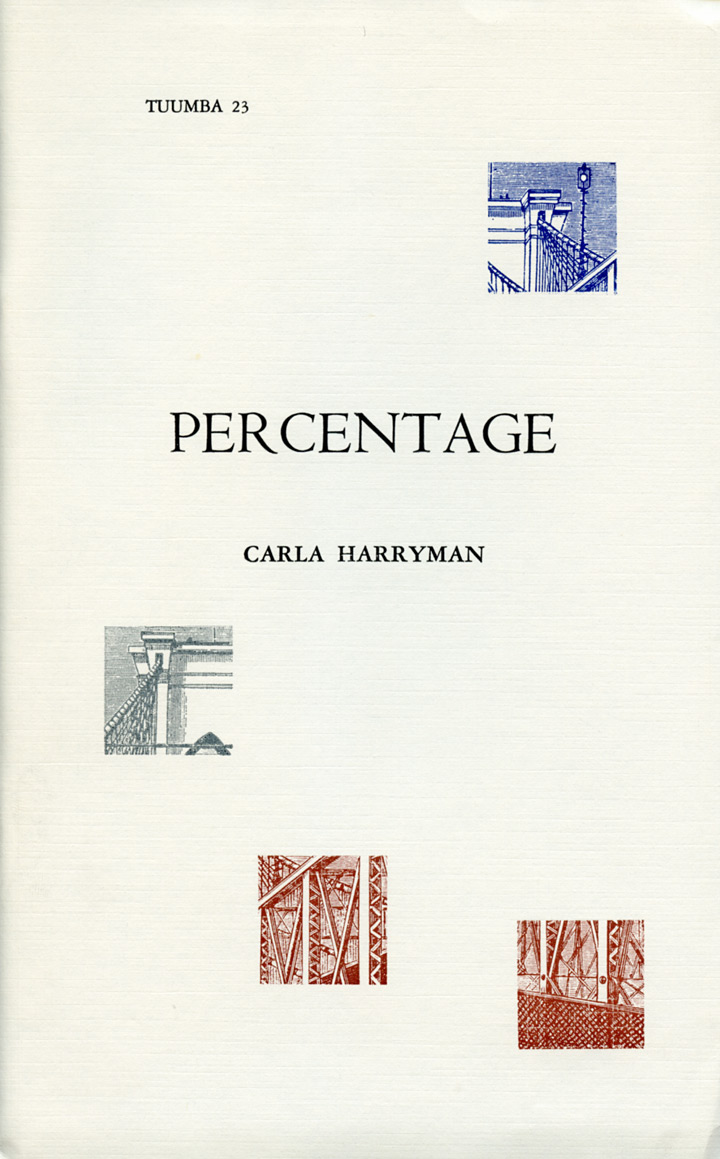

Tooth of Time Review

John Brandi

Guadalupita, New Mexico

Nos. 1–7 (1974–78).

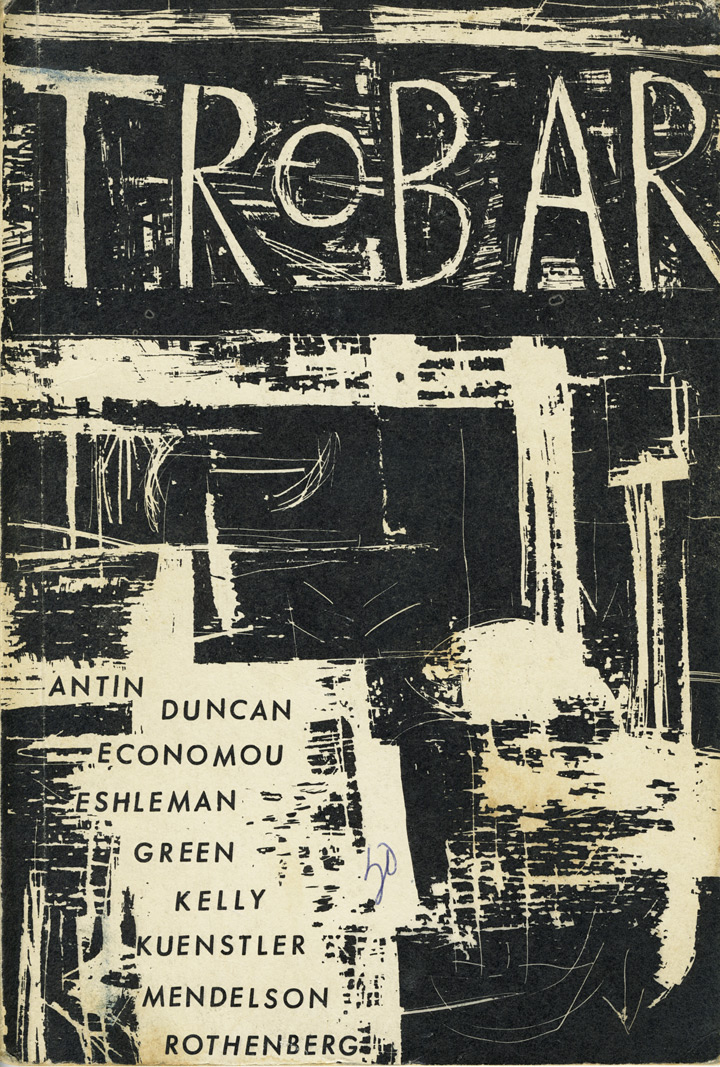

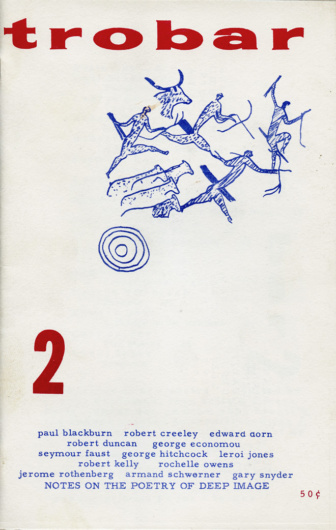

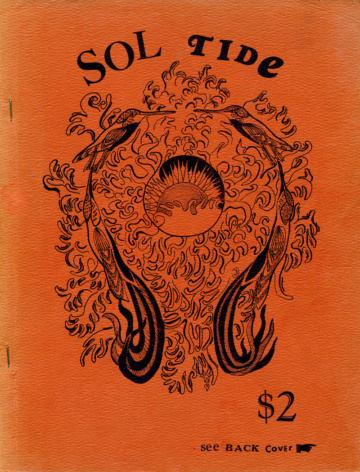

John Brandi, ed. Sol Tide: From Sunrise to Sunset: a Collective Wave (n.d.). Tooth of Time Review 3. Cover and illustrations by the editor.

The first chapbooks and broadsides published by Tooth of Time Books were printed on a 1903 Rotary Neostyle mimeograph, now in the archives of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. Of those early editions, Sol Tide—an 88-page poetry anthology limited to 200 copies—is a favorite.

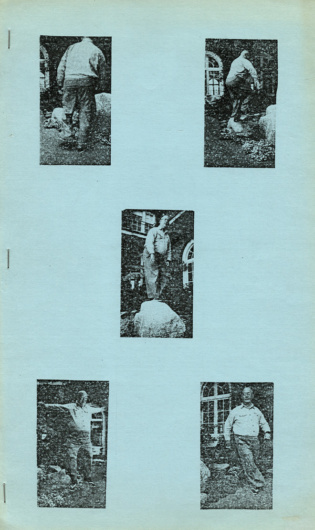

John Brandi at his Rotary Neostyle press, ca. mid-1970s.

Published in the mid-1970s, it sold for $2, plus a buck for postage, direct from my New Mexico mountain cabin. An iconic and classic counterculture production, Sol Tide’s contents were typed on waxed-paper stencils which were wrapped around the mimeo’s hand-inked rotating drum, into which sheets of paper were fed, then collated and bound—with staples, needle and thread, or by treadle sewing machine. Such was the manner of production for the early Tooth of Time editions. The routine included a healthy mix of work and play: nips of tequila, music, a domino game, cookouts, a dip in the spring, readings of Shakespeare under the pines. Many books featured hand-colored drawings: Emptylots, Field Notes From Alaska, A Partial Exploration of Palo Flechado Canyon—to name a few (they appeared under various imprints—Nail Press, Smokey the Bear Press, etc.—while I searched for a fitting name after moving from California to New Mexico).

Sol Tide featured one of the very first poems in English by Japanese poet-wanderer, Nanao Sakaki—whom I had met at Gary Snyder’s Kitkitdizee. The anthology featured works by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Simon Ortiz, Peter Blue Cloud, Charles Plymell, Janine Pommy Vega, Robert Peterson, David Meltzer, Jack Hirschman, Rachel Peters, Gary Paul Nabhan, Larry Goodell, Anaïs Nin, and others. Plus translations by Arthur Sze and Barbara Szerlip, and excerpts from writings by Lama Anagarika Govinda, Chögyam Trungpa, Walt Whitman, Leonardo da Vinci, and William Shakespeare.

Much has been written about Tooth of Time Books. How it was inspired by a hermit I visited in the Andes, mid-1960s. How, in exchange for the use of his mimeo machine, he had me tote buckets of “ink”—used crankcase oil—up a two-kilometer hill to his shack. How he advised me: “Do it yourself, don’t wait for someone from the mainstream to give you the go-ahead.” How I brought my own vintage mimeograph to New Mexico in 1971, setting it up (along with a 1940s Remington “noiseless” typewriter) inside a plastic-covered wikiup—a temporary shelter while a pole-frame cabin was being constructed.

Arthur Sze, Two Ravens (1976). Tooth of Time Review 4. Cover and illustrations by John and Gioia Brandi.

Tooth of Time Books was named after a domed-rock promontory north of the cabin site. Sol Tide’s colophon indicated “The press is devoted to journal jottings, poetry, prose, song/dance & alchemistic probings concerned with exploration/meditation/narration related to wanderings/settlings over/in astral & geographical hemispheres.” Manuscripts were solicited. Production relied “on maximum participation by songsters, usually in the form of typing, preparing stencils, & sharing paper costs.” This required authors to show up, albeit with a forewarning: “We do not operate a dude ranch, there is no electricity or plumbing, water is drawn from a spring, a small garden feeds us. As Jaime de Angulo would say: ‘if you are looking for comfort, don’t come here! You will have to sleep in a tent or under the stars. This place is far from civilization.’”

Tooth of Time Books has been featured in two Museum of New Mexico exhibitions, Lasting Impressions: The Private Presses of New Mexico and Voices of the Counterculture in the Southwest. As it developed from mimeo books to small-press trade editions (featuring such authors as Arthur Sze, Harold Littlebird, Luci Tapahonso, and Nanao Sakaki) the press garnered support from the National Endowment for the Arts. In the year 2000 Tooth of Time Books resumed as when first founded: limited-edition, hand-colored chapbooks and broadsides. The mimeograph days, however, have come to an end.

— John Brandi, El Rito, New Mexico, March 2017

Tooth of Time Publications (complete)

Books

Baber, Bob Henry, ed. Time is an Eightball: Poems from Juvenile Homes & the Penitentiary of New Mexico. 1984.

Brandi, John. Poems from the Green Parade. 1990.

Brandi, John. River Following. 1997. Yoo-Hoo Press / Tooth of Time.

Brandi, John. Sky Hourse / Pink Cottonwood. 1980.

Brandi, John. Shadow Play. 1992. Light and Dust / Tooth of Time.

Brandi, John. Stone Garland. 2000.

Brandi, John. That Crow That Visited Was Flying Backwards. 1982.

Brandi, John. That Crow That Visited Was Flying Backwards. 1984. Revised edition.

Brandi, John. Visits to the City of Light. 2000. Mother’s Milk / Tooth of Time.

Brandi, John and Steve Sanfield. Postage Due. 2011. Backlog / Tooth of Time.

Brandi, John, ed. Dog Blue Day: An Anthology of Writing from the Penitentiary of New Mexico. 1985.

Catacalos, Rosemary. Again For The First Time. 1984.

Connor, Julia. Making the Good. 1988.

Crews, Judson. The Noose. 1980. Duende / Tooth of Time.

Kage. Only the Ashes. 1981. Translated by Steve Sanfield.

Lamadrid, Enrique, ed. En Breve: Minimalism in Mexican Poetry 1900–1985. 1988.

Lamadrid, Enrique and Mario Del Valle, eds. Un Ojo en el Muro / An Eye Through the Wall: Mexican Poetry 1970–1985. 1986.

Lau, Carolyn. Wode Shuofa (My Way of Speaking). 1988.

Littlebird, Harold. On Mountain’s Breath. 1982.

Noyes, Stanley. The Commander of Dead Leaves. 1984.

Noyes, Stanley. My Half-Wild West. 2012.

Sakaki, Nanao. Real Play. 1981.

Sanfield, Steve. A New Way. 1983.

Sanfield, Steve and John Brandi. Clouds Come and Go. 2015.

Sze, Arthur. Two Ravens. 1984.

Sze, Arthur. The Willow Wind. 1981.

Tapahonso, Luci. Seasonal Woman. 1982.

Tarn, Nathaniel. At the Western Gates. 1985.

Vega, Janine Pommy. Drunk on a Glacier, Talking to Flies. 1988.

Zarco, Cyn. Circumnavigation. 1986.

Early Tooth Of Time (the mimeograph days)

The following chapbooks were printed on the 1903 Rotary Neostyle mimeograph machine, given to John Brandi by Fred Marchman—painter, poet, and amigo from Peace Corps days, mid ‘60s. When Fred returned to the U.S. in 1968, he used the Neostyle to print his own books (Ecuadernos, and others) under the imprint: Nail Press. John Brandi eventually changed the name to Tooth of Time Books, after moving to New Mexico, Spring, 1971.

Brandi, John. Emptylots: Poems of Venice and L.A. 1971. Nail Press.

Brandi, John. Firebook. 1974. Smoky the Bear Press (a.k.a. Nail Press).

Brandi, John. A Partial Exploration of Palo Flechado Canyon. 1973. Nail Press.

Brandi, John. The Phoenix Gas Slam. 1974. Nail Press.

Brandi, John. San Francisco Lastday Homebound Hangover Blues. 1973. Nail Press.

Brandi, John. Smudgepots. 1974. Nail Press.

Brandi, John. Three Poems for Spring. 1975. Tooth of Time.

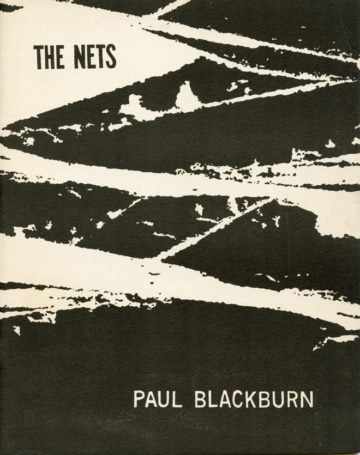

Brandi, John. Turning Thirty Poem. 1974. Nail Press (cover) / Duende (interior). Brandi, John, ed. Sol Tide: From Sunrise to Sunset: a Collective Wave. 1976. Tooth of Time. Brandi, John, ed. Poems and Storys: by Children of Coyote Valley School. 1975. Tooth of Time. Curtis, Walt. Wauregon. 1974. Nail Press. Felger, Richard. Dark Horses and Little Turtles. 1974. Nail Press. Marchman, Fred. Dr. Jomo’s Handy Holy Home Remedy Remedial Reader. 1973. Nail Press. Marchman, Fred. Ecuadernos, vols I, II, III. 1968. [Nail Press]. Martino, Bill. Fallen Feathers. 1973. Nail Press The seven issues of the Tooth of Time Review monograph issues are Bird, Leonard. River of Lost Souls. 1976. Tooth of Time Review 6. Brandi, John. Andean Town: Circa 1980. 1978. Tooth of Time Review 7. Illustrated with photographs by John Powell. Brandi, John, ed. Sol Tide: From Sunrise to Sunset: a Collective Wave. (n.d.). Tooth of Time Review 3. Cover and illustrations by the editor. Felger, Richard. Dark Horses and Little Turtles. 1974. Tooth of Time Review 1. Cover and illustrations by the author. Sanfield, Steve. Back Log: A Cycle of Hoops from the Sierra Foothills. 1975. Tooth of Time Review 2. Sze, Arthur. Two Ravens. 1976. Tooth of Time Review 4. Cover and illustrations by John and Gioia Brandi. Willems, J. Rutherford. Amidamerica. 1976. Tooth of Time Review 5.Continue reading