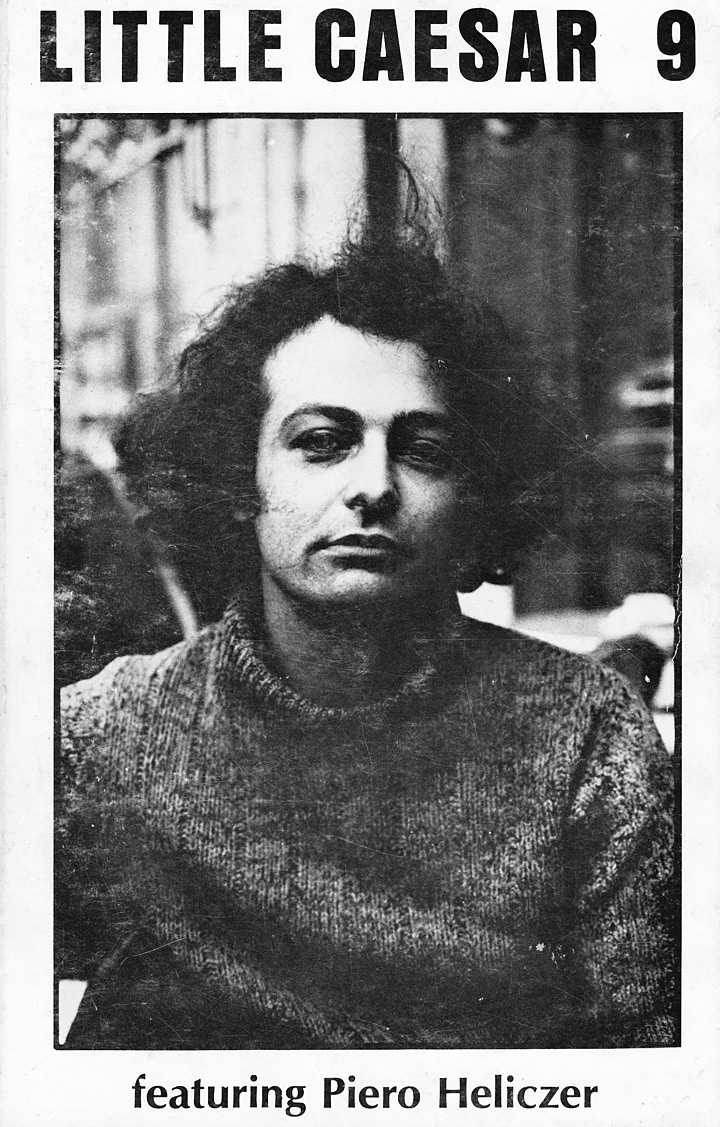

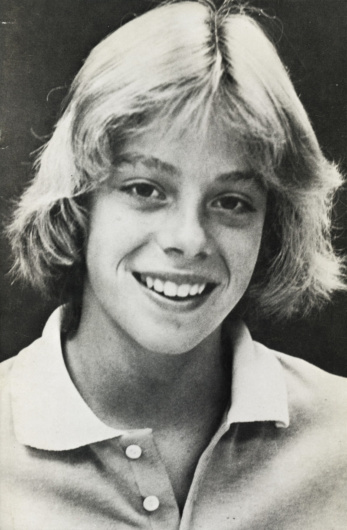

Despite its visual resemblance to the teen idol magazine Tiger Beat (the covers tell the story, featuring images of Adolphe Menjou, John F. Kennedy, Jr. at age sixteen, Arthur Rimbaud, Warhol star Eric Emerson, poet John Wieners, and completely naked rock star Iggy Pop), Little Caesar was a very serious attempt to widen the subjects of and audiences for poetry: “We want a literary magazine that’s read by Poetry fans, the Rock culture, the Hari Krishnas, the Dodgers. We think it can be done, and that’s what we’re aiming at…. We have this dream where writers are mobbed everywhere they go, like rock stars and actors. People like Patti Smith (poet/rock star) are subtly forcing their growing audiences to become literate, introducing them to Rimbaud, Breton, Burroughs and others. Poetry sales are higher than they’ve been in fifteen years.

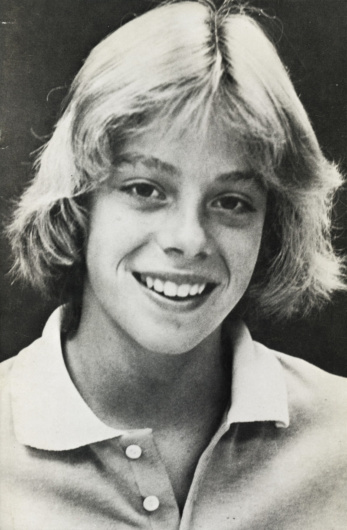

Dennis Cooper, Tiger Beat (1978).

In Paris ten-year-old boys clutching well-worn copies of Apollinaire’s Alcools put their hands over their mouths in amazement before paintings by Renoir and Monet.” Running along pretty much like a “punk poetry ’zine” for its first three issues, Little Caesar then shifted gears a bit, devoting issue 4 to Rimbaud, 5 to poet, filmmaker, and photographer Gerard Malanga, 6 to John Wieners, and 9 to Piero Heliczer. With issue 8 it was back to a neo-punk look and sported a “new wave rock theme,” including an interview with Johnny Rotten and an article by Jeff Goldberg, himself the editor of the rock music–influenced Contact. Goldberg wrote on the Ramones and the “Origins of the New Wave: Forest Hills.” The Saroyan/Wylie/Bockris Telegraph Books series provided both a visual and literary model, but Little Caesar was strikingly of its time, perfectly Californian, new wave, and queer without providing a manifesto for anything, being in your face about most things and up front about few. In addition to the anthology Coming Attractions, books published by Little Caesar Press included Tim Dlugos’s Je suis ein Americano, Ronald Koertge’s Sex Object, a newly translated version of Rimbaud’s Voyage en Abyssinie et au Harrar, Gerard Malanga’s 100 Years Have Passed, and editor Cooper’s collection of poems Tiger Beat. Cooper went on to organize the fantastically successful Beyond Baroque Readings in Venice, California, and is a novelist of some power, grace, and controversy.

Little Caesar books (complete)

Brainard, Joe. Nothing to Write Home About. 1981. Cover art by the author.

Britton, Donald. Italy. 1981. Cover by Trevor Winkfield.

Blakeston, Oswell. Journeys End in Young Man’s Meeting. 1979. Cover photograph by Peter Warfield.

Clark, Tom. The End of the Line. 1980. Cover art by the author.

Congdon, Kirby. Fantoccini: A Little Book of Memories. 1981. Cover photograph by Nita Bernstein.

Cooper, Dennis. Tiger Beat. 1978.

Cooper, Dennis, ed., assisted by Tim Dlugos. Coming Attractions: An Anthology of American Poets in Their Twenties. 1980. Cover art by Duncan Hannah.

Dlugos, Tim. Entre Nous: New Poems. 1982. Cover photograph by Rudy Burckhardt.

Dlugos, Tim. Je suis ein Americano. 1979. Cover photograph by Richard Elovich.

Equi, Elaine. Shrewcrazy. 1981. Drawings by Steven F. Giese.

Gerstler, Amy. Yonder. 1982. Cover photographs by Judith Spiegel.

Gooch, Brad. Jailbait and Other Stories. 1983. Cover photography by Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Hall, Steven. New and Improved. 1981. Cover photography and design by Sheree Levine.

Koertge, Ron. Sex Object. 1979.

Koertge, Ron. Dairy Cows. 1982. Cover art by Bill Womack.

Krusoe, James. Jungle Girl: Poems. 1982. Cover art by Henri Rousseau.

Lally, Michael. Hollywood Magic. 1982. Cover photograph by Lynn Goldsmith.

MacAdams, Lewis. Africa and the Marriage of Walt Whitman and Marilyn Monroe. 1982. Cover art and design by Henk Elenga. Small poster laid in.

Malanga, Gerard. 100 Years Have Passed: Prose Poems. 1978. Cover photograph by the author.

Continue readingClose

Myles, Eileen. Sappho’s Boat. 1982.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Travels in Abyssinia and the Harar. 1979. Translated by Scott Bell.

Schjeldahl, Peter. The Brute: New Poems. 1981. Cover and drawings by Susan Rothenberg.

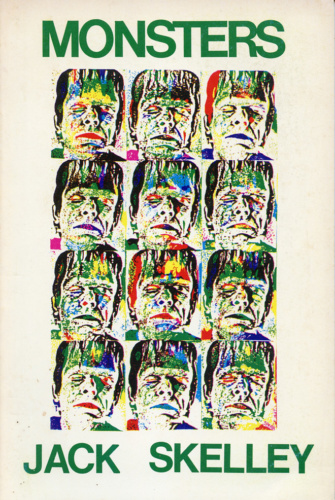

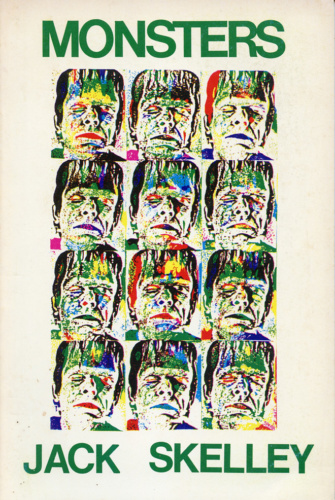

Skelly, Jack. Monsters. 1982. Cover designed by Stephen Spera from a photograph by Sheree Levin.

Jack Skelly, Monsters (1982). Cover designed by Stephen Spera from a photograph by Sheree Levin.