Women’s and Feminist Writing

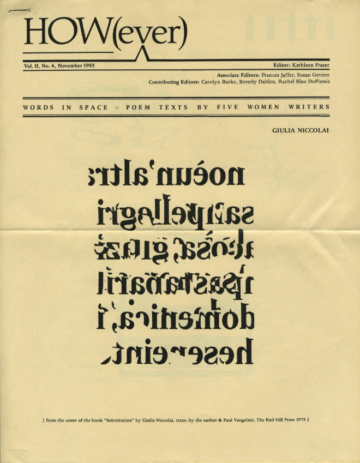

Great strides were made in the development of women’s and feminist writing during the late ’60s and through the ’70s. Ron Silliman observed in 1982 that “the single most significant change in American poetry over the past two decades is to be seen in the central role of writing within feminist culture, which in 1982 is (for good reason) the largest of all possible verse audiences.” [11] Important developments among women and feminist poets run parallel to the New American Poetry but rarely intersect during the 1960–1980 period, except perhaps as they relate to the creation of independent poet-operated women’s presses. The establishment, for example, of Judy Grahn’s Women’s Press Collective in Oakland in 1969 and Alta’s Shameless Hussy Press in Berkeley were crucial in providing a venue for women’s literary voices to speak out. These writers (with significant exceptions) felt self-consciously apart from the more experimental side of poetry and determined that their concerns might perhaps be more directly served through populist modes of expression. The example of work by such writers as Adrienne Rich, Judy Grahn, Pat Parker, Ntozake Shange, and Susan Griffin, among many others, was important in defining and foregrounding issues particular to women and feminists that would be further explored over the next two decades. It is no coincidence that the magazine HOW(ever), edited by Kathleen Fraser and first published in May 1983, opens with the questioning “And what about the women who were writing experimentally? Oh, were there women poets writing experimentally? Yes there were, they were.” Fraser, working with contributing editors Frances Jaffer, Beverly Dahlen, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and Carolyn Burke (and later with Susan Gevirtz, Chris Tysh, Myung Mi Kim, Meredith Strieker, Diane Glancy, and Adalaide Morris), published sixteen issues (in six volumes) between 1983 and 1992. Unlike many other feminist magazines, HOW(ever) was framed in a literary context and traced its history to include Emily Dickinson, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, and Dorothy Richardson. Thus, HOW(ever) set out to be, as Jaffer expressed it in the first issue, “A vehicle for experimentalist poetry—post-modern if you will, to be thought of seriously as an appropriate poetry for women and feminists.” Contributors and topics include Norma Cole, Karen Riley, Kathy Acker on humility, Lyn Hejinian, Caroline Burke on Mina Loy, Johanna Drucker on canon formation, a group of writings on Barbara Guest, Laura Moriarty, Joan Retallack, Gail Scott, and the various editors, among many others.

African American Writing

African American literary magazines of the years 1960–1980 were rarely devoted exclusively to literary concerns—more often they presented a mix of cultural expression and political commentary in an ongoing effort to battle the racism, oppression, and violence that characterized the era. The history of the African American little magazine runs rich and deep, and a beginning look would include such publications as Freelance, Confrontation, Callaloo, Soulbook, Umbra, the Journal of Black Poetry, and Hambone, among many others. As with feminist writing, third-world writing, and writing by people of color in general, the trajectory of African American poetry charts a somewhat different course than that of the New American Poetry and nearly always speaks to its own audience of its own issues and on its own terms.

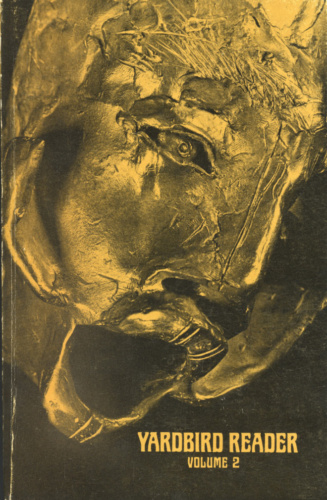

Yardbird Reader, vol. 2 (1973).

One fascinating and eclectic example is Yardbird Reader. Edited by Ishmael Reed, Al Young, Shawn Wong, Frank Chin, and William Lawson, it ran for five volumes, from 1972 to 1976. A vast range of writing from many cultures was presented, including African Americans, Asian Americans, Colombians, Puerto Ricans, Filipino-Americans, Franco-Americans, Anglo-Americans, North Africans, Kenyans, and Caribbeans. Y’Bird, edited by Ishmael Reed, continued the work after the demise of Yardbird Reader. In 1978, Grove Press published a collection of work from Yardbird Reader entitled Yardbird Lives! Dudley Randall’s Broadside Press in Detroit was a prominent venue for the Black Arts Movement, and during the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s published such writers as June Jordan, Lucille Clifton, Raymond Patterson, Etheridge Knight, Audre Lorde, Dudley Randall, Alice Walker, and Sonia Sanchez, among many others. LeRoi Jones and Larry Neal edited the provocative Black Fire: Anthology of Afro-American Writing, published in 1968.

Citation:

11. Ron Silliman, ed., “Language Writing,” Ironwood 20 [vol. 10, no. 2] (Fall 1982): p. 68.