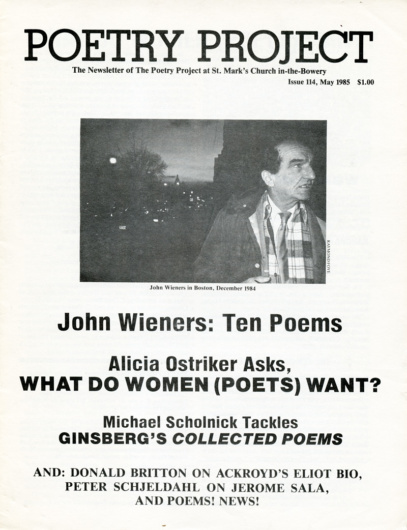

Insane Podium: A Short History

The Poetry Project, 1966–

by Miles Champion

The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery was founded in the summer of 1966 as a direct successor to, and continuation of, the various coffeehouse reading series that had flourished on the Lower East Side since 1960. The first of these, at the Tenth Street Coffeehouse on the gallery block between Third and Fourth Avenues, moved to Les Deux Mégots on East Seventh Street in 1962 (both establishments were co-owned by Mickey Ruskin, who would later open Max’s Kansas City); from March 1963, readings were held at Moe and Cindy Margules’s Café Le Metro at 149 Second Avenue, where the 13th Step sports bar is now.

Allen Ginsberg has traced the lineage back further, to the readings at the MacDougal Street Bar (later the Gaslight Café) in the late 1950s, which were prompted by the popularity of readings organized earlier in that decade on the West Coast by poets associated with the San Francisco Renaissance and the Berkeley Renaissance of the 1940s. Before that, Ginsberg suggests, there was the Paris of the Existentialists (the name Les Deux Mégots—The Two Butts or Fag-Ends—was, after all, a play on Les Deux Magots, the famous Left Bank café), and, predating that by some 2,000 years, the Forum of Ancient Rome.

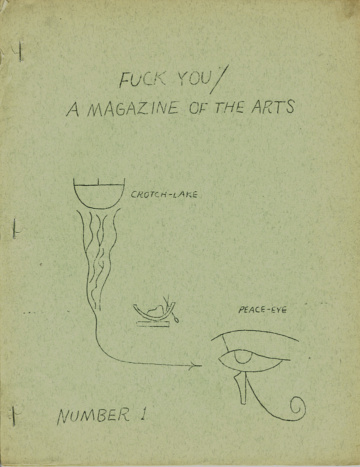

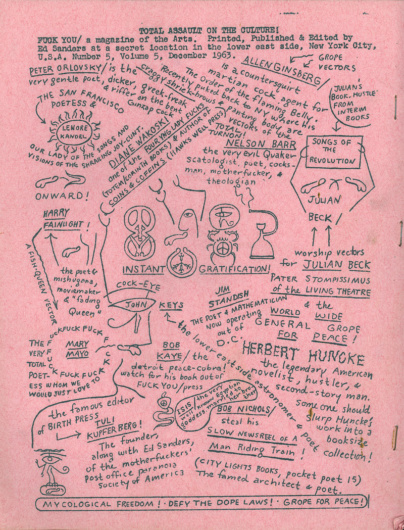

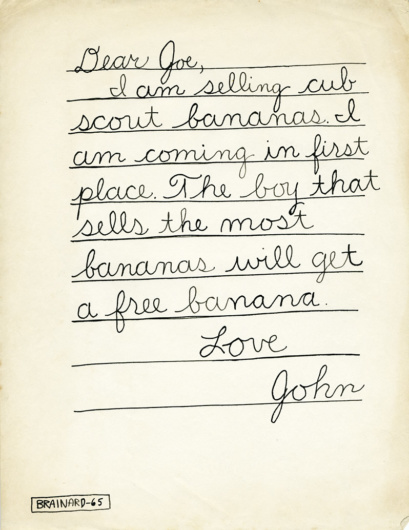

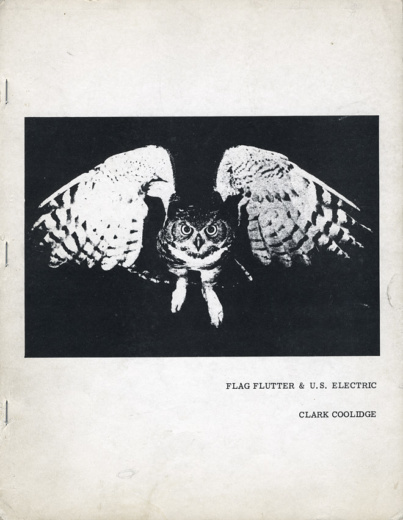

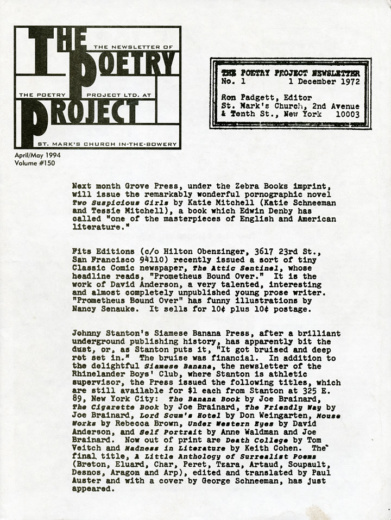

Broadly contemporary with the Poetry Project’s founding were the Sunday afternoon readings hosted by Ted Berrigan at Izzy Young’s Folklore Center on Sixth Avenue at Third Street; Joe Brainard, Joseph Ceravolo, Dick Gallup, Gerard Malanga, Ed Sanders, and Aram Saroyan read there, among others, and Clark Coolidge gave his first-ever reading there in July ’66.

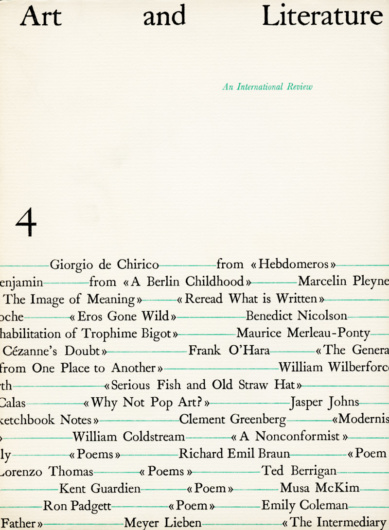

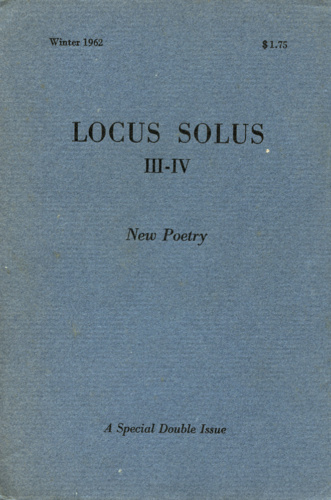

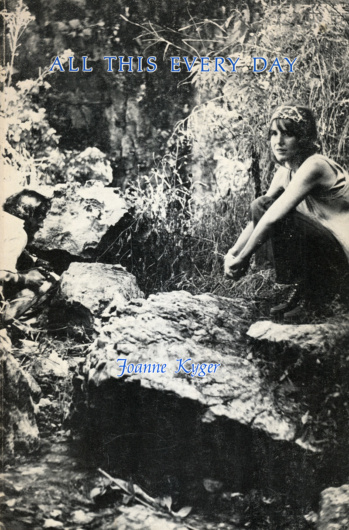

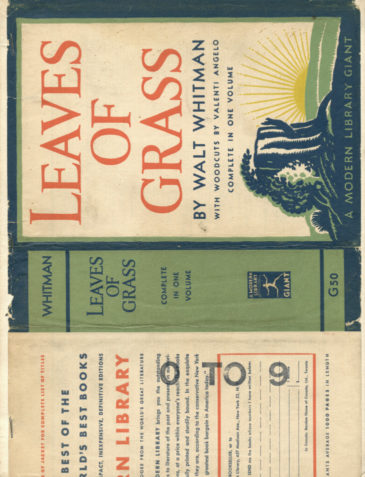

A snapshot of the relevant poetry landscape in the years immediately prior to the Project’s founding would include the publication in 1960 of Donald M. Allen’s groundbreaking anthology The New American Poetry (with its five groupings of Black Mountain, San Francisco Renaissance, Beat, New York School, and Other), and the Vancouver and Berkeley poetry conferences of, respectively, 1963 and 1965.

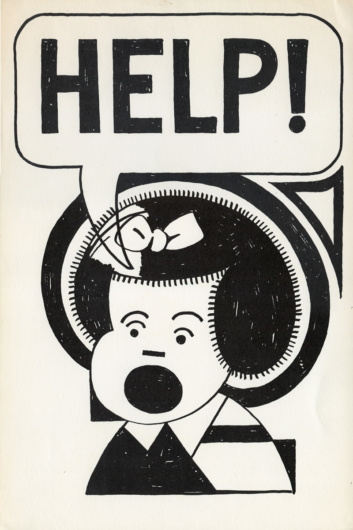

Flyer for a reading by Aram Saroyan at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, January 31, 1968. Date and location are on the flyer’s verso.

When the readings at Café Le Metro came to an end in late 1965, the poets—Paul Blackburn, Carol Bergé, Jerome Rothenberg, and Diane Wakoski among them—found themselves temporarily without a home. Various tensions—racial, political—had pulled the Metro series apart; Moe Margules was a Goldwater Republican, and the already strained relations between him and the Umbra poets—a collective of predominantly African-American writers living on the Lower East Side, including Steve Cannon, Tom Dent, David Henderson, Calvin C. Hernton, Lenox Raphael, Ishmael Reed, Rolland Snellings (later known as Askia M. Touré), Lorenzo Thomas, and Brenda Walcott—had become outwardly hostile by the fall. Also, the going rate for a cup of coffee in 1965 was a dime, and Margules had instituted an unpopular 25¢ minimum. St. Mark’s Church was only a half-block away, and the church’s rector, the Reverend Michael Allen, was very much a community figure on the Lower East Side. (Realtors had yet to coin the term “the east village,” although the bohemian drift east was already underway, having been occasioned by rising rents west of Broadway.) Indeed, Allen had gone so far as to claim artists and writers as his allies, for being among the very few in society who were, as he put it, “doing theology.”

St. Mark’s Church itself had a long history of social activism, and had championed the arts since the 1800s, a commitment that would only intensify in the years 1911–37, under the unorthodox rectorship of the decidedly modernist Dr. William Norman Guthrie. Guthrie was a collaborator of Frank Lloyd Wright’s whose enthusiasm for dance (and incorporation of it into his services) did not sit well with all of his parishioners, or the wider Episcopal Church. For Guthrie, dance—or “eurythmic ritual”—was the earliest art form as well as the most direct language of religion.

In 1919, Guthrie assembled an Arts Committee comprised entirely of people who lived locally, including Kahlil Gibran, Vachel Lindsay, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Martha Graham danced at the church in 1930, as did Ruth St. Denis in 1933, with Guthrie reciting St. Denis’s poems between what the New York Times described as her “exotic religious dances.” (Isadora Duncan almost danced at the church in 1922, but the event was canceled at the last minute—as was a later talk Duncan was scheduled to give—due to the intervention of William T. Manning, the Bishop of New York; the bare feet of certain dancers, it seems, were less acceptable than others.) William Carlos Williams lectured in the Sunday Symposium series in April 1926, and incoming rector in 1943, the Reverend Richard E. McEvoy, introduced a visual arts program. When Reverend Allen arrived in 1959, W. H. Auden was a parishioner (he lived two blocks south on St. Mark’s Place and had a favorite pew at the back of the church) and the Civil Rights Movement was at its height, active nearby in Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village. (Allen rode the “freedom buses” through the South in the early sixties, and in late 1972—two years after stepping down as rector at St. Mark’s—he visited North Vietnam as part of a peace delegation invited by the Vietnam Committee of Solidarity with the American People to address human rights issues in the area.)

![Flyer for a reading by Anne Waldman and Kenward Elmslie at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, May 28, [1969].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/flyer-anne-waldman-kenward-elmslie-r-402x530.jpg)

Flyer by Joe Brainard for a reading by Anne Waldman and Kenward Elmslie at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, May 28, [1969].

In 1961, Archie Shepp—also a member of Umbra—began organizing free jazz concerts in the church’s West Yard on Sunday afternoons. In July 1963, the Umbra collective held a “Freedom North” arts festival at St. Mark’s, saluting the Freedom Movement and showcasing the work of African-American painters, sculptors, photographers, poets, and musicians, including Shepp, Lloyd Addison, Tom Feelings, Al Haynes, Joe Johnson, Charles Patterson, Norman H. Pritchard, Freddie Redd, and Edward Strickland. The first issue of the collective’s magazine,

Umbra, had come out in March (edited by Dent, Henderson, and Hernton), one of the first instances of the marriage of aesthetics and militant separatism that would later be associated with the Black Arts Movement.

In 1964, Ralph Cook, a young playwright who had struck up a friendship with Reverend Allen—and who was head waiter at the Village Gate restaurant, where Sam Shepard was working as a busboy—founded the experimental playwrights’ workshop, Theater Genesis, which would go on to be one of the very first off-off-Broadway theaters (along with Caffe Cino, Judson Poets’ Theater, and La MaMa), operating out of St. Mark’s for the entirety of its fourteen-season run, until its closure in 1977 (Cook’s friendship with Reverend Allen led to him becoming Lay Minister for the Arts at St. Mark’s).

Continue readingClose

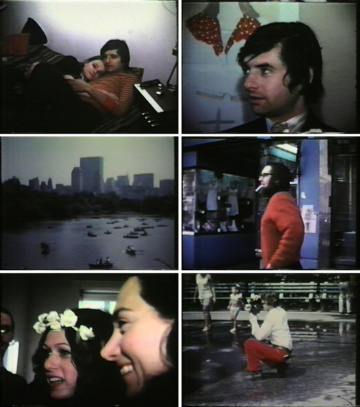

In 1965, Allen invited John Brockman—a young businessman with an office uptown, who was attending Theater Genesis events in the evenings—to coordinate screenings of experimental films at the church, a well-attended series that culminated in Brockman organizing the monthlong Expanded Cinema Festival in November ’65 at the Filmmakers’ Cinémathèque, based on an initial idea of Jonas Mekas’s and featuring performances/screenings by Claes Oldenburg, Nam June Paik, Robert Rauschenberg, Carolee Schneemann, Jack Smith, Andy Warhol, La Monte Young, and many others. (It’s worth noting that Allen issued his invitation to Brockman at a time when the City had banned so-called “underground” films.)

In January 1966, Reverend Allen gave the displaced poets from Café Le Metro a characteristically enthusiastic welcome. A Reading Committee was formed, comprised of Carol Bergé, Paul Blackburn, Allen Planz, Paul Plummer, Jerome Rothenberg, Carol Rubinstein, and Diane Wakoski (George Economou joined later in the year, although the committee was largely a nominal body by then). It would not be contentious to state that, if it were possible to single out just one person as having particularly nurtured the community and context out of which the Poetry Project grew, then that person would be Paul Blackburn. Blackburn had been organizing and attending readings in New York for a decade, often passing the hat to make sure whoever was reading got paid something, and also lugging his Wollensak reel-to-reel tape machine to readings to record them, creating a unique and irreplaceable audio archive in the process (Blackburn’s tapes are now housed in the Archive for New Poetry at UCSD). Jerome Rothenberg has called Blackburn the “moving force” of the readings at Le Metro, and Anne Waldman has described him as the Poetry Project’s “subtle father.”

Various poets read at St. Mark’s in the months leading up to the Poetry Project’s official founding: Harold Dicker, Ree Dragonette, Anselm Hollo, David Ignatow, Jackson Mac Low, Frank Murphy, M. C. Richards, and, on April 28, 1966, John Ashbery, who had recently returned from a ten-year sojourn in Paris, and was introduced by Ted Berrigan.

The task Reverend Allen had set himself was to provide an institutional framework in which both arts and community projects could flourish; he knew funding was necessary if the church’s arts programs were to survive. A month or so after Ashbery’s reading, Reverend Allen received a phone call: Harry Silverstein, a professor of sociology at the New School for Social Research, wanted to know if St. Mark’s could use $90,000.

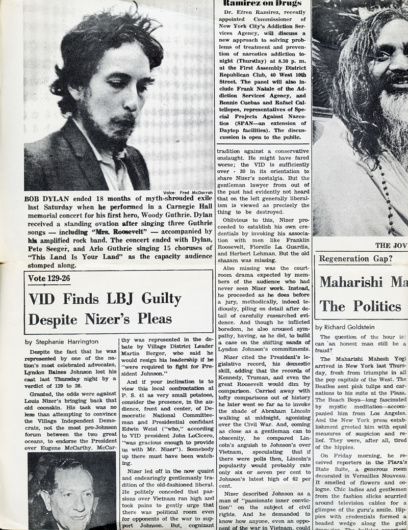

The improbable story of how the incipient arts programs at St. Mark’s would come to receive a two-year grant of a little under $200,000 from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration is related in Bob Holman’s much-quoted (if still-unpublished) “History of the Poetry Project,” which contains transcripts of the oral testimonies of thirty-five people that Holman began interviewing in spring 1978, when the Poetry Project’s director at the time, Ron Padgett, was able to hire him thanks to funds from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, a federally funded reeducation program. The basic facts are outlined in Daniel Kane’s book All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s, and run as follows. In May 1966, the Health, Education and Welfare Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Development found itself with funds earmarked for the socialization of juvenile delinquents—funds that it needed to allocate by the end of the fiscal year, or risk losing entirely. Federal employee Israel Garver called his friend Harry Silverstein to ask if Silverstein had any ideas.

Silverstein’s first call went out to the Judson Memorial Church, which already had a prominent arts program in place; but it turned out that Al Carmines (of the Poets’ Theater) didn’t particularly care for sociologists, and didn’t want them snooping around. And so it came about that the Reverend Allen’s phone rang. Allen couldn’t quite believe it, but Silverstein seemed to be in earnest, and before they knew it they were in discussion with Ralph Cook, Robert Amussen—who was on the Vestry of St. Mark’s and the Board of Theater Genesis, and who also happened to be editor-in-chief at Bobbs-Merrill—and several others. One week later, a grant proposal for a multi-arts project with a full schedule of readings, workshops, screenings, and theater performances (as well as a budget for publications) landed on a desk in Washington. Its title: “Creative Arts for Alienated Youth.”

These various strands shook out into three distinct arts projects. Theater Genesis was, of course, already in place at St. Mark’s, and the poets, as we know, chose the name The Poetry Project (the Olsonian echo was intentional). The third project, the Film Project, proved to be the shortest-lived (under the aegis of St. Mark’s and the New School, at least), due in part to the high cost of rental equipment, the frequency with which this equipment was stolen, and the 16mm equivalent of “musical differences” between its co-runners, Ken Jacobs and Stanton Kaye. Before it fell apart, the Film Project and its equipment were housed in the old Second Avenue Courthouse building (where Anthology Film Archives is now), which St. Mark’s had leased from the City for $100 a year. This was also where the Poetry Project held its first workshops, and where the Project’s first secretary, Anne Waldman, had a satellite office (Lewis Warsh had a desk and phone there, too: he took reservations for Theater Genesis). Jacobs left St. Mark’s after a year, and took the Film Project off in his own direction—as the Millennium Film Workshop—soon after that; the workshop is still running on East Fourth Street today. St. Mark’s held onto the Old Courthouse lease for a number of years, sponsoring Peter Schumann and his Bread & Puppet Theater’s activities there, and giving up the lease when Schumann decided to move on.

The idea, then, was a simple one: the arts projects would run, “youth” would hopefully gravitate toward them (and away from the streets), and the sociologists—Silverstein and his colleague Bernard Rosenberg—would observe and take notes. To quote Michael Allen (from his 1978 interview with Holman): “We were not out to reform kids. It was our commitment that people find their own identities. What we were after was the opposite of juvenile delinquency: a serious, meaningful, committed community.” As it turned out, the New School’s involvement only lasted for a year (it was bureaucratically slow, administratively inefficient), although Silverstein did eventually publish his report in 1971.

The grant allowed for three salaried positions for the poets, and the Project’s first office staff was Joel Oppenheimer (Director), Joel Sloman (Assistant), and Anne Waldman (Secretary). The first official reading at St. Mark’s under the Poetry Project’s newly minted auspices was, fittingly, a solo reading by Paul Blackburn on Thursday, September 22, 1966. When it became apparent that some audience members were unable to get fully behind the idea of readings on Tuesday and Thursday nights (plus there was a clash with a series at the Guggenheim on Thursdays), the Project adopted a format that was well known from Café Le Metro days: open readings on Mondays and featured readers on Wednesdays. The first Wednesday-night reader was Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who read to an audience of 1,200 (with 500 turned away at the door) on October 19. The Reading Committee that had been formed at the start of the year gradually melted away.

The HEW grant included funds earmarked for workshops and a journal to be published three times a year. Sam Abrams, Ted Berrigan, Joel Oppenheimer, and Joel Sloman taught the first workshops; the journal didn’t quite turn out as planned. A professionally printed, perfect-bound journal, edited by Oppenheimer and titled The Genre of Silence, proved to be a one-off (its title was a reference to the muzzling of Isaac Babel’s authorial voice by Joseph Stalin, a clear if clunky sign that the Poetry Project felt somewhat conflicted about the source of its funds, as well as related expectations as to what the journal should be).

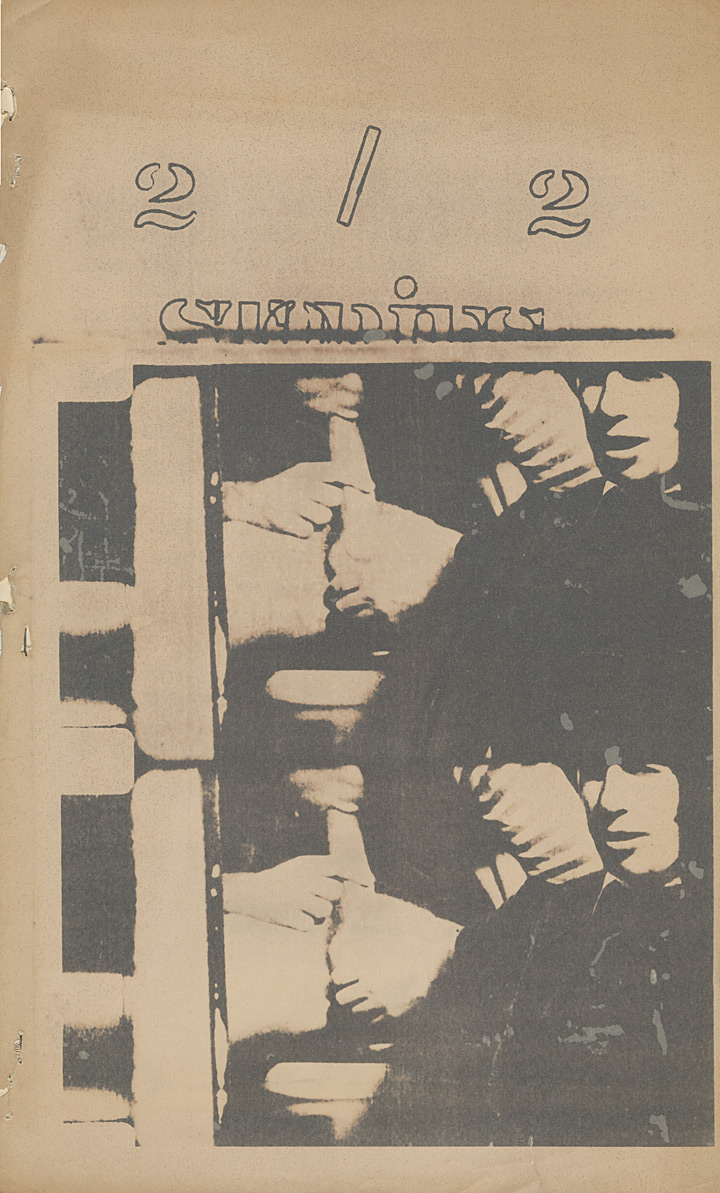

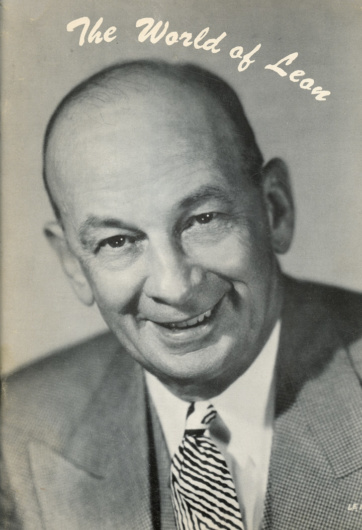

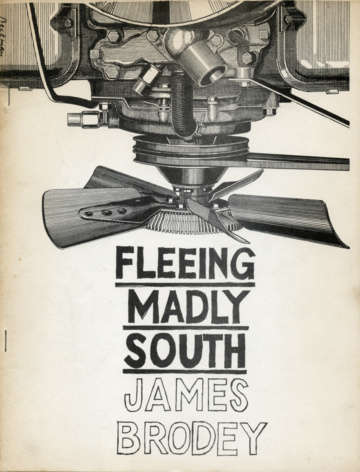

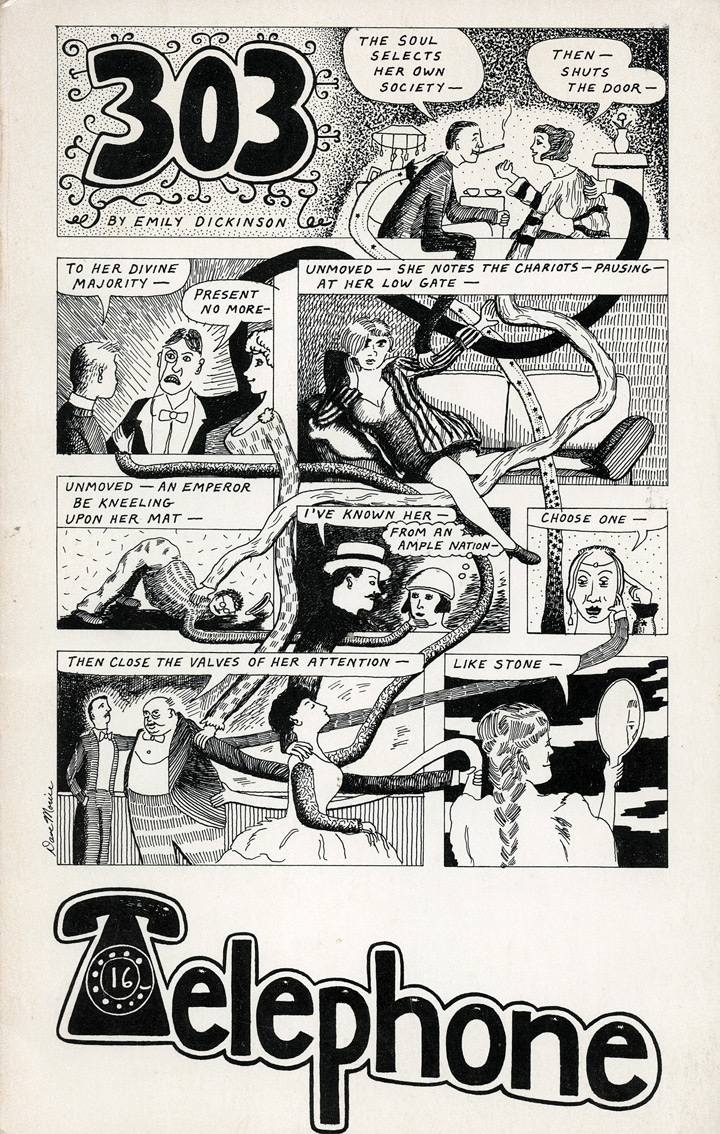

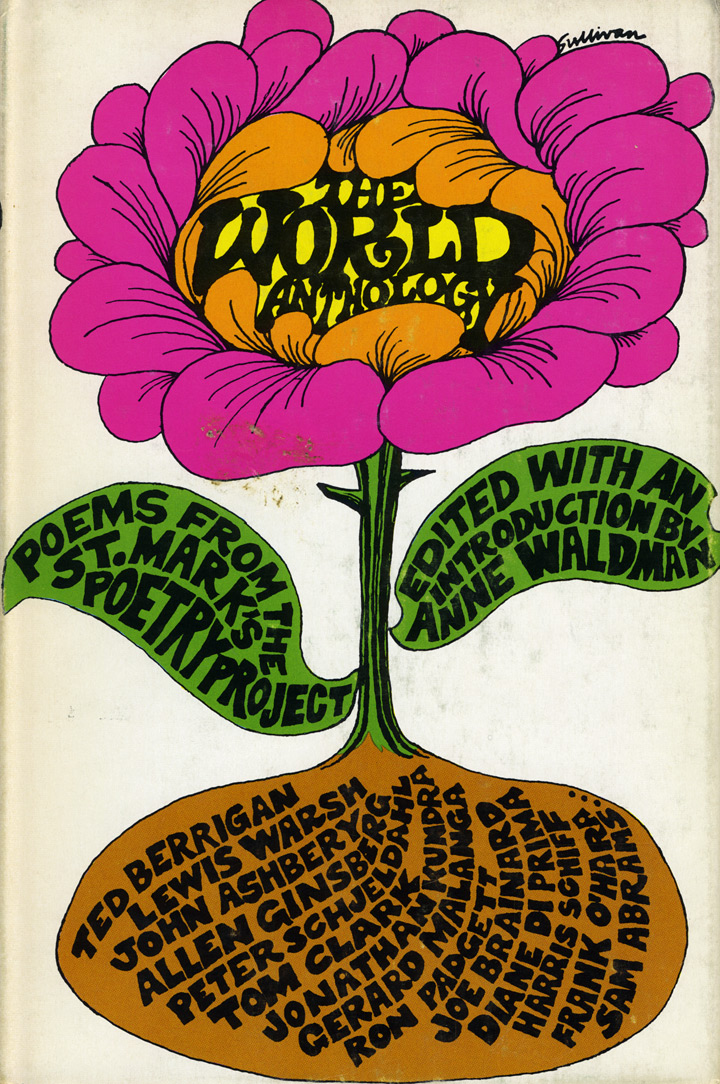

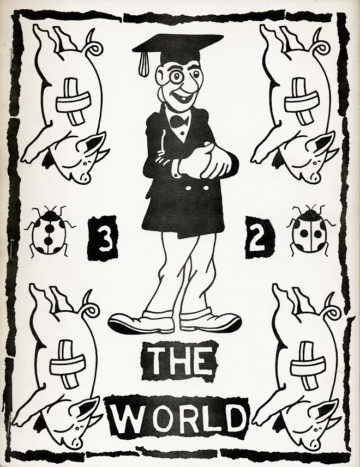

The Project and its community found its needs better met by a proposal of Joel Sloman’s: the quicker and cheaper publication of an in-house mimeographed magazine. The first issue of The World was edited by Sloman and appeared in January 1967, some months before the already assembled Genre of Silence, publication of which had been variously held up. Dan Clark provided the cover art, and the issue contained work by Ted Berrigan, Jim Brodey, Michael Brownstein, Marilyn Hacker, John Perreault, Carol Rubinstein, and Michael Stephens, among others.

This is an an abridged version of Miles Champion’s history of the Poetry Project. The complete essay can be found on the Poetry Project website.

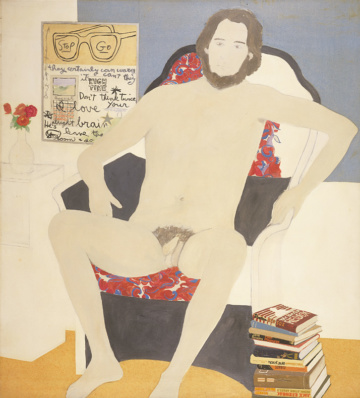

![Dodgems [2], 1979.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/eileen-myles-dodgems-2-1977-r-412x530.jpg)

![The World 39 [1983?].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-world-no-39-1983-r-360x467.jpg)

![Flyer for a reading by Anne Waldman and Kenward Elmslie at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, May 28, [1969].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/flyer-anne-waldman-kenward-elmslie-r-402x530.jpg)

![Flyer for a reading by Larry Goodell and Stephen Rodefer at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, September 26, [no year].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/goodell-rodefer-poetry-project-reading-r-2-360x465.jpg)