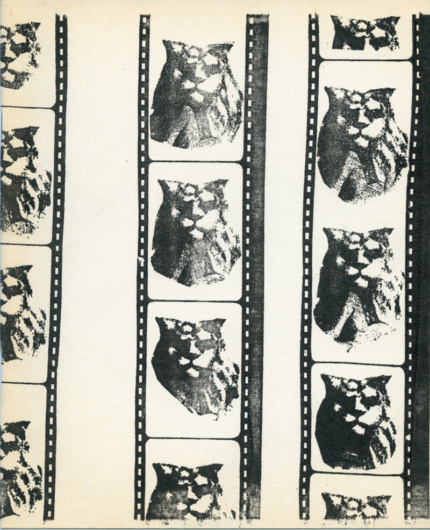

CHOCHOLAK (Michael) OWL MAN DREAMS. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, september 1986. 1oo #d copies issued as Audiographics #29. 4-1/4 x 2-3/4 x 5/8, 6o min.audiocassette with 8-panel offset J-card in hinged plastic case. music.

CLARK (Thomas A) ON GRETA BRIDGE. Nailsworth (England) & Toronto, Moscharel Press & Underwhich Editions, 1984. 5oo copies. 12 pp/8 printed, offset. 5 x 6, stapled wrappers. prose.

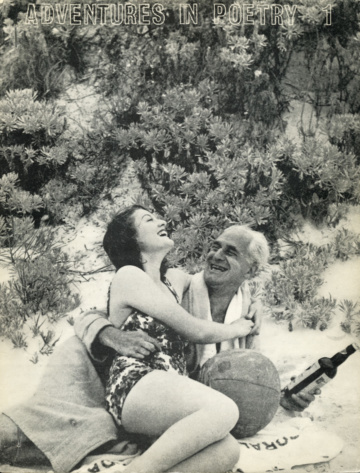

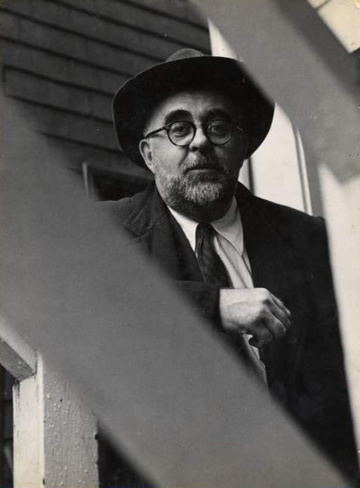

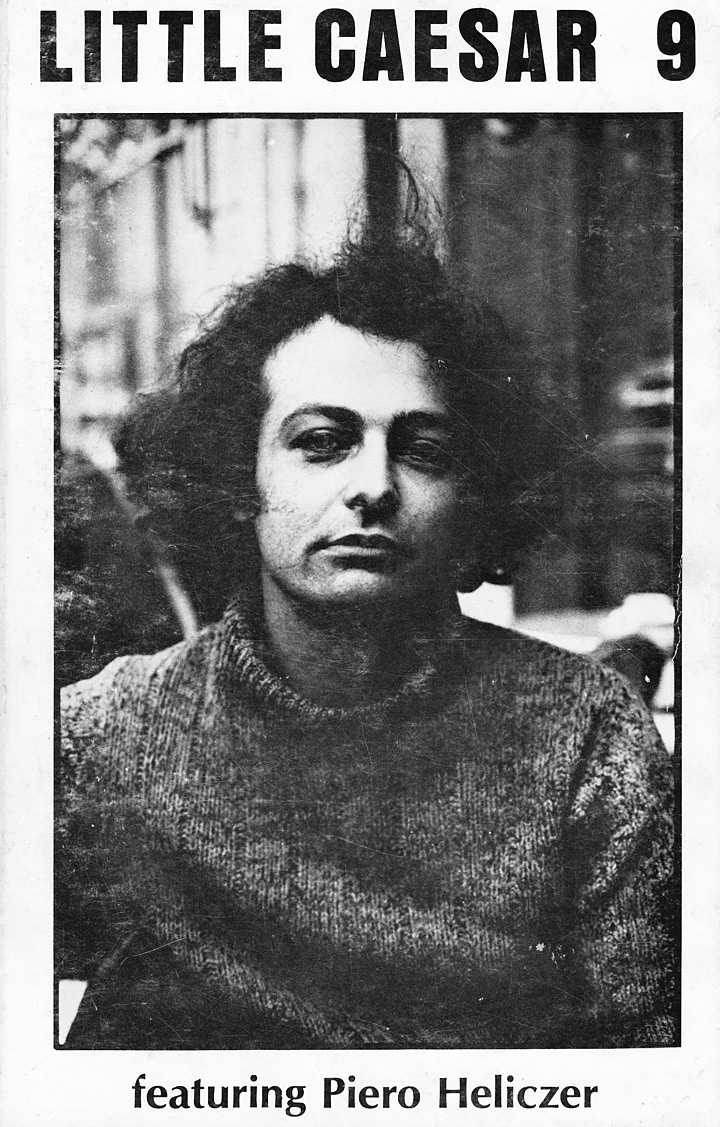

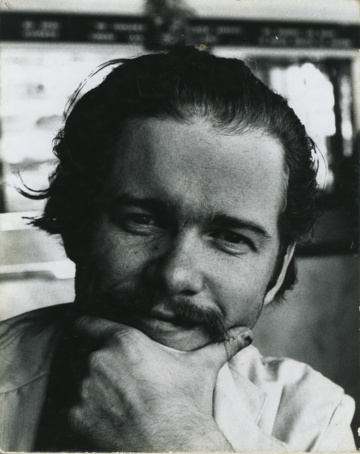

COBBING (Bob) Ballet of the Speech Organs: Bob Cobbing On Bob Cobbing. as interviewed by Steven Ross Smith. Saskatoon & Toronto, Underwhich Editions,1998. 15o #d copies. 48 pp/41 printed, offset. 5-3/8 x 8-1/2, stapled wrappers. with an introduction by Smith, 9 sound texts by Cobbing (dating back to 1942!), & 5 uncredited photographs, including one of bpNichol toasting Cobbing in Toronto in 1986 (Stephen Scobie in fuzzy foreground?).

COLEMAN (Victor) FROM THE DARK WOOD. Poems 1977-83. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 18 december 1985. of an edition totalling 526, 5oo trade copies, 1/26 copies #d & signed. 4o pp/3o printed, offset. 8-1/4 x 1o-3/4, stapled wrappers. with cover & 3 interior illustrations by Robert Fones.

CURRY (jw) 2 attentions. [2nd edition, revised, of dear diary revised attentions. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, for 3 july 1985. approx.21o copies issued for inclusion in Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp printed, rubberstamp in photocopy covers. 4-3/8 x 5-1/4, leaflet. a severe reduction of curry’s 2nd collection of poetry.

____(with Peggy Lefler) Logical Sequence 1o. [3rd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 21o copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, photocopy in rubberstamp cover. 5-1/2 x 2-1/4, leaflet. a concrete poem. 1st released as a leaflet by Curvd H&Z (198o), subsequently included as a broadside in Lefler’s Different Tenses (Curvd H&z, 198o).

DEAHL (James) LISTENING TO TAKEMITSU AFTER A DEATH IN THE FAMILY. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, [1987]. 174 trade copies of an edition totalling 2oo. 6 pp printed, offset. 4-5/8 x 8-1/2, leaflet. poetry.

DEAN (Michael) HEADS & H&Z. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, for 3 july 1985. 2oo #d copies issued for inclusion in Heads & H&z, an overrun of un#d copies not released. 8 pp/4 printed, offset in silkscreen cover with rubberstamp addition to last page. 8-1/2 x 11, 4 leaves grommetted at corner. prose introduction to the anthology by Dean with letter in response by jwcurry & his title page design & typography.

DEDORA (Brian) he moved. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1979. 28 pp, all except endleaves printed offset rectos only. 1o-1/2 x 7, stapled wrappers. a poem in translations [Erse by John Doyle, Ukrainian by Marco Carynnyk] that switch sides of the page as the sequence progresses, the english coming from between as they cross over each other. an elegant poem & concrete sequencing & one of the 1st batch of Underwhich titles.

DUDLEY (Michael) ” the heat… “. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 21o copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, rubberstamp with perforated ellipsis p.3. 4-5/16 x 1-15/16, leaflet. a poem.

DUTTON (Paul) ” BROWSE “. [Toronto], Underwhich Editions, [199-?]. 8-1/2 x 5-1/2, laser broadside. a flier made primarily as a handout at bookfairs.

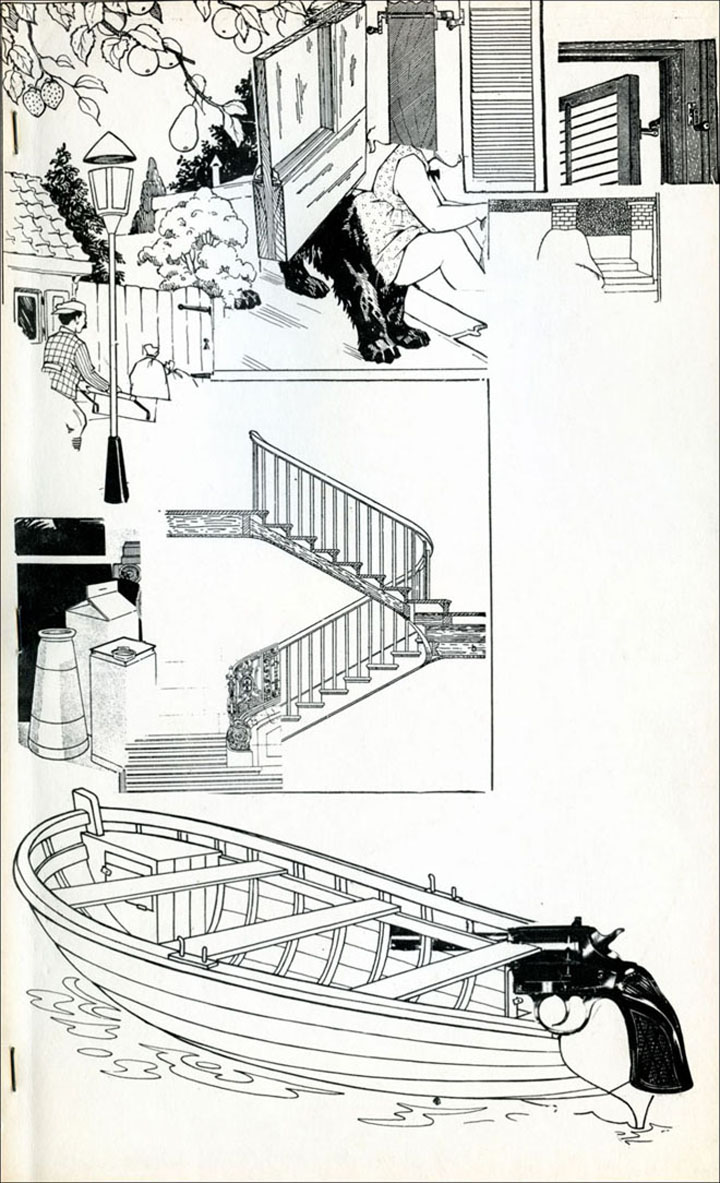

FENCOTT (Clive) NON HYSTERON PROTERON. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, summer 1984. 5oo copies. 5-1/2 x 8-1/4, perfectbound wrappers. a visual novel.

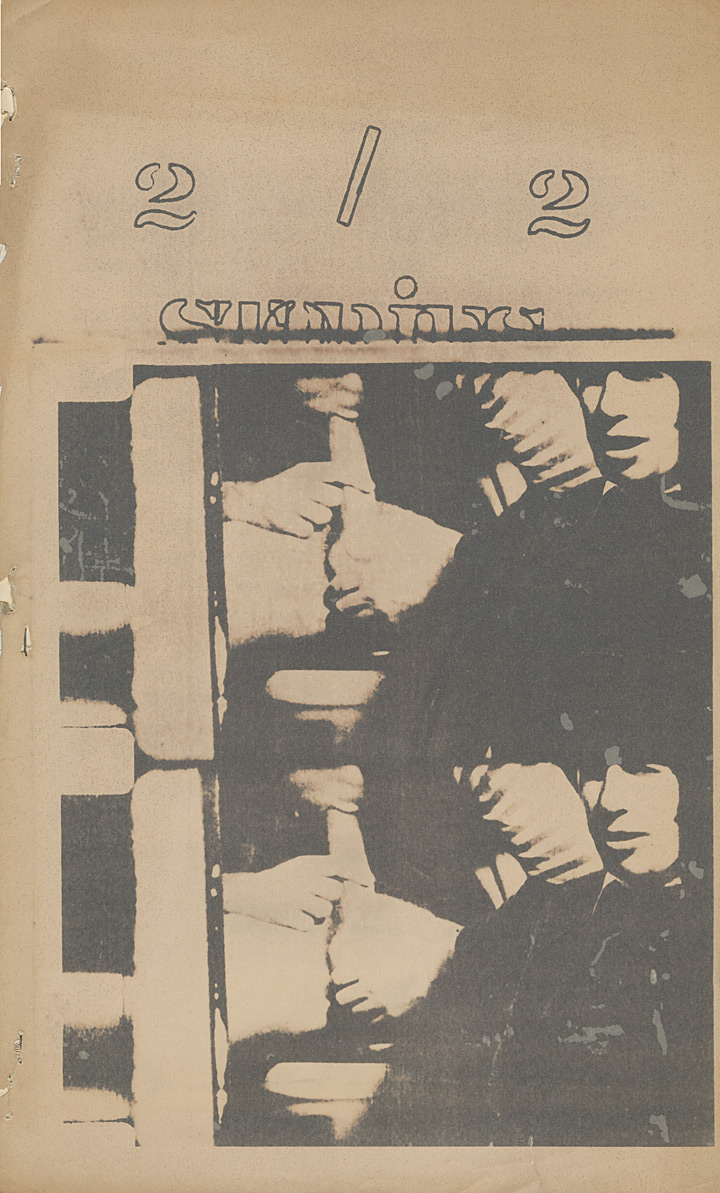

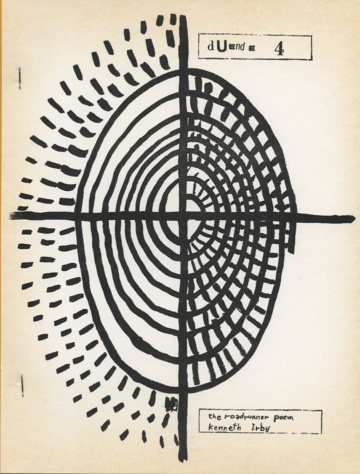

FIVE ON FICHE. Prose and poetry. edited by Richard Truhlar. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 198o. [25o copies?] issued as Microfiche Series #1. 5-13/16 x 4-1/8, photographic acetate broadside in 6 x 4-1/8 pocket printed offset recto only. the contributors are Michael Dean, Brian Dedora, John Riddell, Steven Smith & Truhlar. anyone with an old ‘fiche reader stashed in their walk-in closet? excited by the low cost of production of a single microprint acetate rather than an 84pp book, Truhlar plotted a series of such anthologies (it was to’ve been followed by Langscapes, an anthology of concrete/visual poetry coëdited by Riddell) but the idea petered out in the face of sparse orders: if people were going to have to go to a library to read it, let the library order it (few did).

FOUR HORSEMEN. Bootleg. Underwhich Editions, 1981.

FRATICELLI (Marco) ” Lights in the distance – “. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, rubberstamp. 4-1/4 x 3-1/2, leaflet. a poem.

FREW (Glenn) full circle. A performance for two male voices with cultured British accents. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1983. 1oo #d copies; this copy out of series, not #d. 24 pp/18 printed, offset. 8 x 5, stapled wrappers.

GARNER (Don) ROACHES. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/3 printed, photocopy. 2 x 3-1/4, leaflet. a poem. anonymous wraparound cover collage by jwcurry.

GILBERT (Gerry) year of the rush. Saskatoon & Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 1994. 78 pp/73 printed, offset. 5-1/2 x 8-3/4, perfectbound wrappers. poetry & prose, with cover photo by Majka Miozga.

GORMAN (LeRoy) Whose Smile The Ripple Warps. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 198o. 3oo copies. 2o pp/16 printed, offset. 5-3/4 x 5-3/4, perfectbound wrappers. visual poetry.

GRACE (Susan Andrews) WEARING MY FATHER. Saskatoon, Underwhich Editions, july 199o. 2oo #d copies. 24 pp/16 printed, offset. 5-1/4 x 4-1/4, sewn wrappers. poetry.

GUNNARS (Kristjana) water, waiting. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 17 june 1987. 15o #d copies. 12 pp/8 printed, offset with silkscreen cover graphic by jwcurry. 5-1/2 x 7, sewn wrappers. poetry.

HANSON (R.D) Cafeteria Scriptures. [2nd edition. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo+ copies issued as part of Heads & H&z; not released separately]. 4 pp/2 printed, photocopy. 4-1/4 x 5-1/2, leaflet. a poem.

HEADS & H&Z. edited by jwcurry & Michael Dean. Toronto, Underwhich Editions, 3 july 1985. 2oo unique copies #d & signed by the editors. 36o pp/213 printed, photocopy, rubberstamp, offset, silkscreen, typescript & holograph. 9 x 11-1/2 x 1-1/2, 68 leaves, leaflets, envelopes & variously-bound pamphlets in box with separate lid & cover label (some copies have an interior ISBN label). primarily, poetry, concrete poetry & graphics, a collection of reïssues of early Curvd H&z publications (march 1979–april 1982), many in revised formats. contributors include Gregg Andely, David Aylward, Dave Beach, Brian Dedora, Don Garner, R.D.Hanson, Mark Laba, Peggy Lefler, Steve McCaffery, Bonnie McDowell, bpNichol, Jasmine Silverwind & David UU, among many others. approximately a third of the copies were destroyed in a flood while in storage.

(cont’d left)

Myrna Lefler. stones. Underwhich Editions, 1985. 2nd edition.

Richard Truhlar. Kali’s Alphabet. Underwhich Editions, 1982. Issued as Audiographic Series 14.

Scarborough Sound Symphony, conducted by Michael Dean. Scarborough Bluffs. Underwhich Editions, [1985?]. Issued as Audiographics Series #23.

jwcurry & Michael Dean, eds. Heads & H&z. Underwhich Editions, 1985.

Arnold Itwaru. The Sacred Presence (my father, my mother, long dead). Underwhich Editions, 1986.

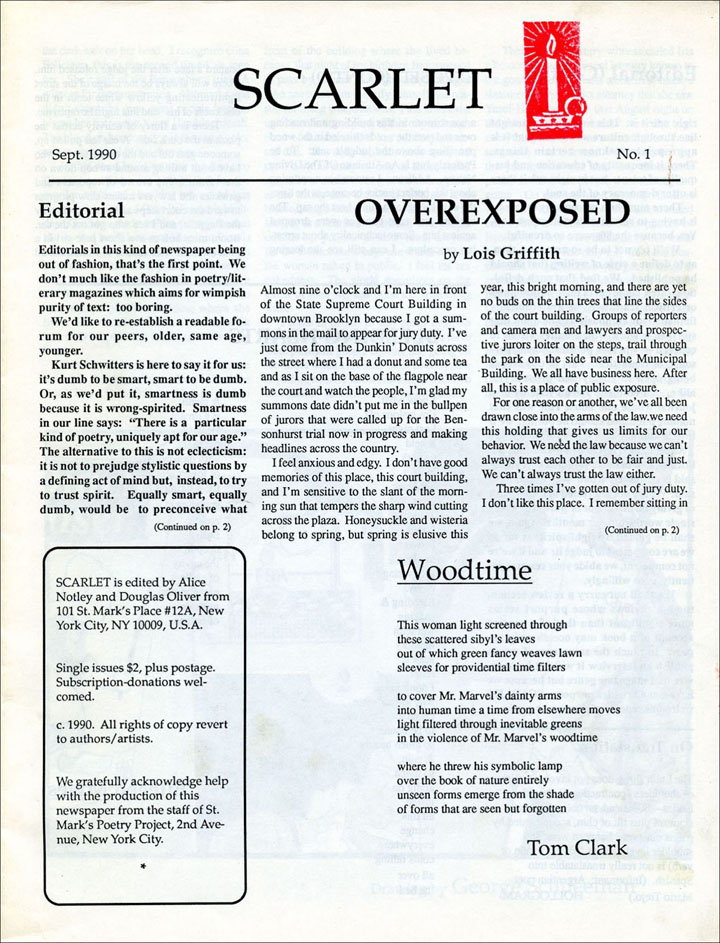

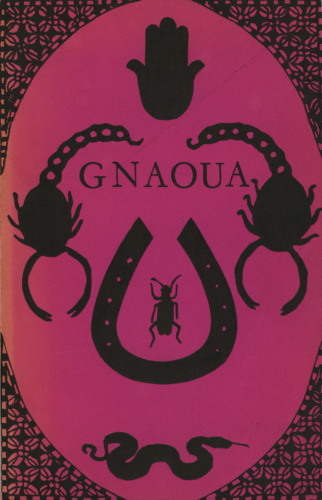

![Panama Rose [Rosalind Schwartz], The Hashish Cookbook (1966).](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/panama-rose-hashish-cookbook-gnaoua-press-1966-r-385x530.jpg)

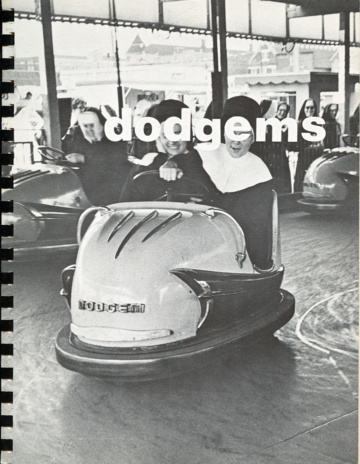

![Dodgems [2], 1979.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/eileen-myles-dodgems-2-1977-r-412x530.jpg)

![The World 39 [1983?].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-world-no-39-1983-r-360x467.jpg)

![Flyer for a reading by Anne Waldman and Kenward Elmslie at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, May 28, [1969].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/flyer-anne-waldman-kenward-elmslie-r-402x530.jpg)

![Flyer for a reading by Larry Goodell and Stephen Rodefer at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, September 26, [no year].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/goodell-rodefer-poetry-project-reading-r-2-360x465.jpg)

![Detroit Artists Workshop Benefit: Seven Poets, Santa Fe-Albuquerque. Captain Mimeo and the Pepsi Shooter Press Book no. 1. [Duende Press], March 11, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/detroit-family-r-407x530.jpg)

![Wolf Vostell, and Dick Higgins, eds. Fantastic Architecture [1970 or 1971]. Book jacket illustration: Richard Hamilton’s Guggenheim Collage, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vostell-architecture-r-360x498.jpg)

![Maps 1 [1966]. Cover: Herbert Bayer, “Graphic Fragment #2.”](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/maps-1-r-599x530.jpg)

![Maps 3 [1970]: Poems for John Coltrane. Cover by Roger Shimomura.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/MAPS-no-3-1970-r-455x530.jpg)

![Charles Olson, Mayan Letters (1953 [i.e., 1954].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/charles-olson-mayan-letters-divers-press-r-409x530.jpg)

![The Floating Bear 28 [December] 1963. Cover by Alfred Leslie.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/4the-floating-bear_1963_28-405x530.jpg)

![Floating Bear 37 [March–July] 1969. Cover by Wallace Berman.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-floating-bear_1969_37-1-r-410x530.jpg)

![Jess [Collins], Christian Morgenstern’s Gallowsongs (1970). Illustrations and versions by Jess.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/jess-gallowsongs-black-sparrow-1970-r-400x530.jpg)