Gare du Nord

Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver

Paris

Five issues from 1997–1999, including vol. 1, nos. 1–vol. 2, no. 2.

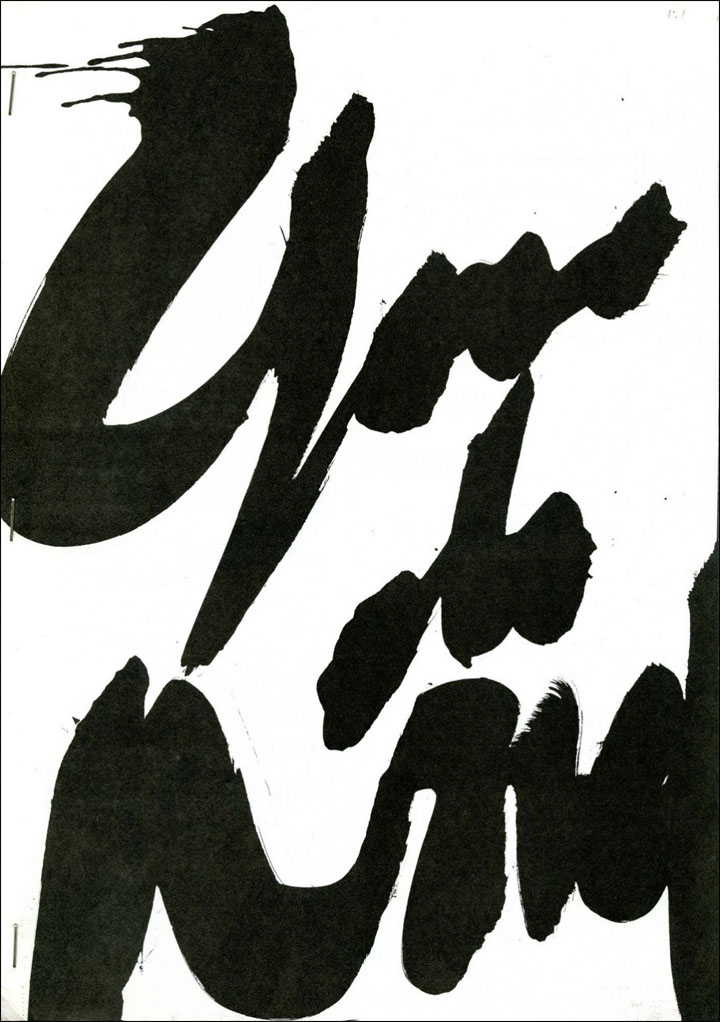

Gare du Nord, vol. 1, no. 1. 1997.

A “magazine of poetry and opinion from Paris” that would fill a gap between more well-known print magazines and the rise of online literary journals, Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver began publishing Gare du Nord five years after the final issue of their first co-edited magazine Scarlet. Named after the famous train station near their apartment, where the couple had lived since 1992, Gare du Nord extends the “right spirit” of Scarlet by publishing writers such as Etel Adnan, Edwin Denby, Joanne Kyger, and Renee Gladman as well as artwork by Jane Dalrymple-Hollo, Rudy Burckhardt, George Schneeman, Yvonne Jacquette, and William Yackulic. As Notley and Oliver write in the editorial in the first issue:

Since Britain, the U.S. and France travel to us here beside the Gare du Nord, we’ll do our best to act as a rail-crossing point, providing a good mix of work from as many different cultures as we can find, with a proper balance of gender (of course) and genre (less obvious). Easily bored, we’d like to be bratty and funny, as well as serious. Easily put off by the merely shallow, we’d like to present the linguistically complex too.

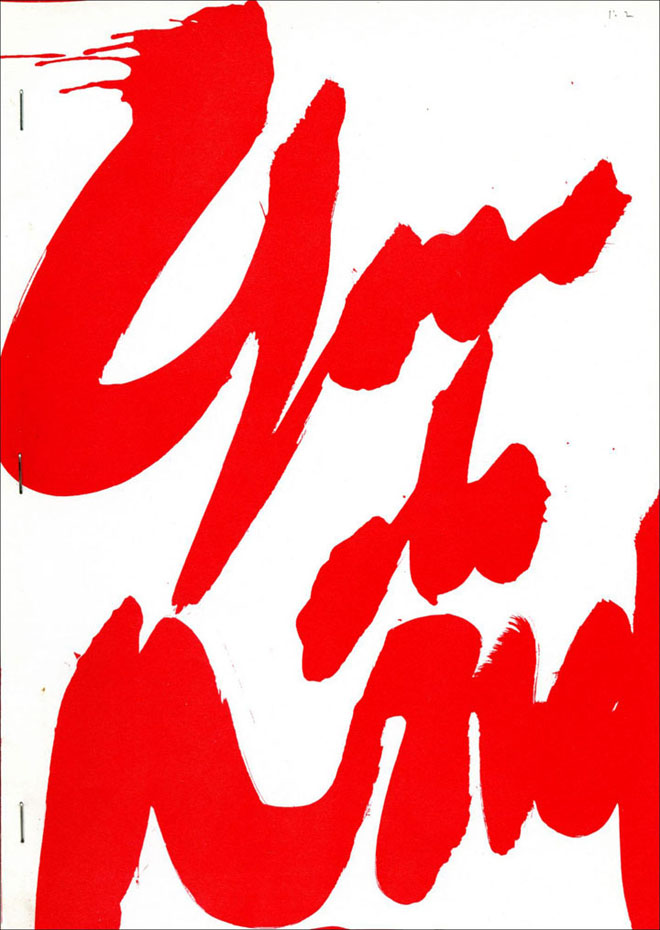

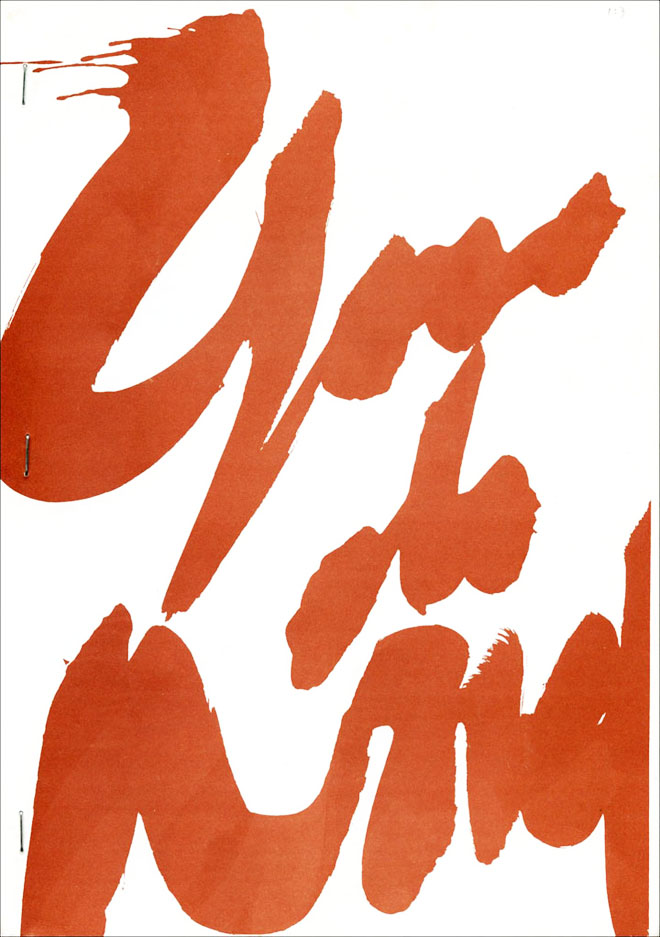

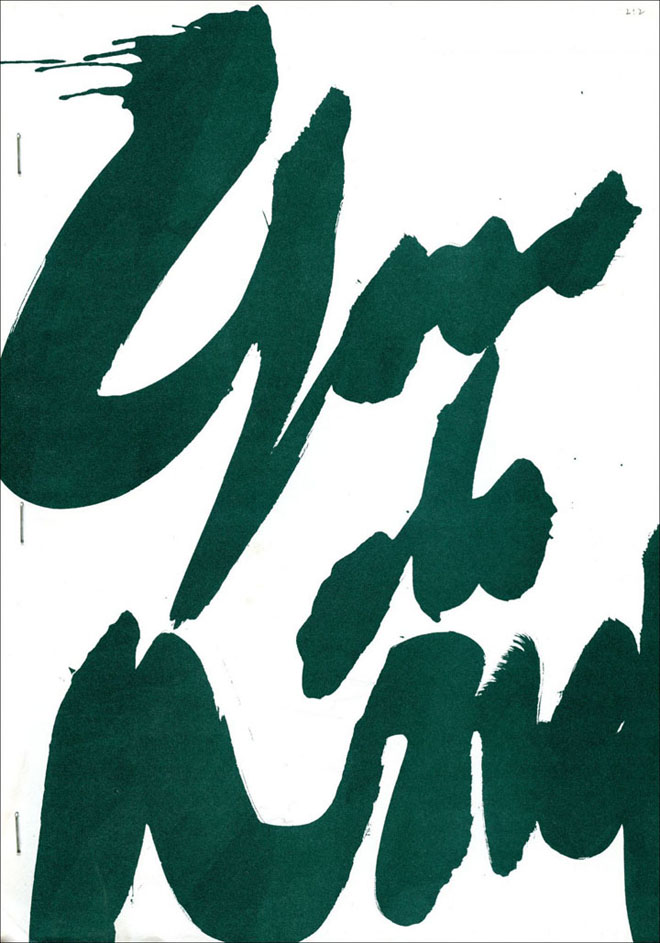

Appearing in five issues, each side-stapled with a cover by Laurent Baude, Gare du Nord combines the design capabilities of desktop publishing with the material aesthetics of the little magazines of the 1960s and ‘70s. As Notley describes, “Doug wanted our magazine to have production values. [He] had journalist experience and so he wanted to do these beautiful magazines although we still stapled them.”

Also like Scarlet, the design and editing of Gare du Nord lends itself to conversation, experimentation, and a gathering of communities. Serial features such as Notley’s “Cosmic Chat” written in the style of Disobedience, a reader inquiry feature designed by Oliver, an ongoing “Books We’re Reading” list, and a series of “chats” between Notley and Oliver as the interlocutors “X” and “Y” about topics like syntax, chauvinism, tone, and politics make Gare du Nord a rich, complex window into the intellectual and imaginative world of Notley and Oliver’s shared life in Paris. A stance described by “X” in the magazine’s final issue embodies Notley and Oliver’s shared vision and disobedience:

I want to say one more thing which is that human societies and politics are tremendously various, and they go from areas that can only be discussed in the mode of high intelligence to areas that can only be discussed from the viewpoint of this immense emotional response that you’re talking about to areas that can also be discussed with humour and generosity, which we’ve also mentioned. And why the hell we don’t understand that poetry must have all those aspects, I don’t know. And I despair, because you cannot mention this, you cannot proclaim this without people looking at you as though you’re saying something unwelcome and irrelevant.

In a 1997 interview, Notley describes the deeply collaborative aspect of the magazine:

At the moment I work most in conjunction with Doug. We’re interested in the same kinds of forms and share so many of the same concerns, but speak so differently from each other, being American and English, that we’re enriched by the different textures of our languages. And also the differing textures of the ways in which we think. I also always want to know what people like Ron Padgett, Lorenzo Thomas, Anne Waldman, Anselm Hollo, etc. think about things. I continue to be interested in the work of Leslie Scalapino, Eileen Myles, Joanne Kyger, Lyn Hejinian. I want to know how mature minds are dealing with what’s going on in the world. And I’m waiting to see what the very young will come up with in terms of forms and techniques.

— Nick Sturm, Atlanta, May 2021

Gare du Nord, vol. 1, no. 2. 1998.

Gare du Nord, vol. 1, no. 3. 1998.

Gare du Nord, vol 2. no. 1. 1998.

Gare du Nord, vol. 2, no. 2. 1999.