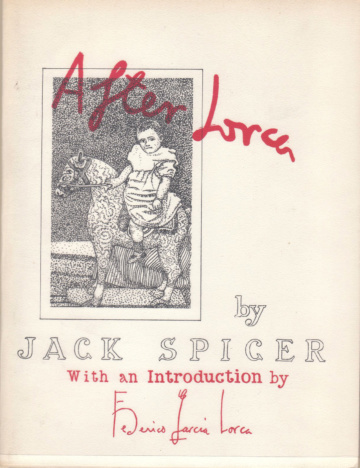

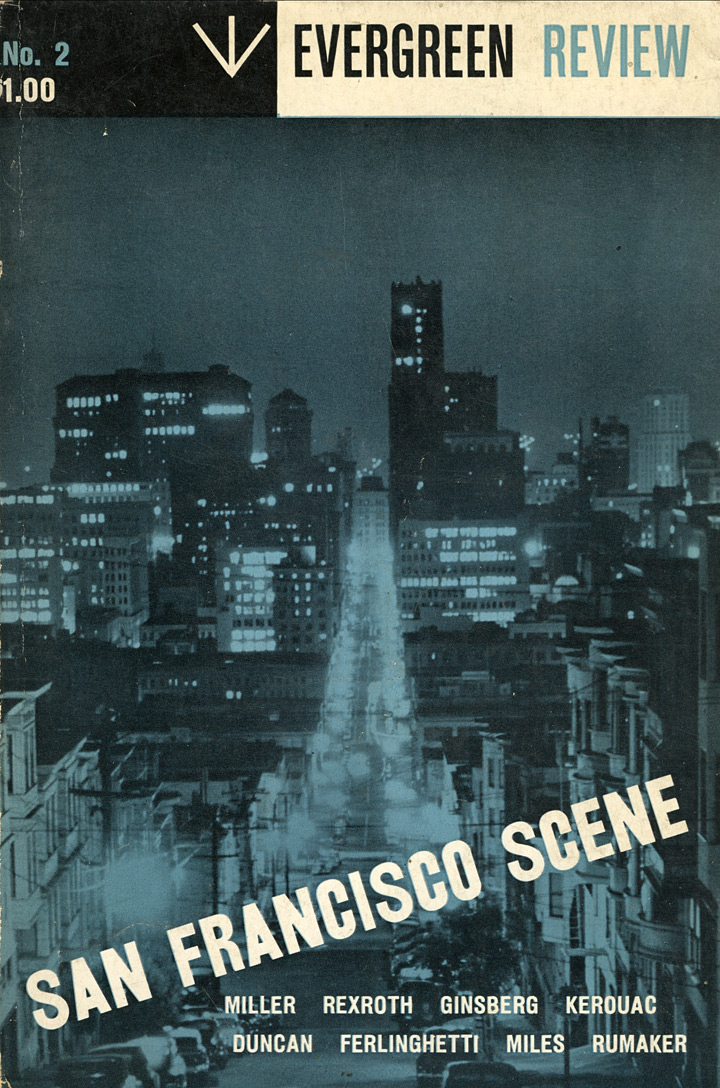

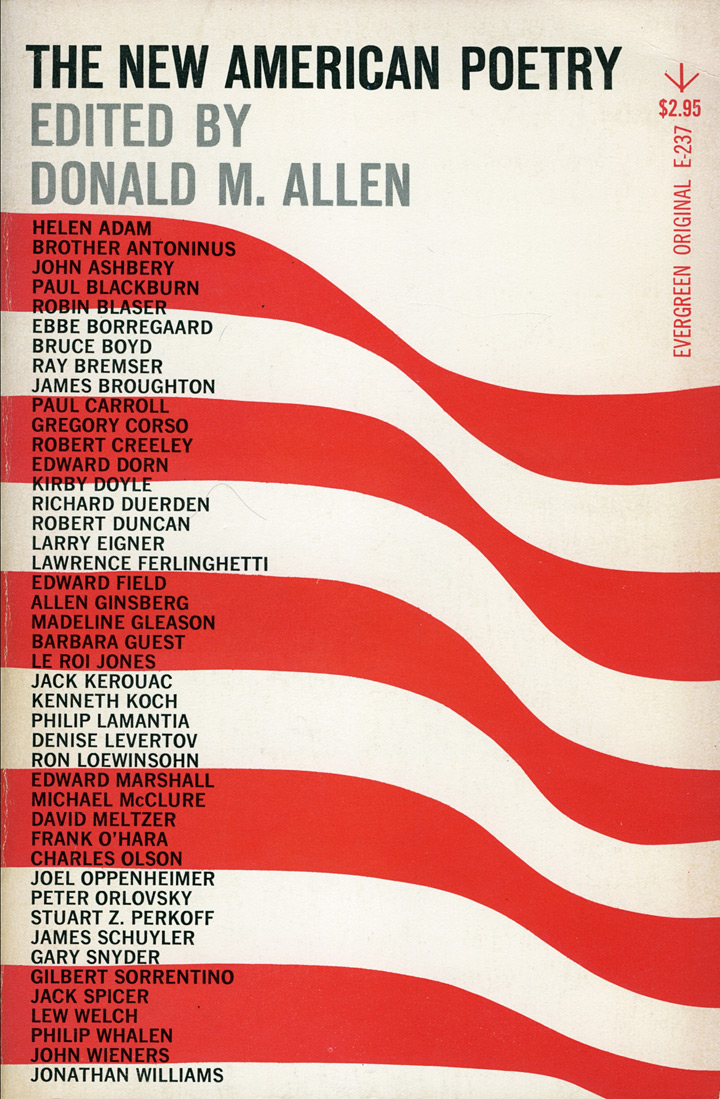

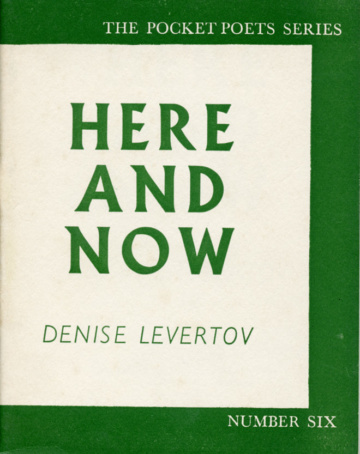

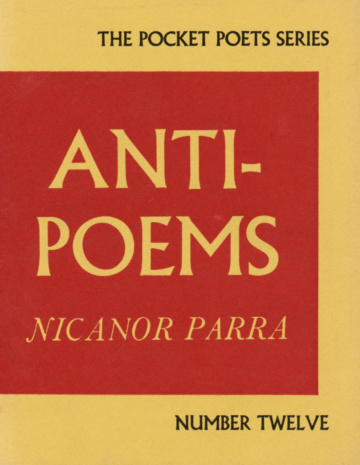

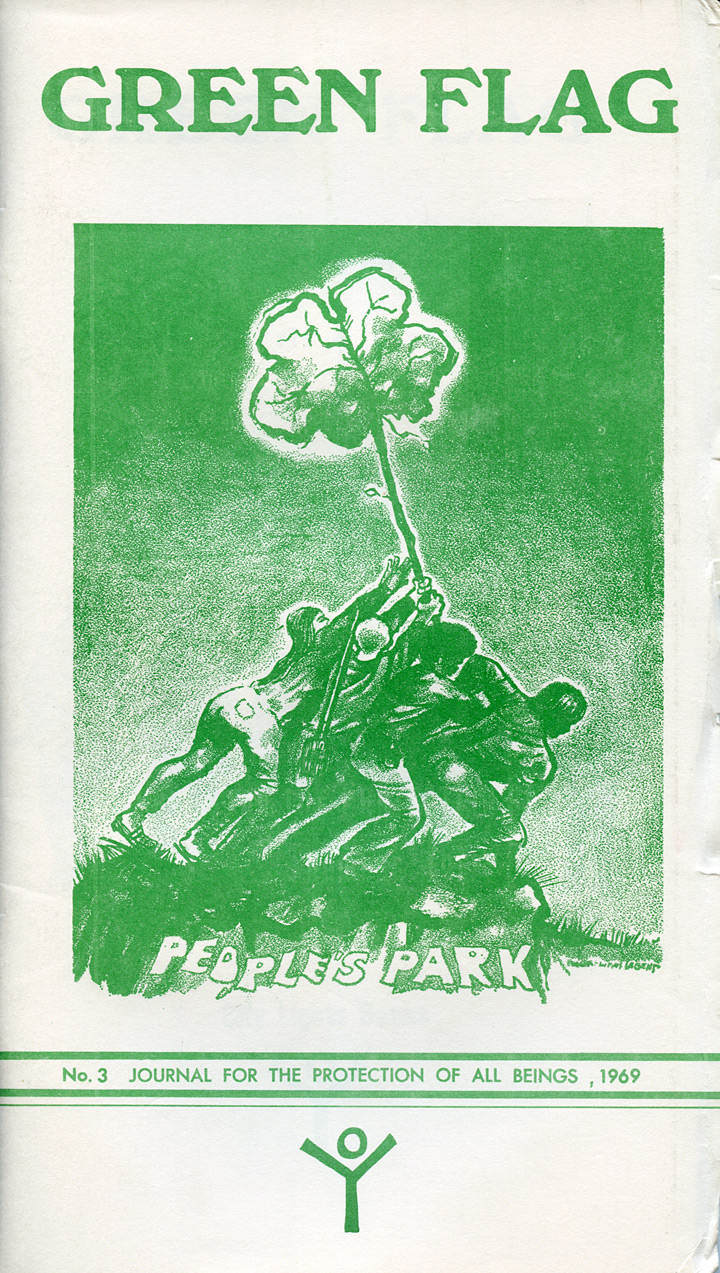

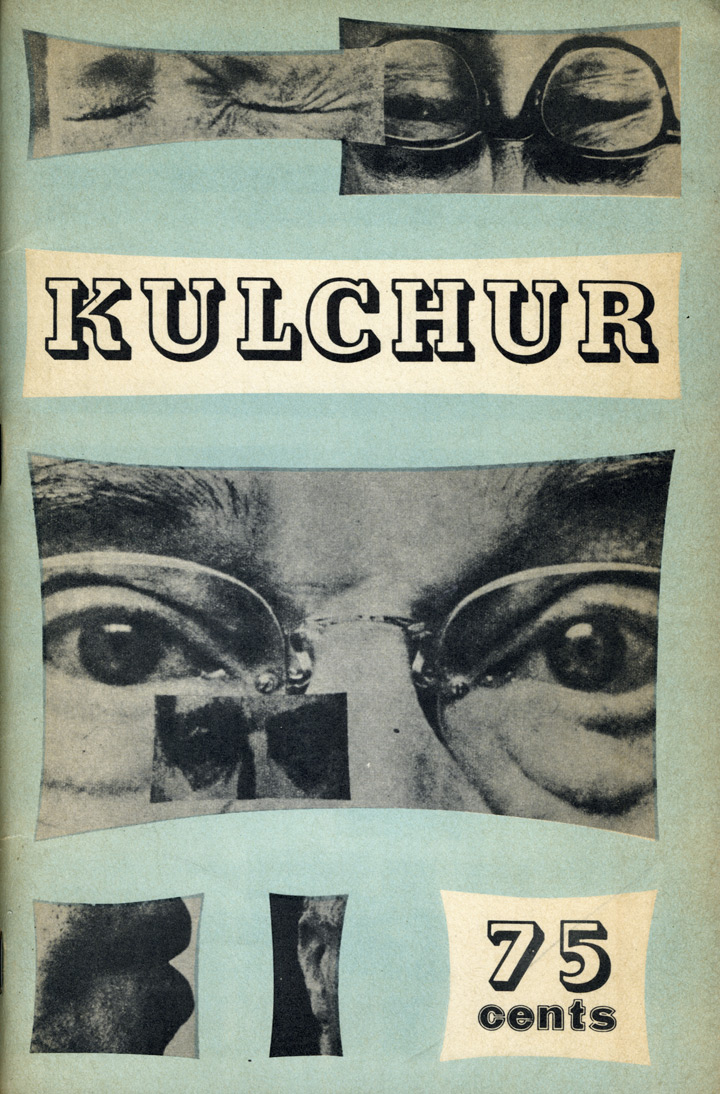

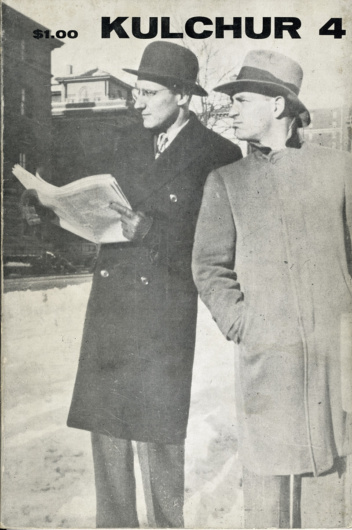

“No Jaz, it’s hopeless. You’re never going to make a writer.” “Jaz” was James Laughlin IV, a bored college freshman who had taken 1934–35 off to study with Ezra Pound at the poet’s “Ezuversity.” Pound counseled Laughlin, “Go back to Haavud to finish up your studies. If you’re a good boy your parents will give you some money and you can bring out books. I’ll write to my friends and get them to provide you with manuscripts.” Pound was right about the money, although Laughlin didn’t wait for the manuscripts to roll in. In 1936, with help from his father and his aunt, he founded New Directions. His first title, New Directions in Prose and Poetry 1936, featured a poem, short story, and essay by William Carlos Williams, whom Laughlin had first published as an editor of the Harvard Advocate. Williams’s White Mule followed in 1937. Pound’s Guide to Kulchur was published in 1938. It would be easy to dismiss Laughlin as a gentleman publisher (Pound invariably did, when frustrated by delays or mistakes), but consider this: New Directions has kept Williams and Pound in print for eighty years. And they are just two poets on a list that includes David Antin, Apollinaire, Baudelaire, Edwin Brock, Ernesto Cardenal, Hayden Carruth, Cid Corman, Gregory Corso, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Richard Eberhart, Russell Edson, William Everson, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, García Lorca, Goethe, H.D., Robinson Jeffers, Bob Kaufman, Irving Layton, Denise Levertov, Michael McClure, Eugenio Montale, Pablo Neruda, Charles Olson, George Oppen, Wilfred Owen, Nicanor Parra, Boris Pasternak, Kenneth Patchen, Octavio Paz, Raymond Queneau, John Crowe Ransom, Raja Rao, Pierre Reverdy, Kenneth Rexroth, Rilke, Rimbaud, Selden Rodman, Jerome Rothenberg, Delmore Schwartz, Stevie Smith, Gary Snyder, Nathaniel Thomas, and Yvor Winters—not to mention Buddha.

— Aaron Fischer, Fort Lee, New Jersey, October 1997

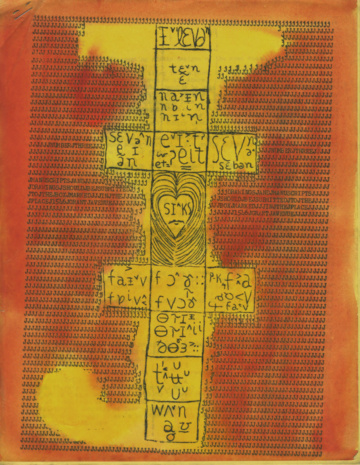

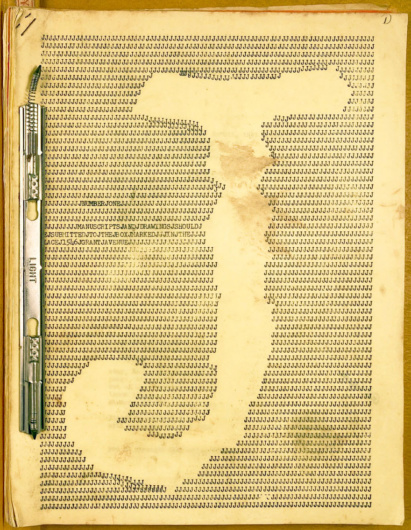

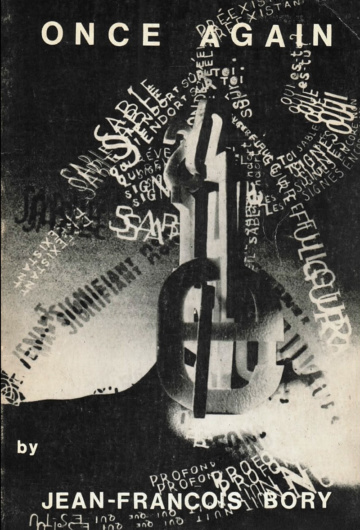

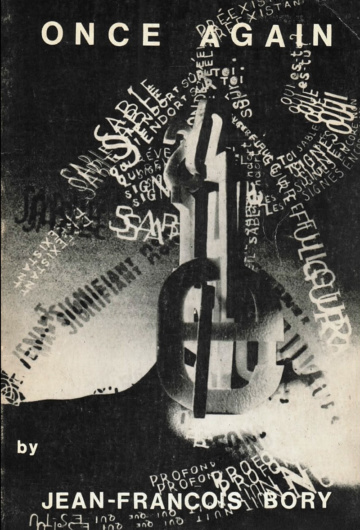

Jean-François Bory, Once Again (1968), translated by Lee Hildreth.

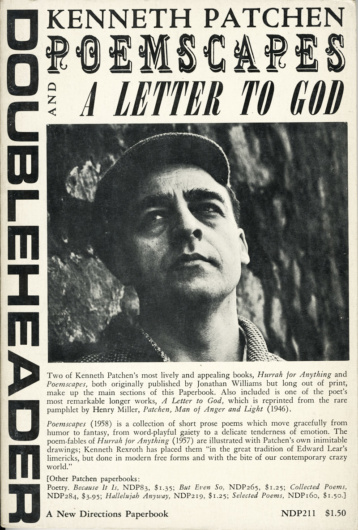

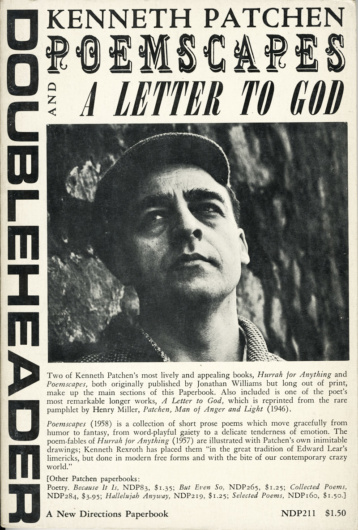

Kenneth Patchen, Poemscapes / A Letter to God (1958).

New Directions books include

Antin, David. talking at the boundaries. 1976.

Bory, Jean-François, ed. Once Again. 1968. Translated by Lee Hildreth.

Corman, Cid. Livingdying. 1970. Cover by Shiryu Morita.

Corman, Cid. Sun Rock Man. 1970.

Corso, Gregory. Elegiac Feelings American. 1970. Cover photograph of the author by Ettore Sottass, Jr.

Corso, Gregory. The Happy Birthday of Death. 1960.

Corso, Gregory. Long Live Man. 1962.

Duncan, Robert. Bending the Bow. 1968. Book and dust jacket designed by Graham Mackintosh. Cover photograph of the author by Nata Piaskowski.

Duncan, Robert. The Opening of the Field. 1973.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. A Coney Island of the Mind. 1958.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. Her. 1960.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. The Secret Meaning of Things. 1968.

Kaufman, Bob. Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness. 1965.

Kerouac, Jack. Excerpt from Visions of Cody. 1959.

Levertov, Denise. The Cold Spring & Other Poems. 1968.

Levertov, Denise. The Collected Earlier Poems. 1979.

Levertov, Denise. Footprints. 1972. Cover photograph by Liebe Coolidge.

Levertov, Denise. The Freeing of the Dust. 1975. Cover photograph of work by Antoni Tàpies.

Levertov, Denise. Life in the Forest. 1978. Cover photograph by Harry Callahan.

Levertov, Denise. O Taste and See. 1964. Cover photograph by Roloff Beny.

Levertov, Denise. The Poet in the World. 1973. Cover photograph of the author’s desk by Suzy Gordon.

Levertov, Denise. The Sorrow Dance. 1966. Cover photograph by Roloff Beny.

Levertov, Denise. With Eyes at the Back of Our Heads. 1959.

McClure, Michael. September Blackberries. 1974.

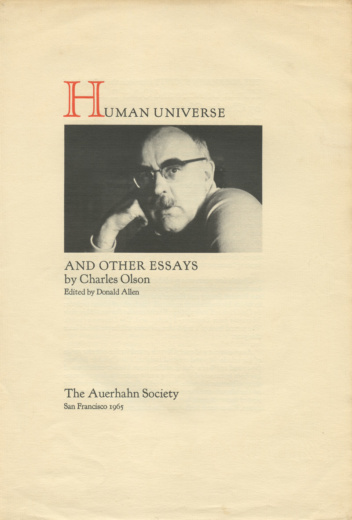

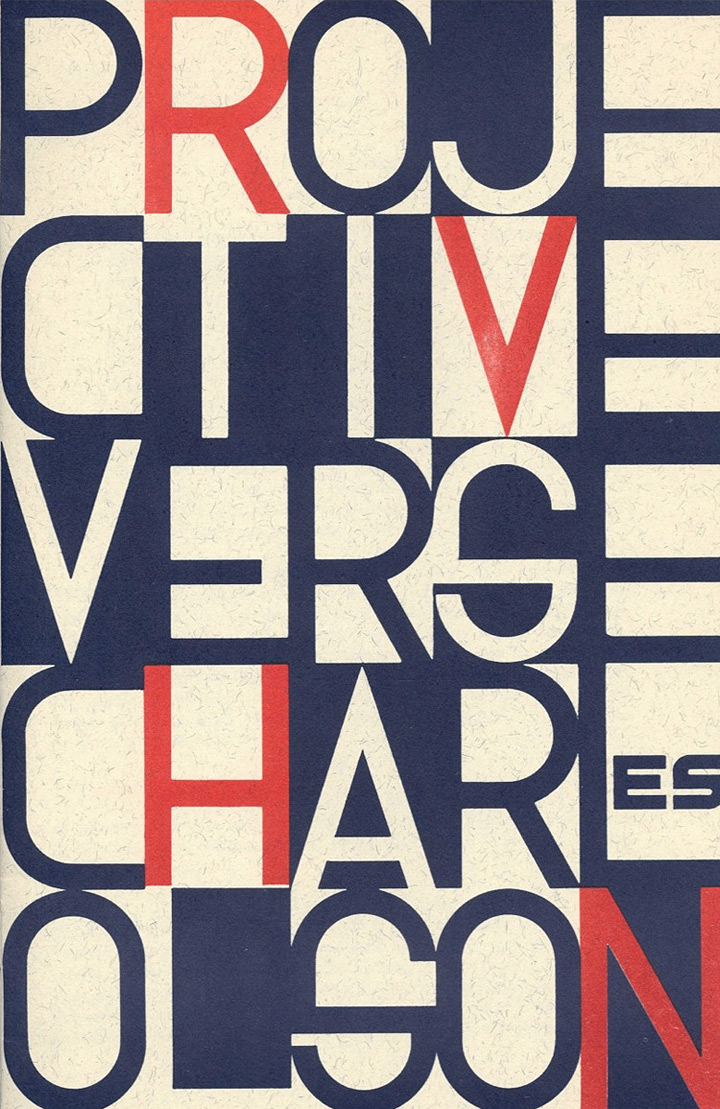

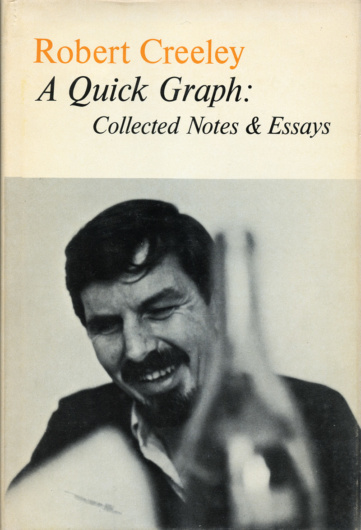

Olson, Charles. Selected Writings. 1966. Edited and with an introduction by Robert Creeley.

Oppen, George. The Collected Poems of George Oppen. 1975.

Oppen, George. The Materials. 1962.

Oppen, George. Of Being Numerous. 1968.

Oppen, George. This in Which. 1965.

Patchen, Kenneth. Because It Is: Poems and Drawings. 1960.

Patchen, Kenneth. But Even So. 1968.

Patchen, Kenneth. Hallelujah Anyway. 1966.

Patchen, Kenneth. In Quest of Candlelighters. 1972.

Patchen, Kenneth. Memoirs of a Shy Pornographer. 1958. Cover photograph of the author by Ray Johnson.

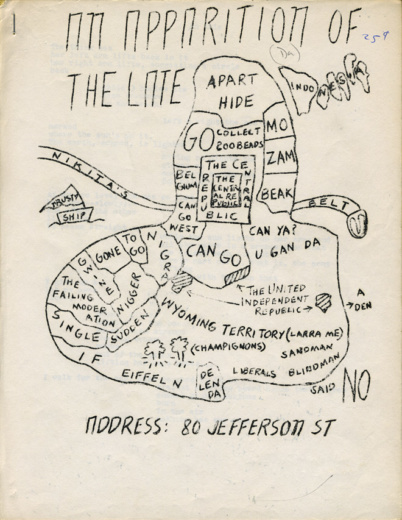

Patchen, Kenneth. Poemscapes / A Letter to God. 1958.

Patchen, Kenneth. Red Wine & Yellow Hair. 1949.

Patchen, Kenneth. Selected Poems. 1957. Cover photograph of the author by Harry Redl. Cover design by David Ford.

Patchen, Kenneth. Sleepers Awake. 1969. Published originally by Padell Books, 1946.

Randall, Margaret. Part of the Solution: Portrait of a Revolutionary. 1973.

Rexroth, Kenneth. The Collected Longer Poems. 1968.

Rexroth, Kenneth. The Collected Shorter Poems. 1966.

Rexroth, Kenneth. Natural Numbers: New and Selected Poems. 1963.

Rexroth, Kenneth, trans. One Hundred Poems from the Chinese. 1965.

Reznikoff, Charles. By the Waters of Manhattan: Selected Verse. 1962. Introduction by C. P. Snow.

Rothenberg, Jerome. Poland/1931. 1974.

Rothenberg, Jerome. Pre-Faces & Other Writings. 1981.

![The Floating Bear 28 [December] 1963. Cover by Alfred Leslie.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/4the-floating-bear_1963_28-405x530.jpg)

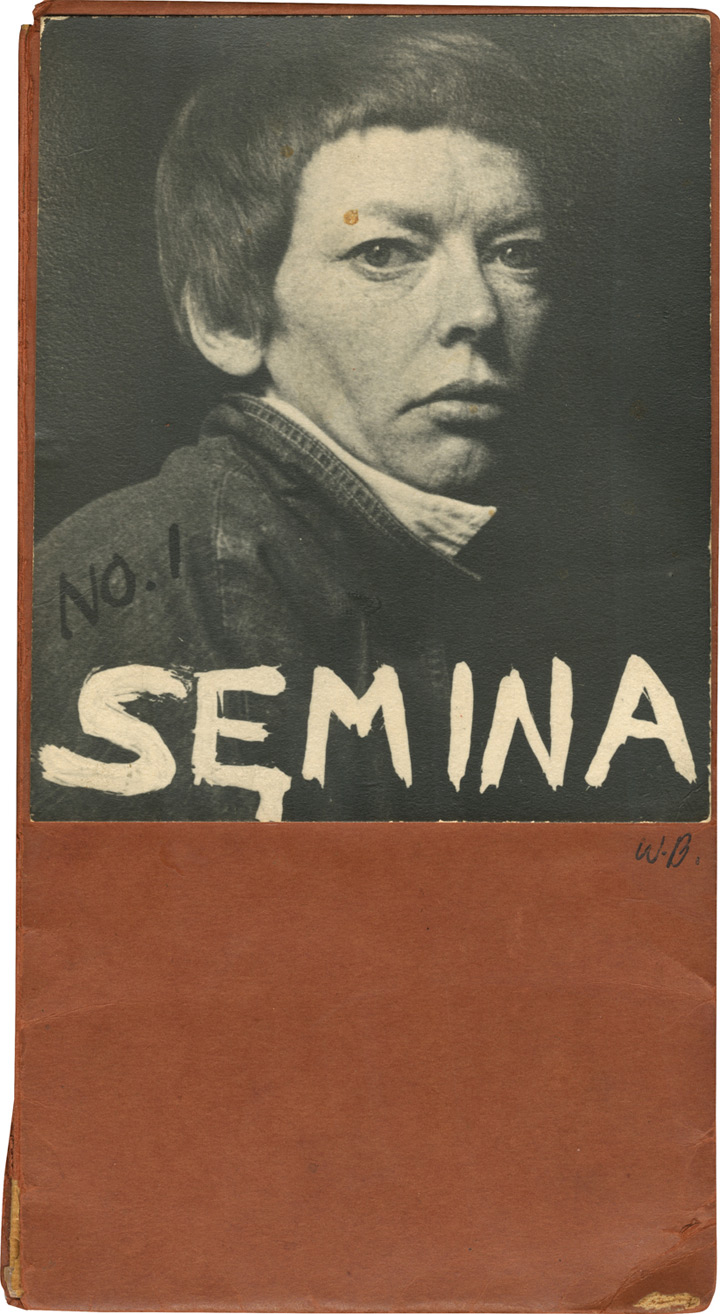

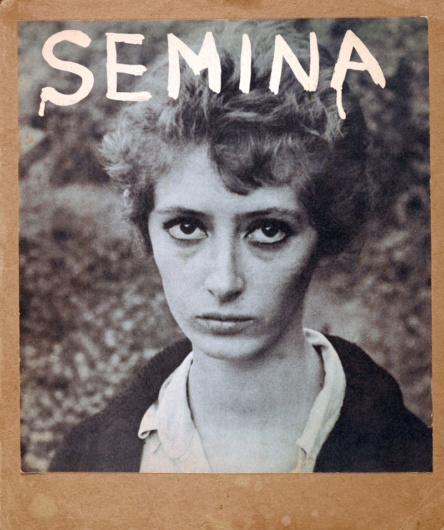

![Floating Bear 37 [March–July] 1969. Cover by Wallace Berman.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-floating-bear_1969_37-1-r-410x530.jpg)

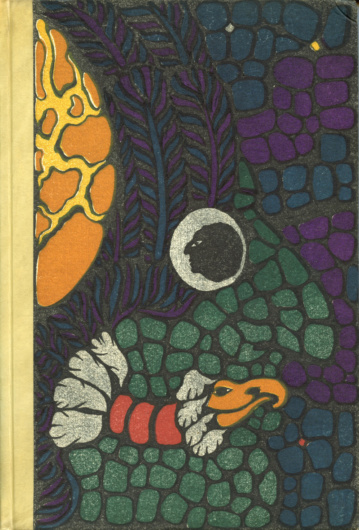

![Jess [Collins], Christian Morgenstern’s Gallowsongs (1970). Illustrations and versions by Jess.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/jess-gallowsongs-black-sparrow-1970-r-400x530.jpg)