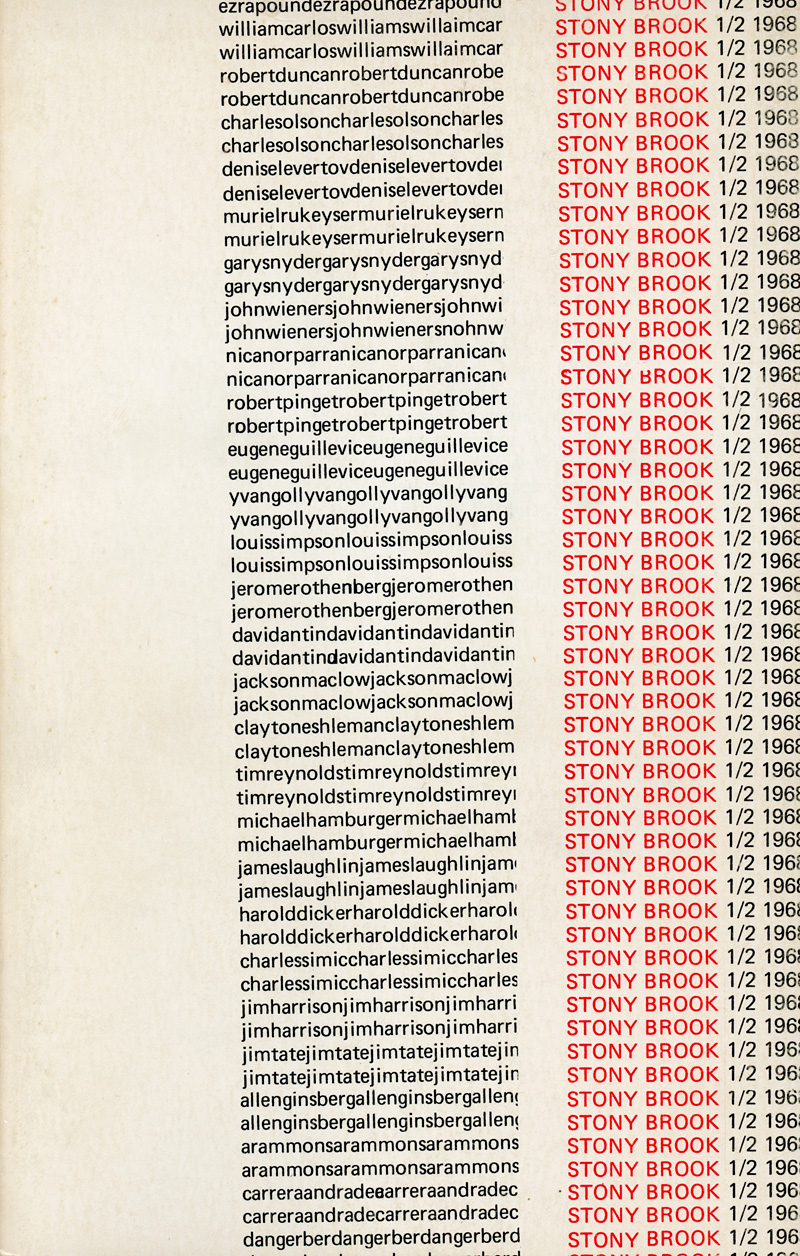

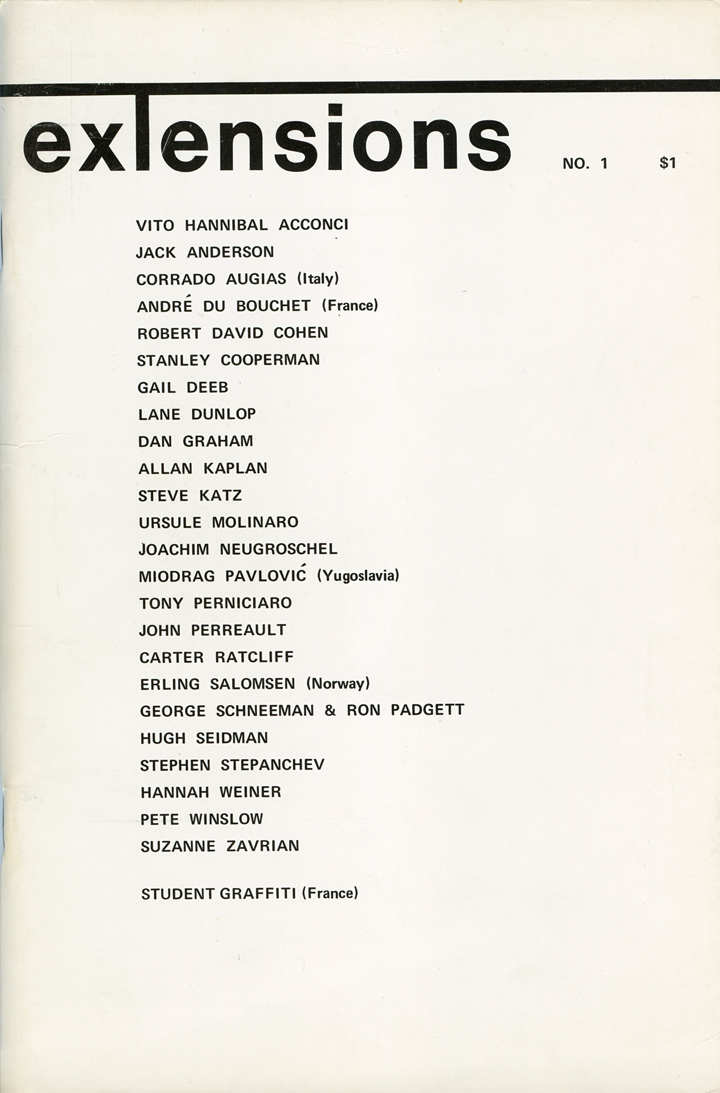

I began Stony Brook, “a journal of poetry, poetics and translation,” in 1968 at Stony Brook University (SUNY), where, since 1966, I’d been teaching full time in the English Department while doing graduate work at NYU. I was inspired both by the poetry energy of downtown New York and the great variety of international poets who came through Stony Brook. A special opportunity to launch the journal arose at the June 1968 Stony Brook international poetry festival, organized by faculty poets Jim Harrison and Louis Simpson, who invited some twelve foreign poets—including Francis Ponge, Zbigniew Herbert, Czesław Miłosz, Eugène Guillevic, Nicanor Parra, and Kofi Awoonor—and some seventy American poets to listen to those twelve, but not themselves give readings—including Robert Duncan, Jackson Mac Low, Allen Ginsberg, Clayton Eshleman, Jerome Rothenberg, Anselm Hollo, Denise Levertov, Gary Snyder, Ed Sanders, Joel Oppenheimer, Milton Kessler, Bill Corbett, Charles Simic, George Hitchcock, and James Tate. Roger Guedalla, a British friend of several years and a graduate student, served as managing/contributing editor for all issues, and J. D. Reed, a graduate student, and Eliot Weinberger, an undergraduate student, were contributing editors to the first issue (Eliot’s uncle became our printer and a board member).

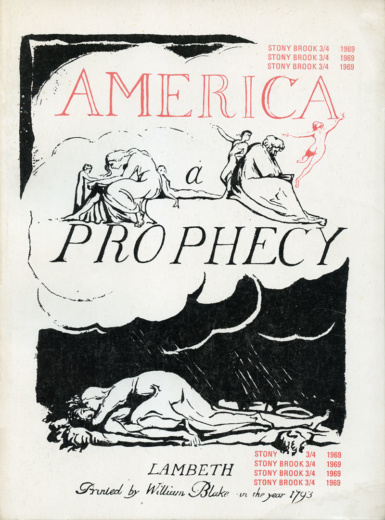

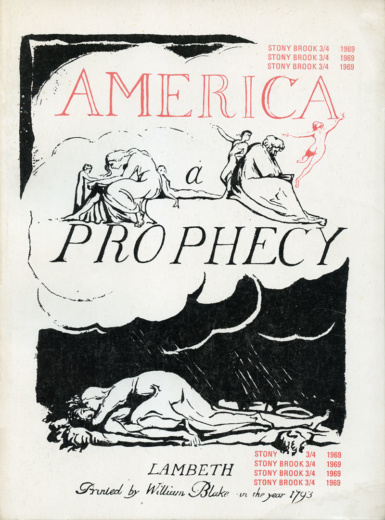

Often referred to as Stony Brook Magazine, though not officially its name, it comprised two large double issues, 1/2 (1968, 258 pages, 6 x 9¼”) and 3/4 (1969, 400 pages, 7 x 9¼”), with a third double issue, 5/6 (same format as 3/4), fully edited and typeset but never printed (for lack of funds). The journal’s editorial concept was to connect the different poetry ecologies then active, along with their conflicting poetics. I had a Blakean, “without contraries no progression” view, related to my own intricate and often conflicting loyalties, and I wanted to juxtapose poets who rarely appeared in the same publication, as an “ideogram” of contemporary practice. I hoped the resulting “Mental Warfare” would produce an interesting poetics discourse. The two-year life of the journal was not enough to test the critical hypothesis very thoroughly, but certain tensions were activated. Stony Brook 3/4 opened with a full b/w facsimile of William Blake’s America a Prophecy (not easily available in 1969).

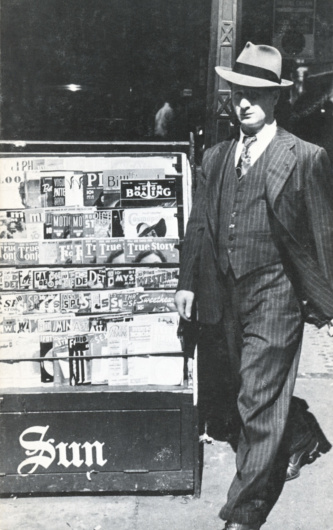

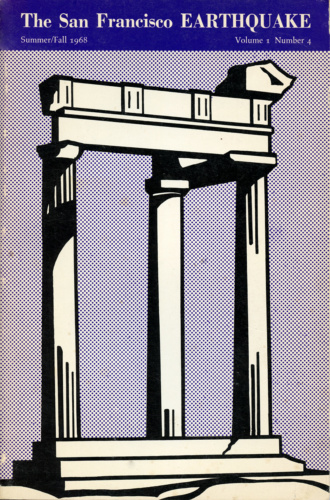

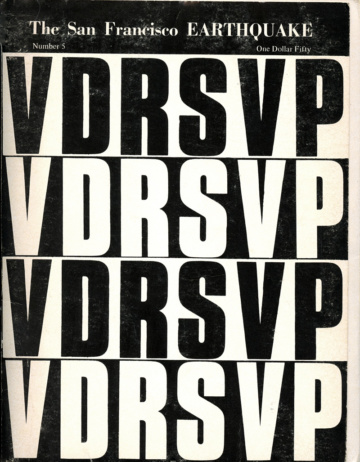

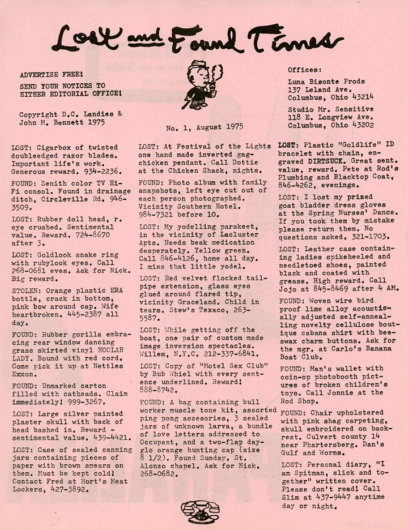

Stony Brook 3/4 (1969).

Stony Brook did assemble an array of unique texts and associations, as reflected by the diverse list of contributing editors: Lawrence Alloway (visual arts), David Antin (linguistics), Kofi Awoonor (African), Leopoldo Castedo (visual arts), Jorge Carrera Andrade (Latin American), Robert Duncan (poetry), Mathias Goeritz (concrete poetry), Michael Hamburger (German), Hugh Kenner (poetics), Daniel Mauroc (French), Enrique Ojeda (Spanish/Latin American), Nicanor Parra (Spanish/Latin American), M. L. Rosenthal (poetry), Jerome Rothenberg (ethnopoetics), Leif Sjöberg (Scandinavian), Charles Simic (Eastern European), Louis Simpson (poetry), Jack Thompson (poetics), and Wai-Lim Yip (Chinese).

Some sixty participants in the first double issue and over a hundred in the second, including poets, writers, artists, translators, critics, scholars, anthropologists, etc., contributed over six hundred pages of poetry, prose, translation (bilingual), visual art, reviews, and commentary from a dozen or so cultures. Notable texts included:

— The first publication since the war of new Cantos of Ezra Pound (made possible by James Laughlin’s personal support for the journal).

— A revival of the Objectivist Anthology poets (George Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Carl Rakosi, and Charles Reznikoff, with commentary by Ezra Pound, Robert Creeley, and Kenneth Cox) in new work and documents.

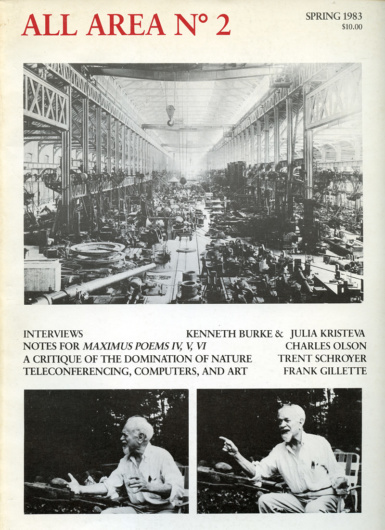

— New poetry by Charles Olson (from Maximus), Muriel Rukeyser, John Wieners, Gary Snyder, James Laughlin, Joanne Kyger, Robert Creeley, Helen Adam, Clayton Eshleman, Jackson Mac Low, David Antin, Jerome Rothenberg, Armand Schwerner, Denise Levertov, Diane Wakoski, David Bromige, Eleanor Antin, Tom Pickard, George Stanley, Jim Harrison, Charles Bukowski, Geoffrey O’Brien, Charles Simic, George Bowering, Michael Hamburger, James Tate, Ifeanyi Menkiti, A. R. Ammons, M. L. Rosenthal, Tim Reynolds, Louis Simpson, Stuart Montgomery, Harold Dicker, George Quasha, Robert Vas Dias, Harold Dull, Willis Barnstone, Raphael Rudnik, and Howard McCord, among others.

— Wai-Lim Yip’s analytical presentation of ancient and modern Chinese poetry, with new translations along with Chinese originals.

— The first presentation of ethnopoetics (I invited Rothenberg to create a new word for the field and become the first editor, which evolved later into Alcheringa journal) by way of substantial excerpts from his forthcoming anthologies, Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe and Oceania (1968) and Shaking the Pumpkin: Traditional Poetry of the Indian North Americas (1972).

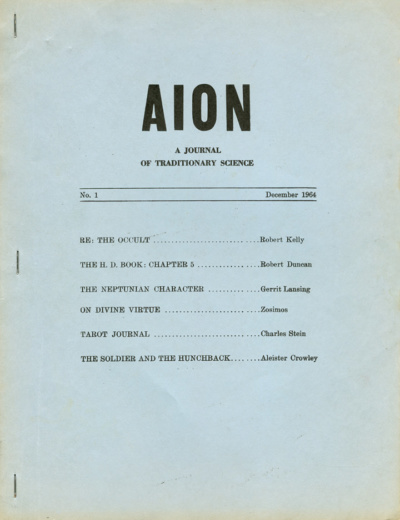

— Robert Duncan contributed sections of The H. D. Book for the first time in a widely circulated literary journal, as well as a rather contentious piece, “A Critical Difference of View,” on reviews by Hayden Carruth and Adrienne Rich, disagreeing with their take, respectively, on Williams and Zukofsky.

— David Antin’s innovatively disruptive, linguistics-based attack on metrical notions in verse, “Notes for an Ultimate Prosody,” with its opening headline, “The contribution of meter to the sound structure of poetry has been trivial,” comprising Part One, but Part Two never appeared anywhere. (This had been a paper for a poetics theory graduate seminar at NYU under M. L. Rosenthal which we both attended, and I persuaded Antin to publish it—though he was hesitant—because it is a unique and challenging analysis of a major issue; apparently never reprinted.)

— Hugh Kenner, in addition to supplying a section of The Pound Era then in progress, gave a supportive response to Antin’s piece. William S. Wilson (writer, art and poetry critic/scholar) challenged Antin’s piece in his “Focus, Meter and Operations in Poetry” and defined an “operational” poetics with emphasis on concrete poetry. This exchange was the main instance of a generated poetics discussion we had hoped for.

— Translations from Francis Ponge, Robert Pinget, Robert Desnos, René Daumal, Eugène Guillevic, Yvan Goll, Daniel Mauroc, Nicanor Parra, Octavio Paz, Jorge Carrera Andrade, Gunnar Ekelöf, Czesław Miłosz, Vasco Popa, Tadeusz Różewicz, Momčilo Nastasijević, Antun Šoljan, Ivan V. Lalić, Branko Miljković, Aleksander Wat, Evgeny Vinokurov, and Miklós Radnóti, among others.

— Translators include Denise Levertov, Galway Kinnell, Muriel Rukeyser, Jerome Rothenberg, Richard Johnny John, Charles Simic, H. R. Hays, Robert Duncan, Raymond Federman, Richard Lourie, George Quasha, Edward Field, Stephen Dolgar, Stephen Berg, S. J. Marks, Victor Contoski, David P. McAllester, and Leif Sjöberg.

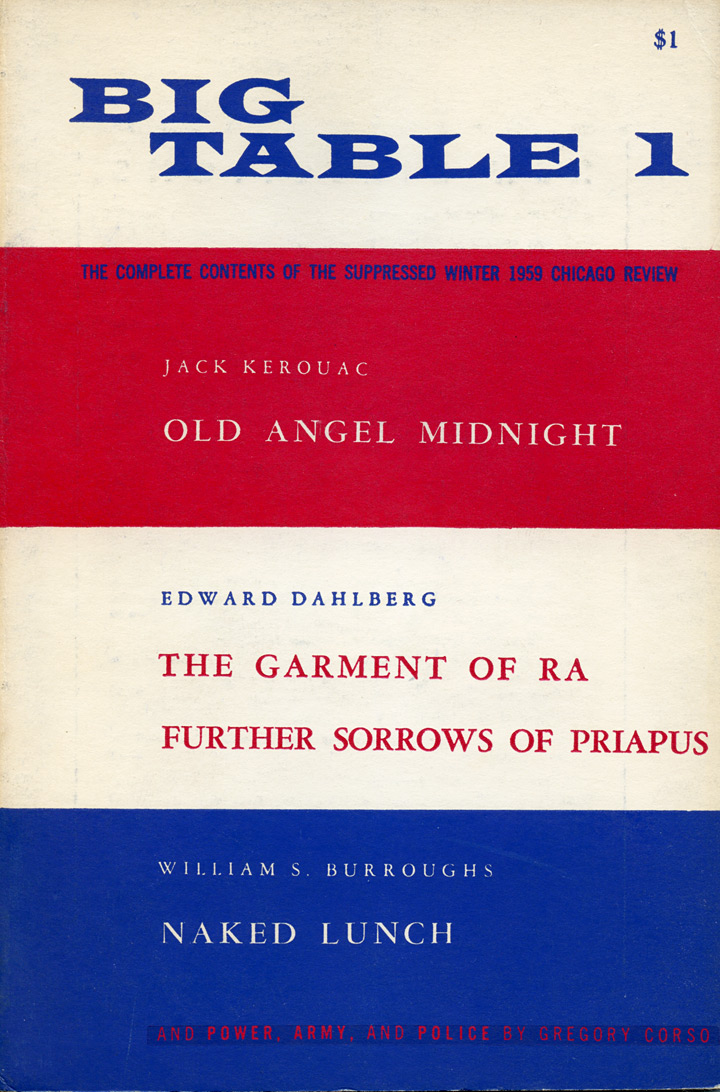

— Documents: Ezra Pound’s “How I began” (1913), Preface to Oppen’s Discrete Series (1934), and “René Crevel” (1939); W. C. Williams, letters to Denise Levertov, Yvan Goll, and William S. Wilson; George Oppen, “On Armand Schwerner”; Edward Dahlberg, Preface to The Flea of Sodom; Robert Creeley, “Basil Bunting: An Appreciation”; Serge Gavronsky, “Interview with Francis Ponge”; Denise Levertov, “Working and Dreaming”; Dell Hymes, “A Study of Some North Pacific Poems”; Louis Simpson, “The Anti-Theorist”; George Bowering, “On the Road: and the Indians at the end”; David P. McAllester, “The Tenth Horse Song: Translation, Comments, Text & Notes”; Richard Grossinger, “Oecological Sections Nos. 24 & 29.”

As a mechanism of underwriting Stony Brook I founded the Stony Brook Poetics Foundation as a tax-exempt, 501(c)(3) organization, hoping the university might eventually agree to support it, which never happened. When after five years my life took me away from Stony Brook, there was no possibility of continuing or publishing the third volume, which contained important work like Paul Blackburn’s Provençal translations (bilingual). Though the magazine could not be sustained, it nevertheless laid the groundwork for an anthology I was coediting at the time with Ronald Gross (subeditors Emmett Williams, John Robert Colombo, and Walter Lowenfels), Open Poetry: Four Anthologies of Expanded Poems (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973), and subsequently (with Susan Quasha), An Active Anthology (Fremont, MI: Sumac Press: 1974). It also initiated my collaboration with Jerome Rothenberg, which, in a couple of years, would lead to America a Prophecy: A New Reading of American Poetry from Pre-Colombian Times to the Present (New York: Random House, 1973).

— George Quasha, Barrytown, New York, April 2017

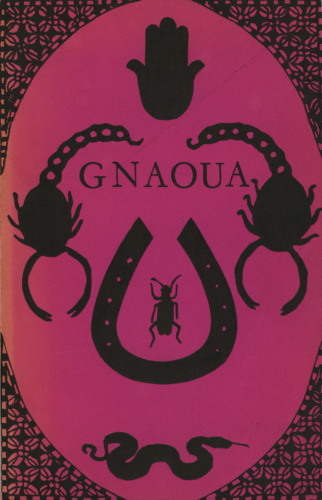

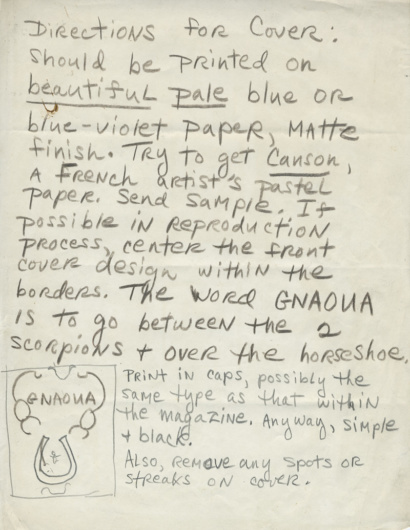

![Panama Rose [Rosalind Schwartz], The Hashish Cookbook (1966).](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/panama-rose-hashish-cookbook-gnaoua-press-1966-r-385x530.jpg)