Scarlet

Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver

New York City

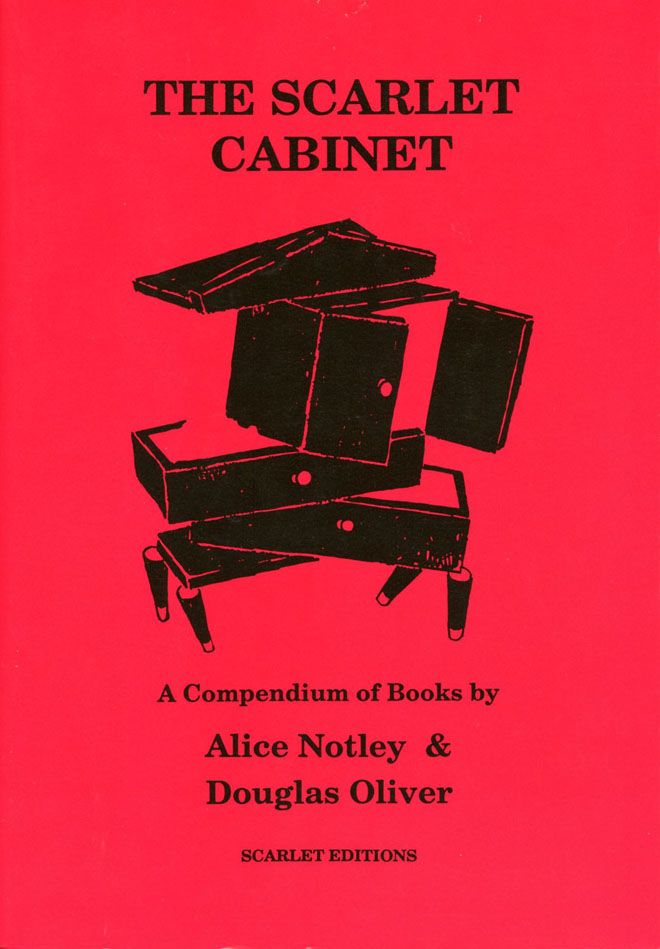

Nos. 1–5 (Sept. 1990–Sept.1991), and nos. 6–8 published as The Scarlet Cabinet: A Compendium of Books by Alice Notley & Douglas Oliver (Mar. 1992).

Scarlet, no. 1. Sept. 1990.

Published out of Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver’s apartment at 101 St. Mark’s Place in New York City in five issues from 1990 to 1991, Scarlet defiantly embraced a mixture of experimentation, politics, and obsolescence. As they state in the inaugural issue’s editorial, “Editorials in this kind of newspaper being out of fashion, that’s the first point. We don’t much like the fashion in poetry/literary magazines which aims for wimpish purity of text: too boring.” Driven by the call to “be guided by right spirit,” a tacit reference to the political party “Spirit” founded by Will Penniless and friends in Oliver’s Penniless Politics, Scarlet’s “emphasis will be upon that spirit in a work which unites vision to concern—whether political, social, personal, or fantastical.”

Publishing writers associated with the afterlives of the New American Poetry, especially New Cambridge and New York School poets, as well as younger writers influenced by these lineages, Scarlet includes work by Anselm Hollo, Amiri Baraka, Barbara Guest, Pierre Joris, Denise Riley, Susie Timmons, Elio Schneeman, Eileen Myles, and many others, as well as artwork by Joe Brainard, Rudy Burckhardt, Yvonne Jacquette, and George Schneeman. Notable contributions include the earliest publication of excerpts from Notley’s The Descent of Alette, then identified as “An Untitled Long Poem”; a regular “Dream Gossip” column; a fiery set of editorials; Steve Abbott’s “A house on fire” article about the ongoing AIDS crisis; and Notley’s essays “Women & Poetry” and “What Can Be Learned From Dreams?”

The column-based “newspaper” format of Scarlet, similar to both The Poetry Project Newsletter and Kathleen Fraser’s HOW(ever), creates a non-linear, generative reading experience, as works in different genres and of different lengths extend over multiple pages in a variety of columns, side-bars, and sections, producing a visual-textual arrangement that sparks convergences of voices and ideas. For example, in Scarlet no. 2, a conversation between Leslie Scalapino and Philip Whalen extends over four pages alongside a section from The Descent of Alette, a convergence that places Whalen’s humorously disparaging description of Charles Olson’s “Projective Verse,” what he calls “that God-awful essay that everyone just loves to death,” alongside a section of Notley’s feminist epic that up-ends Olson’s masculine-civic founding of a new poetics of the syllable and the line.

In a 1997 autobiographical essay, Oliver remarks on the origins and work of Scarlet:

Alice had been working on several poem sequences, including her now-celebrated The Descent of Alette. I had a Robert Louis Stevenson pastiche ready—Sophia Scarlett, a feminist version of a novel Stevenson had projected before his death. And we had begun a newspaper-style poetry magazine, Scarlet. It was Gulf War time, so we had plenty to editorialize—and agonize—about; Alice ran a ‘Dream Gossip’ column, which printed everyone’s scandalous dreams; Anselm Hollo had a regular filler feature of aperçus called Hollograms; and we were called one of the brightest new small poetry reviews for a while. We serialized The Descent of Alette and Penniless Politics and our final issue was a fat book, called, to continue our scarlet thematics, The Scarlet Cabinet.

Published in March 1992 as three-issues-in-one, The Scarlet Cabinet: A Compendium of Books by Alice Notley & Douglas Oliver contains three works by Oliver—Penniless Politics, Sophia Scarlett, and Nava Sūtra—and four works by Notley—The Descent of Alette, Beginning With A Stain, Twelve Poems Without Mask, and Homer’s Art. Framed as an act of resistance against conservative aesthetics and a homogenous publishing industry, the aim of work in The Scarlet Cabinet was to, as Notley writes, “pay attention to the real spiritual needs of both her neighbors (not her poetic peers) & the future.” As Oliver writes in his introduction:

Why not, we thought, publish a book rather like a chance collection of Medieval manuscripts bound into one volume, a book which thumbs its nose at all this? We only care about the spirit of what we write anyway: we don’t care about the business-suited poetic world, or the NEA – any of that. So why not have some fun?

— Nick Sturm, Atlanta, May 2021

Scarlet, no. 2. Fall 1990.

Scarlet, no. 3. Winter 1991.

Scarlet, no. 4. Spring 1991.

Scarlet, no. 5. Sept. 1991.

The Scarlet Cabinet: A Compendium of Books by Alice Notley & Douglas Oliver. Scarlet Editions, 1992.