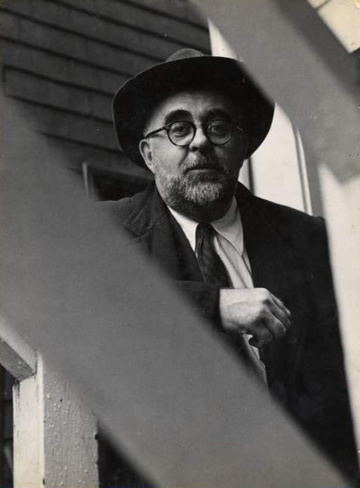

Jonathan Williams describes himself as “a poet, essayist, publisher of the Jargon Society, photographer, occasional hiker of long distances, and aging scold.” Jargon’s first booklet, which contained a poem by Williams with an engraving by David Ruff, was published in San Francisco in 1951. The press blossomed at Black Mountain College where its peripatetic director moved to study photography with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. Jargon’s second publication was a poem by Joel Oppenheimer (“The Dancer”) with a drawing by Robert Rauschenberg. Over the next several years the press would publish Kenneth Patchen, Robert Creeley, The Maximus Poems by Charles Olson, more work by Williams, Louis Zukofsky, Denise Levertov, Michael McClure, Mina Loy, Robert Duncan, Fielding Dawson, Irving Layton, Guy Davenport, Paul Metcalf—the list goes on and on.

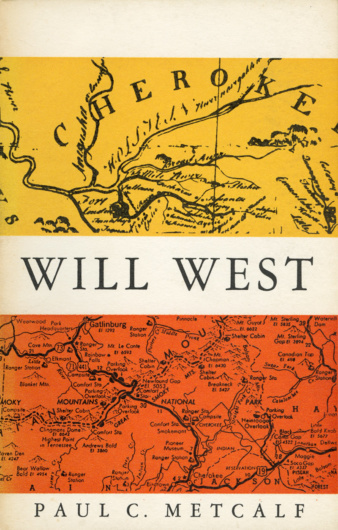

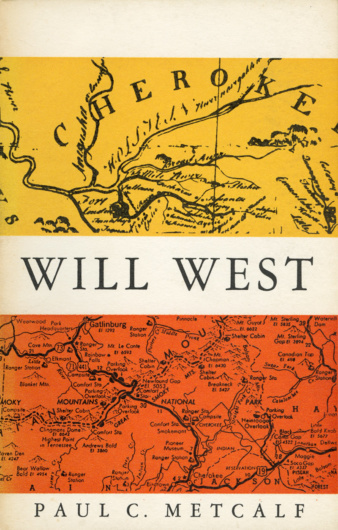

Paul C. Metcalf, Will West (1956). Jargon 25.

The Jargon Society married excellence in the art of book-making with important writing, to become what critic Hugh Kenner aptly called “the custodian of snowflakes.” When asked why he has published what he has, Williams replied, “For pleasure surely. I am a stubborn, mountaineer Celt with an orphic, priapic, sybaritic streak that must have come to me, along with H. P. Lovecraft, from Outer Cosmic Infinity. Or maybe Flash Gordon brought it from Mongo? Jargon has allowed me to fill my shelves with books I cared for as passionately as I cared for the beloved books of childhood—which I still have: Oz, The Hobbit, The Wind in the Willows, Dr. Doolittle, Ransome, Kipling, et al.”

Larry Eigner, On My Eyes (1960). Jargon 36. Photographs by Harry Callahan. Introduction by Denise Levertov.

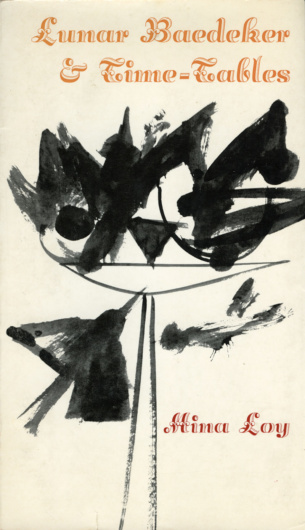

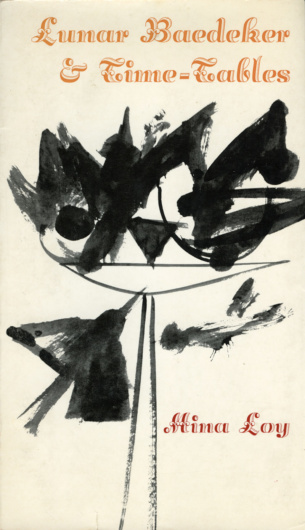

Mina Loy, Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables (1958). Jargon 23.

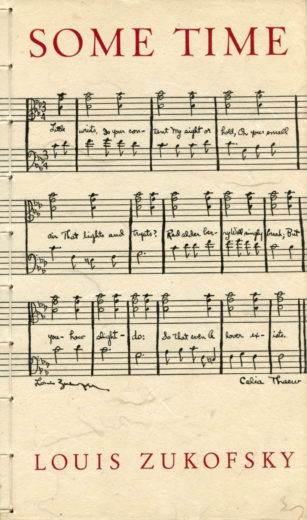

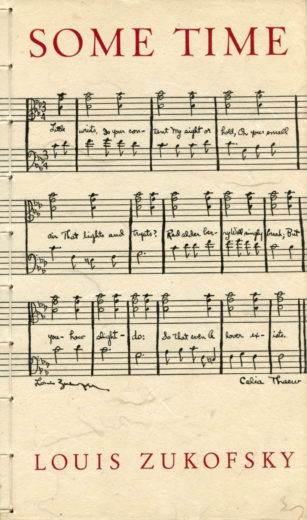

Louis Zukofsky, Some TIme: Short Poems (1956). Jargon 15. Cover image is a song setting by Celia Zukofsky.

Jargon Society books include

Broughton, James. A Long Undressing: Collected Poems 1949–1969. 1971. Jargon 55. Cover photograph by Imogen Cunningham.

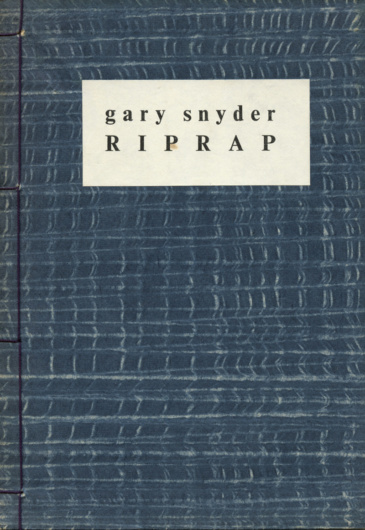

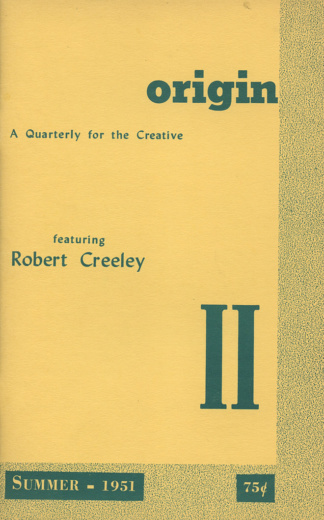

Creeley, Robert. All That Is Lovely in Men. 1955. Jargon 10. Drawings by Dan Rice.

Creeley, Robert. The Immoral Proposition. 1953. Jargon 8. Drawings by René Laubiès.

Davenport, Guy. Do You Have a Poem Book on E. E. Cummings. 1969. Jargon 67.

Davenport, Guy. Flowers and Leaves. 1966. Jargon 46. Cover photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard.

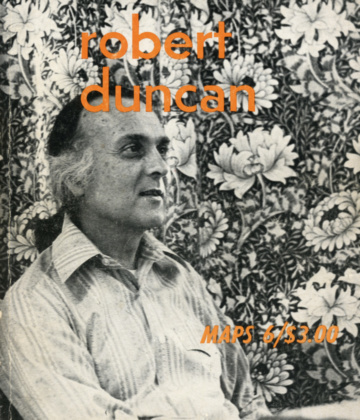

Duncan, Robert. Letters: Poems mcmliii–mcmlvi. 1958. Jargon 14. Drawings by the author.

Eigner, Larry. On My Eyes. 1960. Jargon 36. Note by Denise Levertov. Photographs by Harry Callahan.

Johnson, Ronald. A Line of Poetry, a Row of Trees. Drawings by Thomas George. 1964. Jargon 42. Drawings by Thomas George.

Johnson, Ronald. The Spirit Walks, the Rocks Will Talk: Eccentric Translations from Two Eccentrics. 1969. Jargon 72. Vignettes by Guy Davenport.

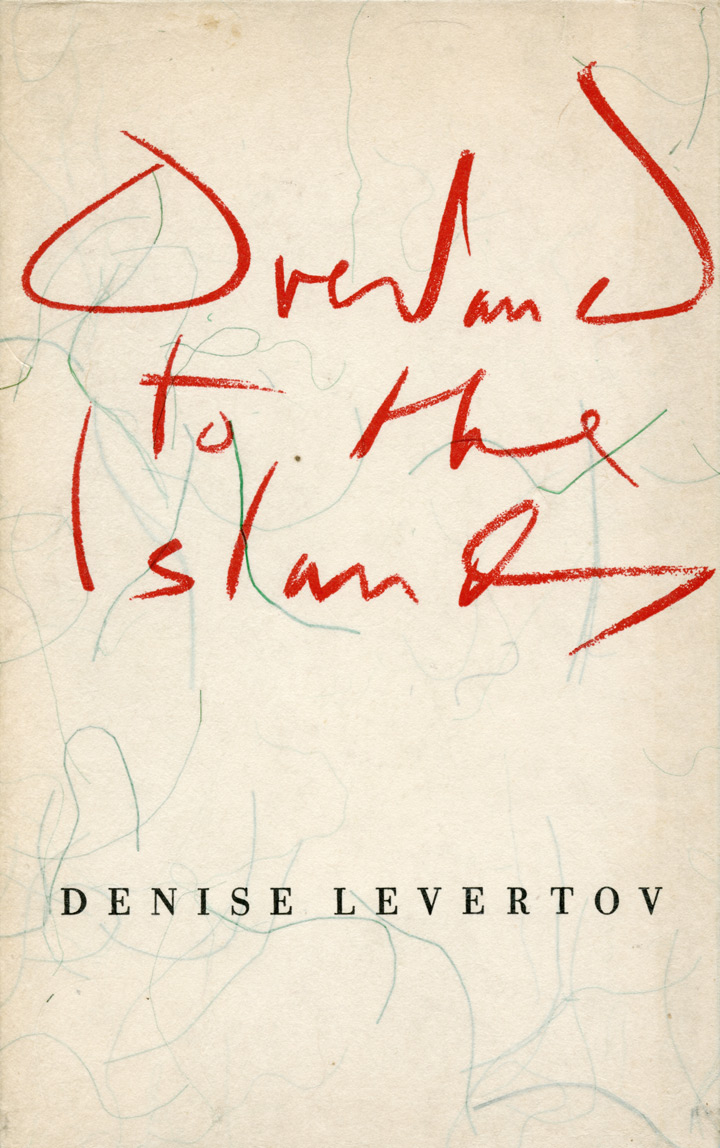

Levertov, Denise. Overland to the Islands. 1958. Jargon 19.

Loy, Mina. Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables: Selected Poems. 1958. Jargon 23. Introductions by William Carlos Williams, Kenneth Rexroth, and Denise Levertov. Drawings by Emerson Woelffer.

McClure, Michael. Passage. 1956. Jargon 20. Cover by Jonathan Williams.

Niedecker, Lorine. T & G: The Collected Poems. 1968. Jargon 48. Plant prints by A. Doyle Moore.

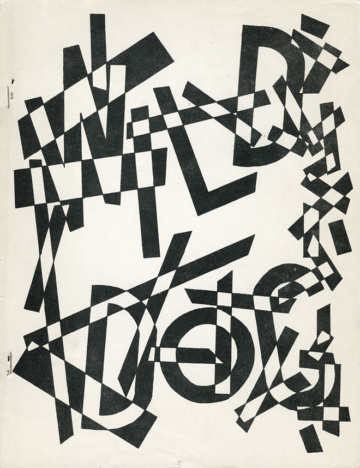

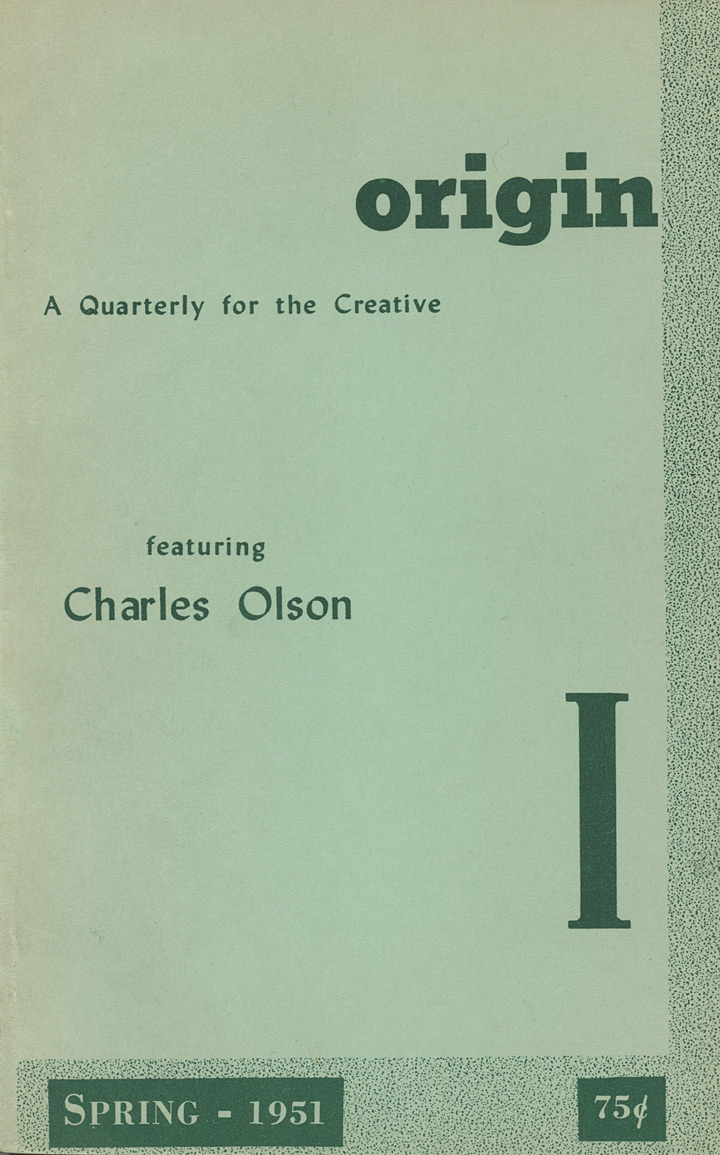

Olson, Charles. Maximus 1–10. 1953. Jargon 7. Calligraphy by Jonathan Williams.

Olson, Charles. Maximus 11–22. 1956. Jargon 9. Calligraphy by Jonathan Williams.

Oppenheimer, Joel. The Dancer. 1951. Jargon 2. Drawing by Robert Rauschenberg.

Oppenheimer, Joel. The Dutiful Son. 1956. Jargon 16.

Patchen, Kenneth. Fables and Other Little Tales. 1953. Jargon 6.

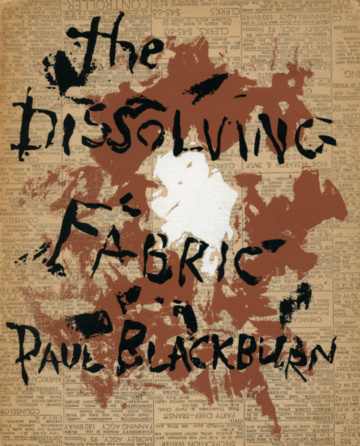

Sorrentino, Gilbert. The Darkness Surrounds Us. 1960. (Not in series.) Cover by Fielding Dawson.

Williams, Jonathan. Garbage Litters the Iron Face of the Sun’s Child. 1951. Jargon 1.

Williams, Jonathan. Red/Gray. 1952. Jargon 3. Drawings and declaration by Paul Ellsworth.

Zukofsky, Louis. Some Time: Short Poems. 1956. Jargon 15.

Continue readingClose

Jargon also published the following, in association with Corinth Books:

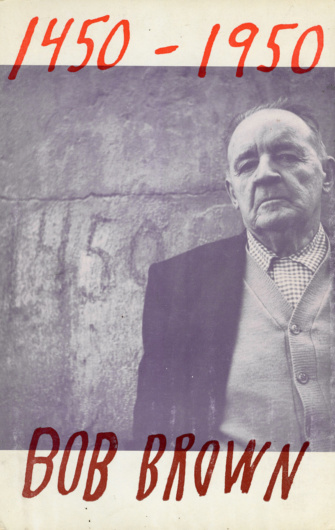

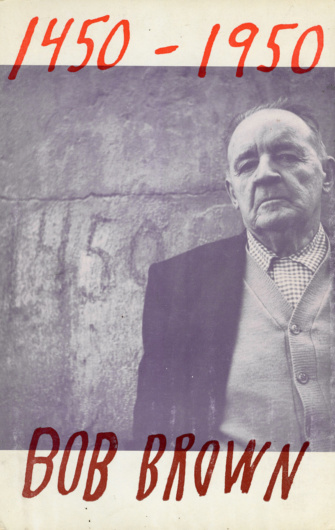

Brown, Bob. 1450–1950. 1959. Jargon 29.

Bob Brown, 1450–1950 (1959). Jargon 29. Published in association with Corinth Books. Cover photograph by Jonathan Williams.

Creeley, Robert. A Form of Women. 1959. Jargon 33. Photograph by Robert Schiller.

Olson, Charles. The Maximus Poems. 1960.

Zukofsky, Louis. A Test of Poetry. 1964. Originally published in 1948 by the Objectivist Press.

Resource

For a more complete listing of the early Jargon publications, the reader is referred to: Millicent Bell, “The Jargon Idea,” Books at Brown 19 (May 1963, reprinted separately, 1963); and to J. M. Edelstein, A Jargon Society Checklist 1951–1979, published in conjunction with an exhibition of Jargon publications at Books & Co., New York City, March 15–April 14, 1979.

![Detroit Artists Workshop Benefit: Seven Poets, Santa Fe-Albuquerque. Captain Mimeo and the Pepsi Shooter Press Book no. 1. [Duende Press], March 11, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/detroit-family-r-407x530.jpg)

![Wolf Vostell, and Dick Higgins, eds. Fantastic Architecture [1970 or 1971]. Book jacket illustration: Richard Hamilton’s Guggenheim Collage, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vostell-architecture-r-360x498.jpg)

![Maps 1 [1966]. Cover: Herbert Bayer, “Graphic Fragment #2.”](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/maps-1-r-599x530.jpg)

![Maps 3 [1970]: Poems for John Coltrane. Cover by Roger Shimomura.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/MAPS-no-3-1970-r-455x530.jpg)

![Charles Olson, Mayan Letters (1953 [i.e., 1954].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/charles-olson-mayan-letters-divers-press-r-409x530.jpg)