Tuumba Press

Lyn Hejinian

Willits and Berkeley, California

1976–1984

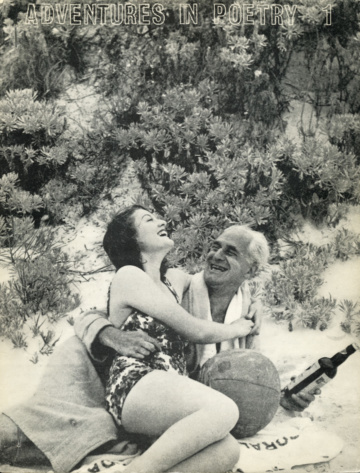

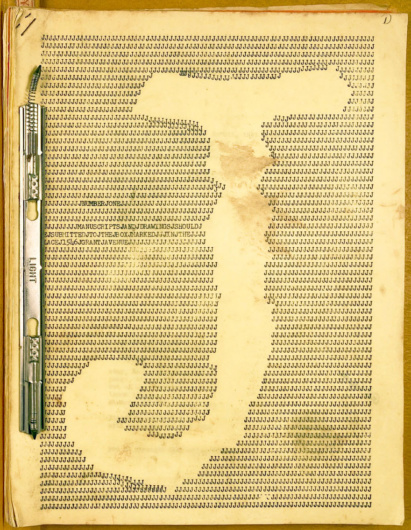

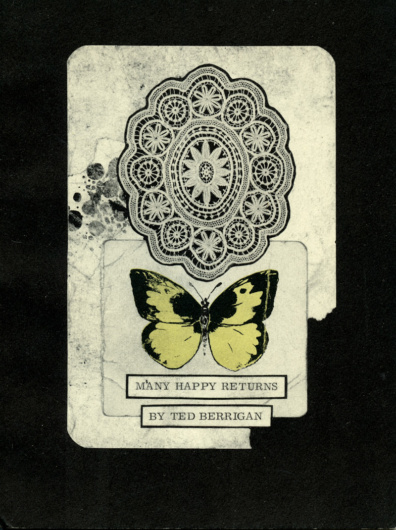

Carla Harryman, Percentage (1979).

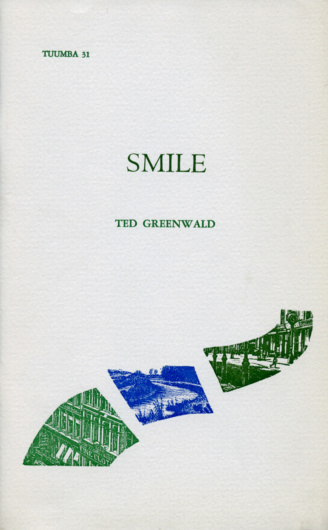

I founded Tuumba Press in 1976. It was a solo venture in that I had no partner(s) or assistant(s) but it was not a private or solitary one; I had come to realize that poetry exists not in isolation (alone on its lonely page) but in transit, as experience, in the social worlds of people. For poetry to exist, it has to be given meaning, and for meaning to develop there must be communities of people thinking about it. Publishing books as I did was a way of contributing to such a community—even a way of helping to invent it. Invention is essential to every aspect of a life of writing. In order to learn how to print, I invented a job for myself in the shop of a local printer. The shop was in Willits, California—a small rural town with an economy based on cattle ranching and logging; the owner of the shop (the printer, Jim Case) was adamant that “printing ain’t for girls,” but he took me on three afternoons a week as the shop’s cleaning lady. A year later I moved to Berkeley, and purchased an old Chandler-Price press from a newspaper ad. I knew how to run the press but not much about typesetting; friends (particularly Johanna Drucker and Kathy Walkup) taught me a few essentials and a number of tricks. The first eleven chapbooks (printed in Willits in 1976–77) had a slightly larger trim size than those I did myself (in a back room of the house in Berkeley)—I was using leftover paper in Willits, but in Berkeley I bought paper from a local warehouse and used the trim size that was the most economical (creating the least amount of scrap).

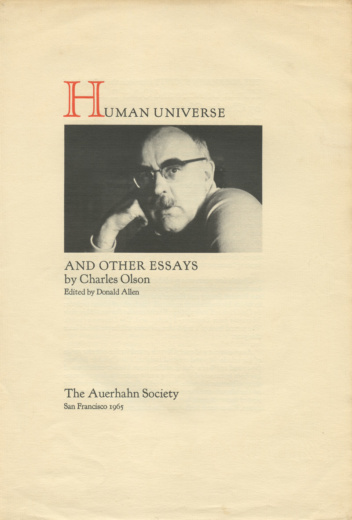

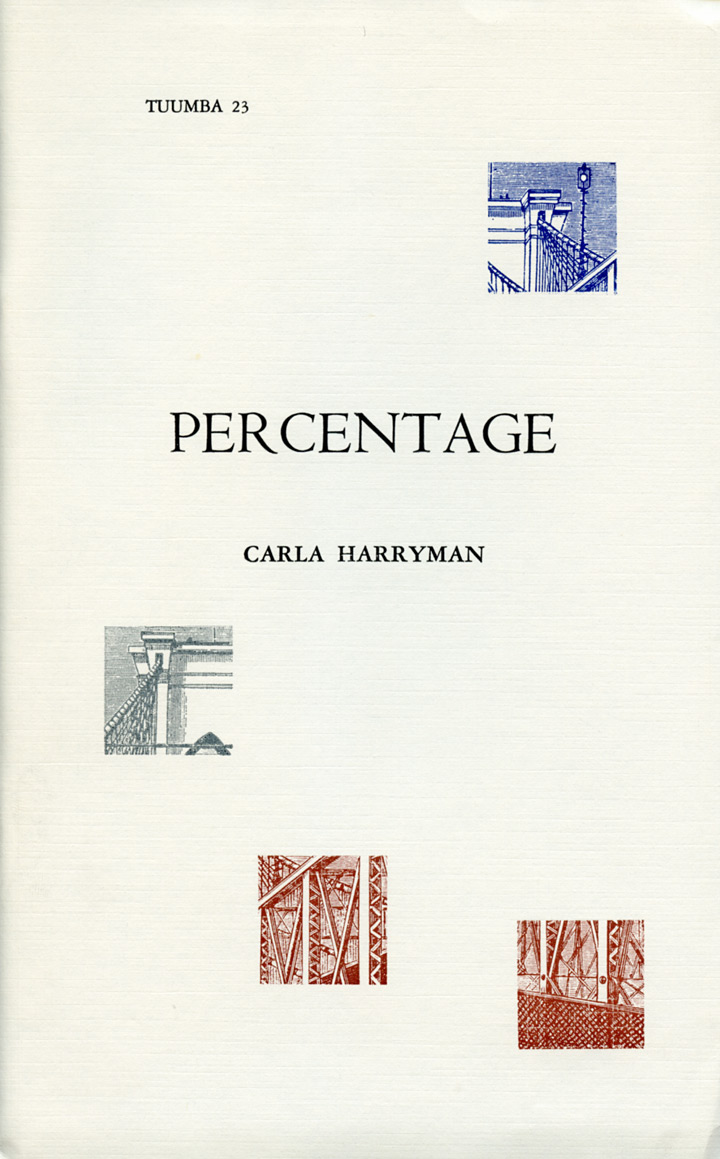

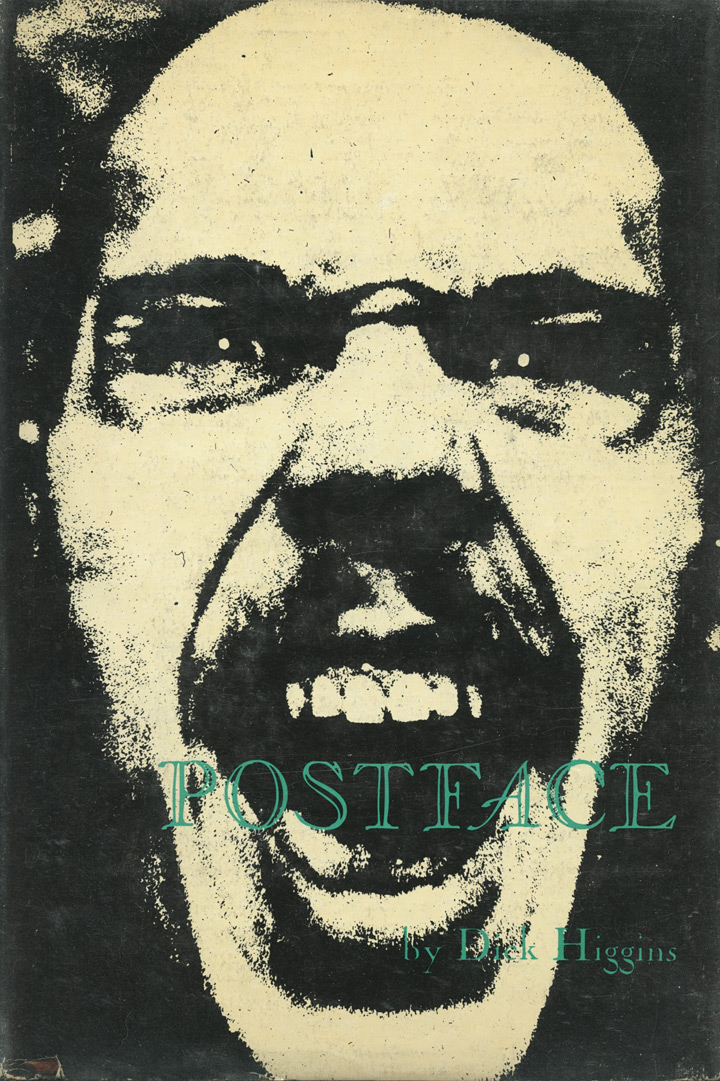

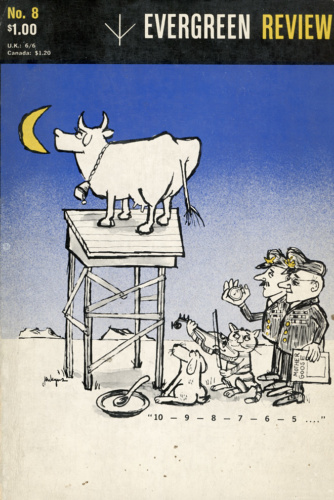

Dick Higgins, Cat Alley: A Long Short Novel (1976). Tuumba 5.

The list of authors of the first books makes it clear that for the first year and a half I was looking to various modes of “experimental,” “innovative,” or “avant-garde” writing for information; the subsequent chapbooks represent a commitment to a particular community—the group of writers who came to be associated with “Language Writing.” The chapbook format appealed to me for obvious practical reasons—a shorter book meant less work (and expense) than a longer one. But there were two other advantages to the chapbook. First, most of the books I published were commissioned—I invited poets to give me a manuscript by a certain date (usually six months to a year away)—and I didn’t want to make the invitation a burden. And second, I wanted the Tuumba books to come to people in the mode of “news”—in this sense, rather than “chapbook” perhaps one should say “pamphlet.” It is for this reason, by the way, that I didn’t handsew the books; they are all stapled—a transgression in the world of fine printing but highly practical in the world of pamphleteering.

— Lyn Hejinian, Berkeley, California, September 1997

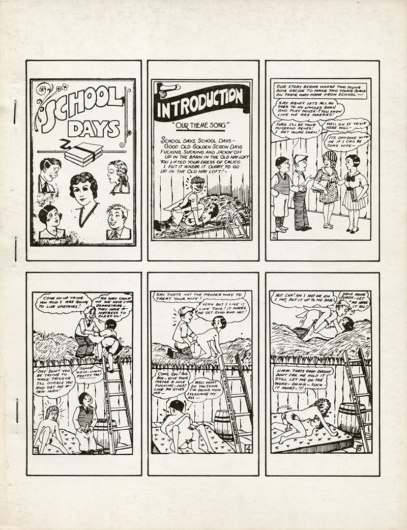

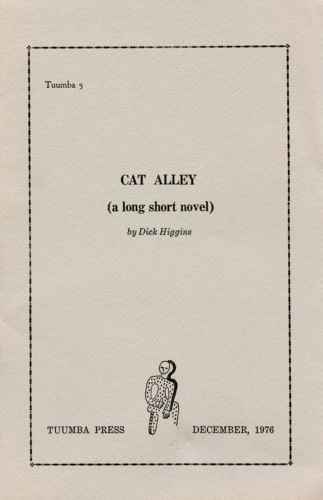

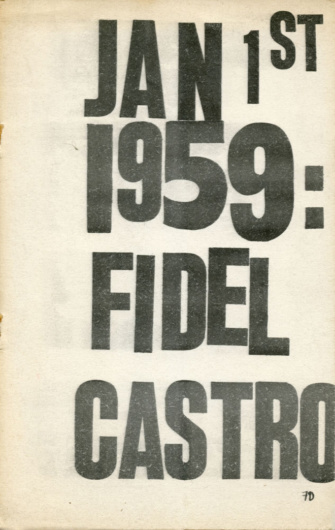

Ted Greenwald, Smile (1981). Tuumba 31.

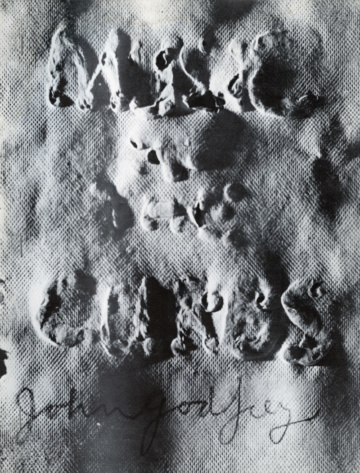

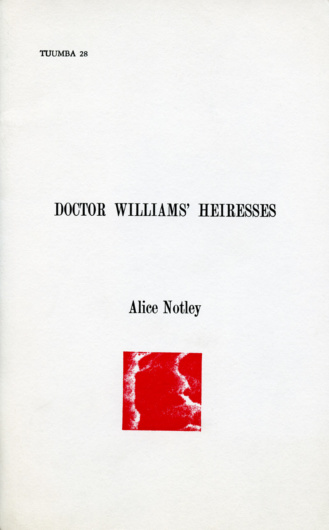

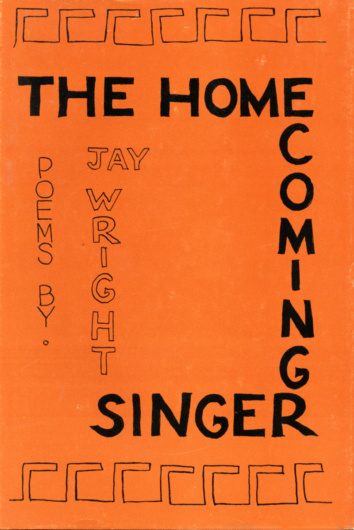

Alice Notley, Doctor Williams’ Heiresses (1980). Tuumba 28.

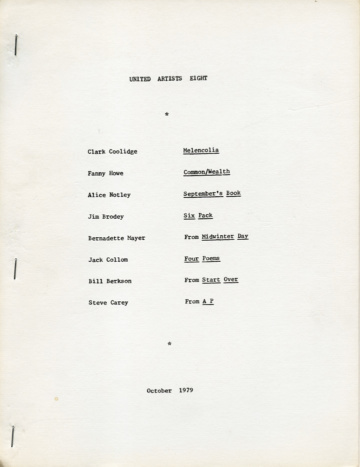

Tuumba publications

Tuumba issued fifty pamphlets and a poster. In addition the press issued numerous small broadsides, cards, and other ephemera.

What follows is a complete checklist of the pamphlets and poster:

Andrews, Bruce. Praxis. 1978. Tuumba 18.

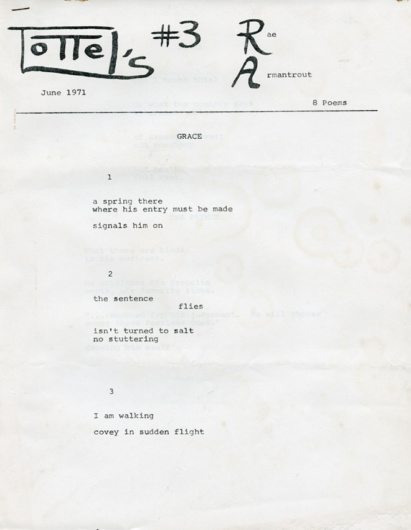

Armantrout, Rae. The Invention of Hunger. 1979. Tuumba 22.

Baracks, Barbara. No Sleep. 1977. Tuumba 11.

Benson, Steve. The Busses. 1981. Tuumba 32.

Bernheimer, Alan. State Lounge. 1981. Tuumba 33.

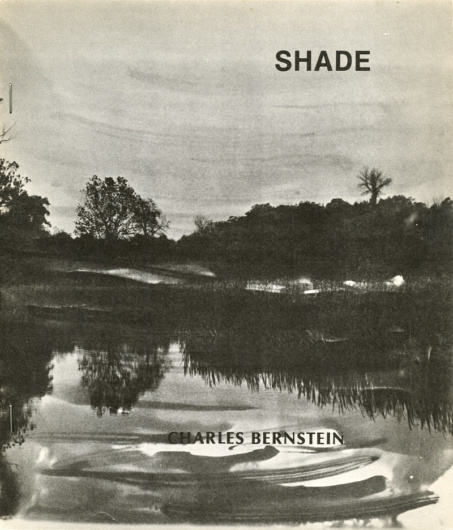

Bernstein, Charles. Senses of Responsibility. 1979. Tuumba 20.

Bromige, David. P-E-A-C-E. 1981. Tuumba 34.

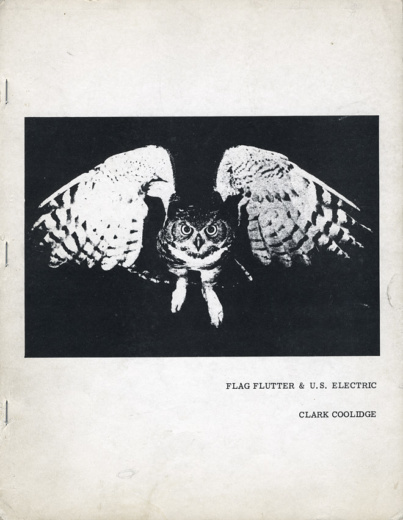

Coolidge, Clark. Research. 1982. Tuumba 40.

Day, Jean. Linear C. 1983. Tuumba 43.

DiPalma, Ray. Observatory Gardens. 1979. Tuumba 24.

Dreyer, Lynne. Step Work. 1983. Tuumba 44.

Eigner, Larry. Flat and Round. 1980. Tuumba 25.

Eisenberg, Barry. Bones’ Fire. 1977. Tuumba 7.

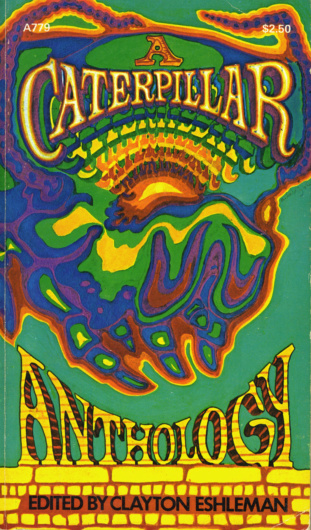

Eshleman, Clayton. The Gospel of Celine Arnauld. 1977. Tuumba 12.

Faville, Curtis. Wittgenstein’s Door. 1980. Tuumba 29.

Fraser, Kathleen. Magritte Series. 1977. Tuumba 6.

Greenwald, Ted. Smile. 1981. Tuumba 31.

Grenier, Robert. Cambridge M’ass. 1979. Poster.

Grenier, Robert. Oakland. 1980. Tuumba 27.

Hall, Doug. Beyond the Edge. 1977. Tuumba 8.

Harryman, Carla. Percentage. 1979. Tuumba 23.

Harryman, Carla. Property. 1982. Tuumba 39.

Hejinian, Lyn. Gesualdo. 1978. Tuumba 15.

Hejinian, Lyn. The Guard. 1984. Tuumba 50.

Hejinian, Lyn. A Thought Is the Bride of What Thinking. 1976. Tuumba 1.

Higgins, Dick. Cat Alley: A Long Short Novel. 1976. Tuumba 5.

Howe, Fanny. For Erato: The Meaning of Life. 1984. Tuumba 48.

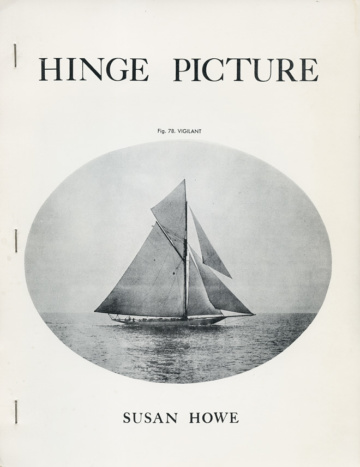

Howe, Susan. The Western Borders. 1976. Tuumba 2.

Inman, P. Ocker. 1982. Tuumba 37.

Irby, Kenneth. Archipelago. 1976. Tuumba 4.

Kahn, Paul. January. 1978. Tuumba 13.

Kostelanetz, Richard. Foreshortenings, and Other Stories. 1978. Tuumba 14.

Lipp, Jeremy. Sections from Defiled by Water. 1976. Tuumba 3.

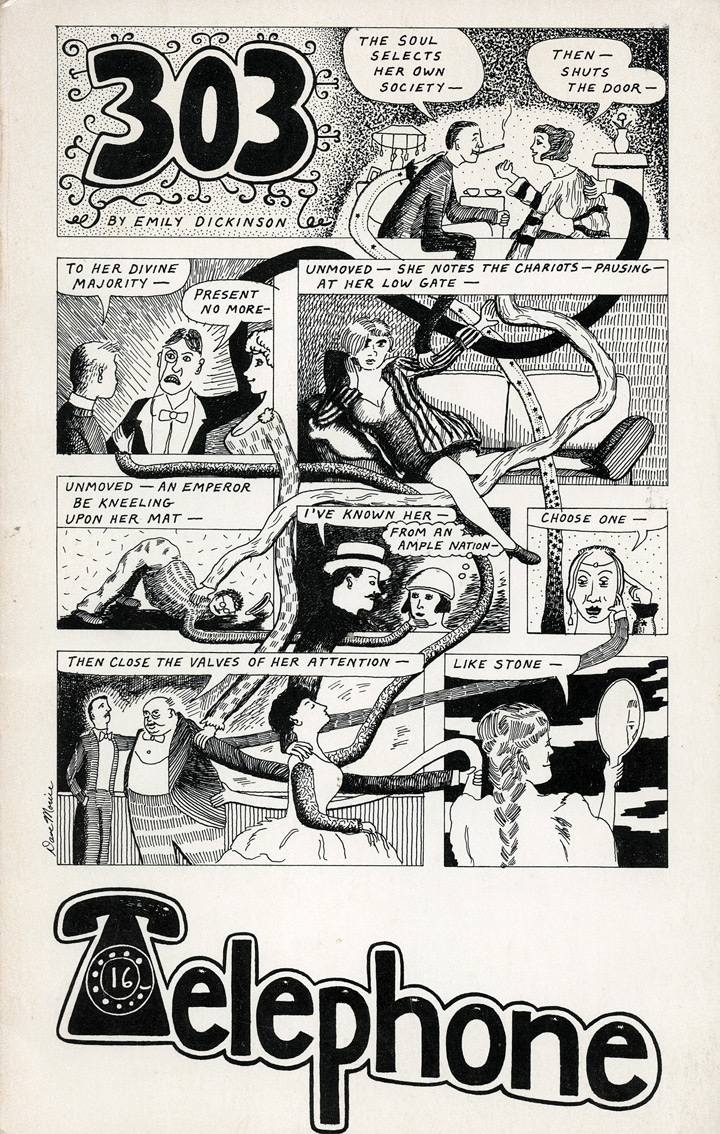

Mandel, Tom. EncY. 1978. Tuumba 16.

Mason, John. Fade to Prompt. 1981. Tuumba 35.

Melnick, David. Men in Aida: Book One. 1983. Tuumba 47.

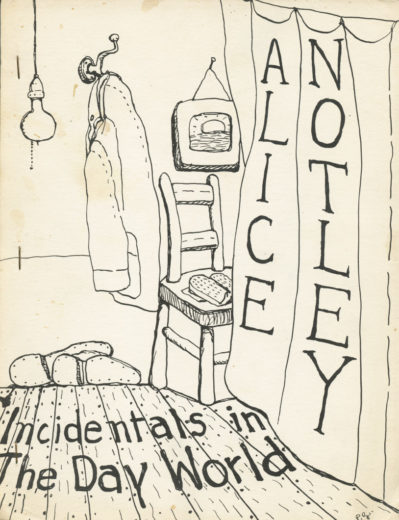

Notley, Alice. Doctor Williams’ Heiresses. 1980. Tuumba 28.

Palmer, Michael. Alogon. 1980. Tuumba 30.

Perelman, Bob. a.k.a. 1979. Tuumba 19.

Perelman, Bob. To the Reader. 1984. Tuumba 49.

Price, Larry. Proof. 1982. Tuumba 42.

Robinson, Kit. Riddle Road. 1982. Tuumba 41.

Robinson, Kit. Tribute to Nervous. 1980. Tuumba 26.

Rodefer, Stephen. Plane Debris. 1981. Tuumba 36.

Seaton, Peter. Crisis Intervention. 1983. Tuumba 45.

Silliman, Ron. ABC. 1983. Tuumba 46.

Silliman, Ron. Sitting Up, Standing, Taking Steps. 1978. Tuumba 17.

Watten, Barrett. Complete Thought. 1982. Tuumba 38.

Watten, Barrett. Plasma / Paralleles / “X”. 1979. Tuumba 21.

Wilk, David. For You/For Sure. 1977. Tuumba 9.

Woodall, John. Recipe: Collected Thoughts for Considering the Void. 1977. Tuumba 10.

Resource

Scans of the complete run of Tuumba are available on the Eclipse website.

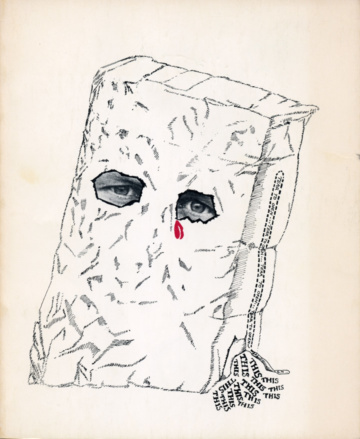

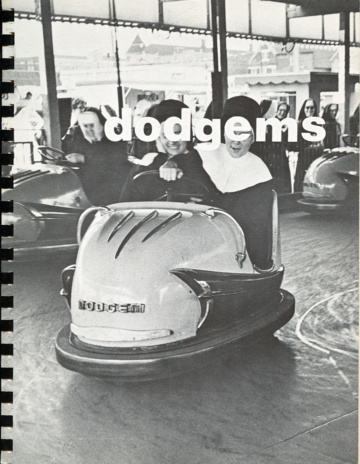

![Dodgems [2], 1979.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/eileen-myles-dodgems-2-1977-r-412x530.jpg)

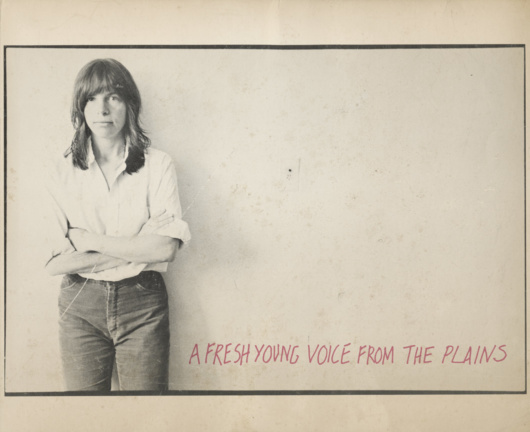

![The World 39 [1983?].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-world-no-39-1983-r-360x467.jpg)

![Detroit Artists Workshop Benefit: Seven Poets, Santa Fe-Albuquerque. Captain Mimeo and the Pepsi Shooter Press Book no. 1. [Duende Press], March 11, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/detroit-family-r-407x530.jpg)

![Wolf Vostell, and Dick Higgins, eds. Fantastic Architecture [1970 or 1971]. Book jacket illustration: Richard Hamilton’s Guggenheim Collage, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vostell-architecture-r-360x498.jpg)

![Maps 1 [1966]. Cover: Herbert Bayer, “Graphic Fragment #2.”](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/maps-1-r-599x530.jpg)

![Maps 3 [1970]: Poems for John Coltrane. Cover by Roger Shimomura.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/MAPS-no-3-1970-r-455x530.jpg)

![Charles Olson, Mayan Letters (1953 [i.e., 1954].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/charles-olson-mayan-letters-divers-press-r-409x530.jpg)

![The Floating Bear 28 [December] 1963. Cover by Alfred Leslie.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/4the-floating-bear_1963_28-405x530.jpg)

![Floating Bear 37 [March–July] 1969. Cover by Wallace Berman.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-floating-bear_1969_37-1-r-410x530.jpg)

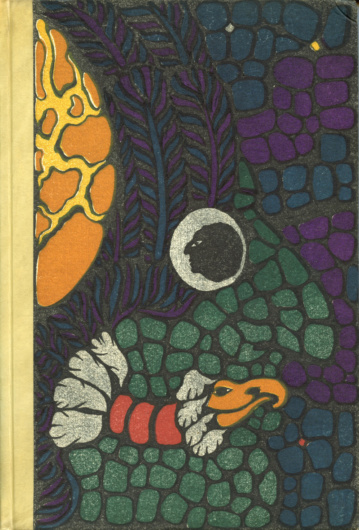

![Jess [Collins], Christian Morgenstern’s Gallowsongs (1970). Illustrations and versions by Jess.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/jess-gallowsongs-black-sparrow-1970-r-400x530.jpg)