Chicago

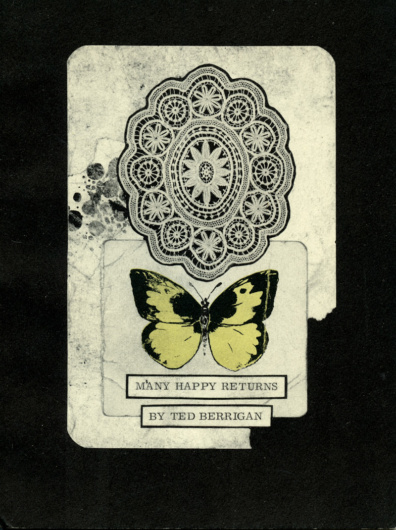

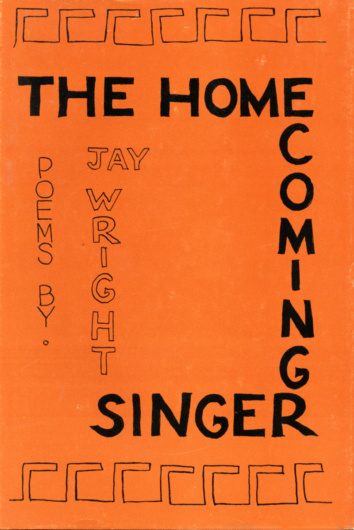

Alice Notley

Chicago and Wivenhoe, Essex, UK

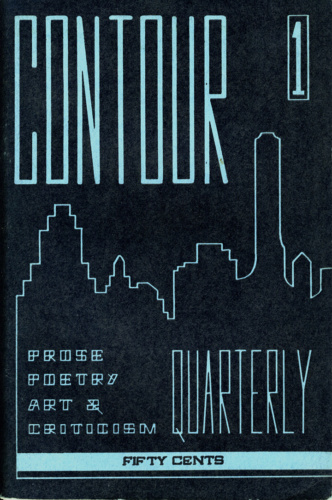

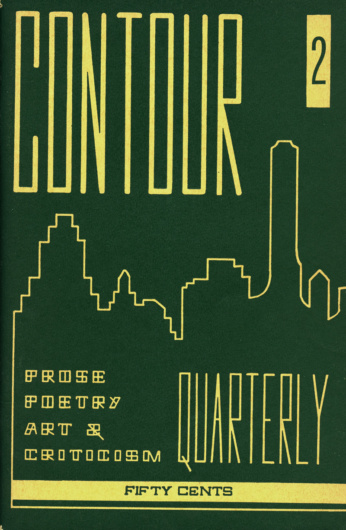

Six issues published in Chicago (Feb. 1972–Mar. 1973) from vol. 1, no. 1, to vol. 6. See image captions below for complete enumeration.

Three issues published as “European Edition,” nos. 1–3 in Wivenhoe, Essex, UK (Oct. 1973–June 1974).

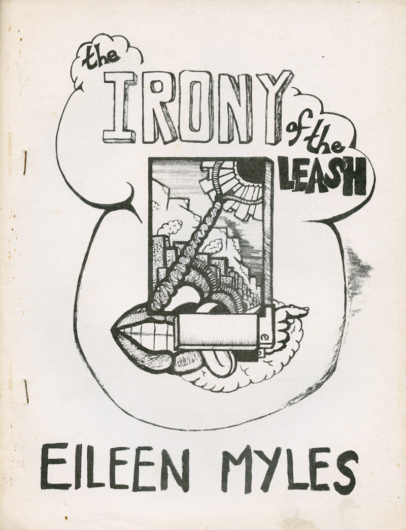

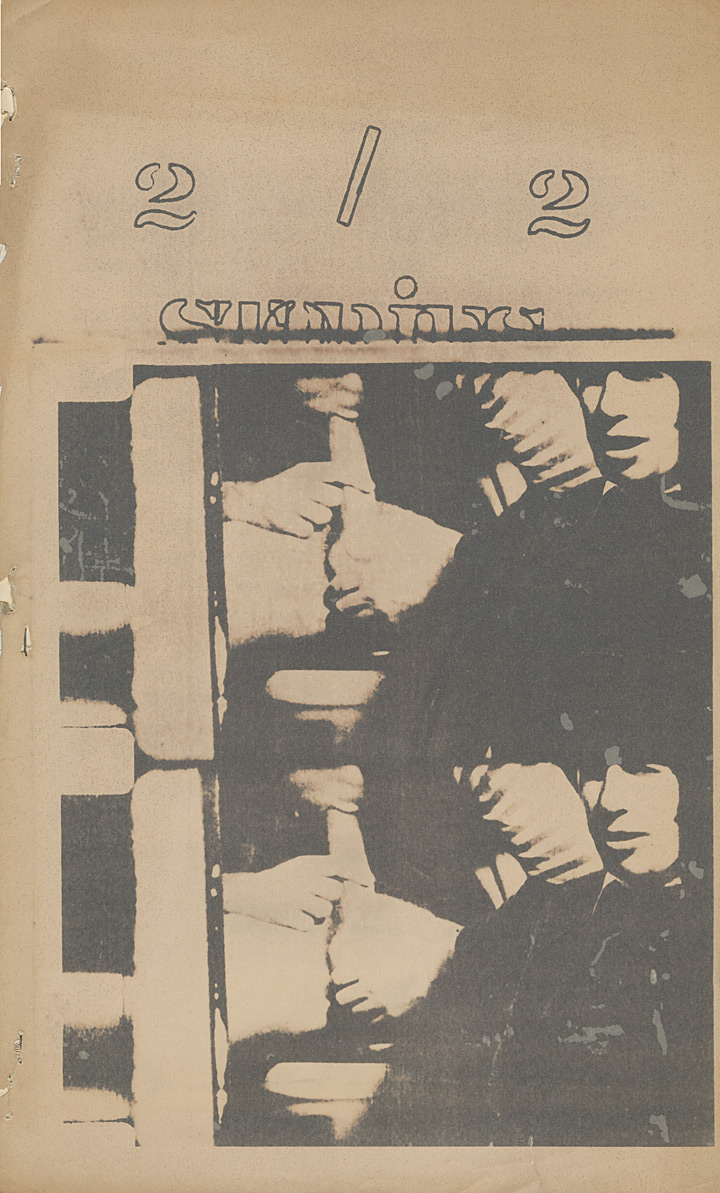

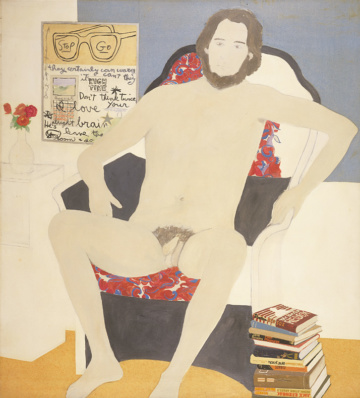

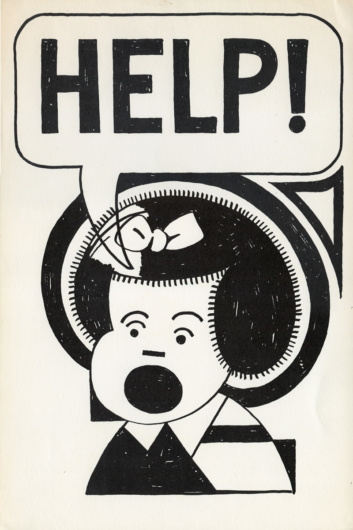

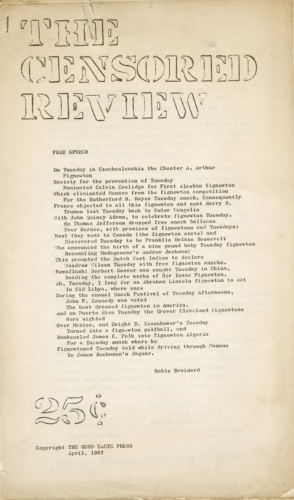

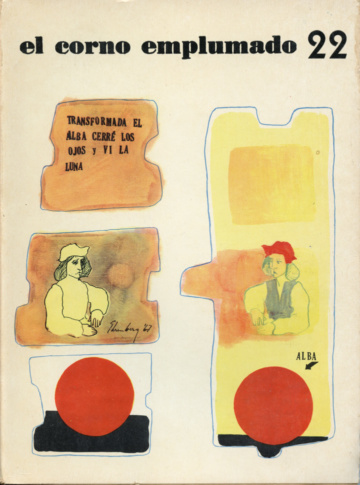

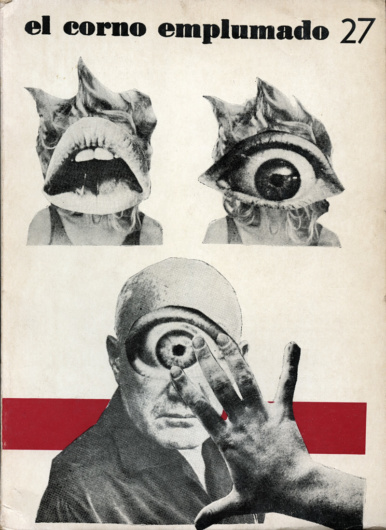

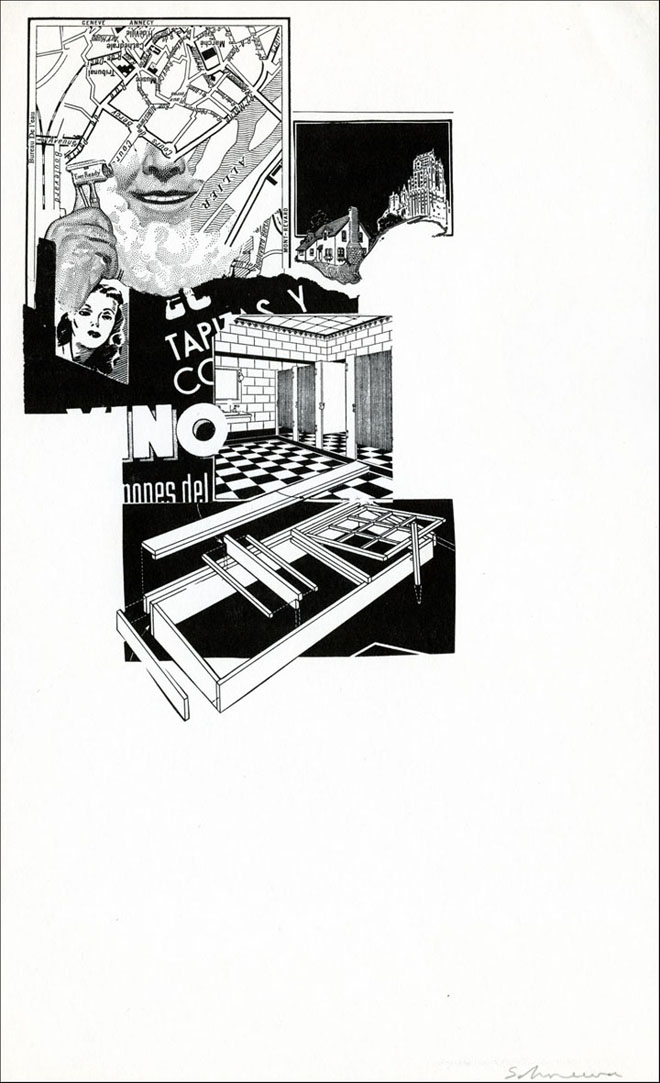

All covers by George Schneeman.

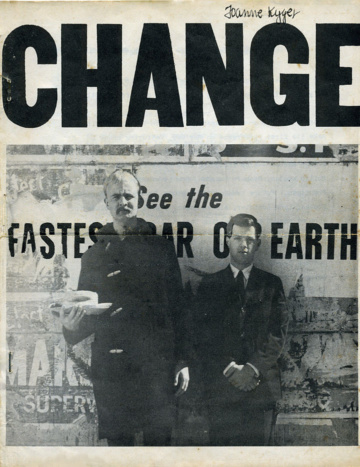

Chicago, vol. 1, no. 1. Feb. 1972.

CHICAGO is one of the most important mimeograph magazines of the 1970s, not only for being edited by Alice Notley during the beginning of her career but also for how it traces the movement of New York School-style poetics between the Midwest and England. Published shortly after her graduation from the Iowa Writers Workshop and marriage to Ted Berrigan, a time when, as Notley writes, “I was in danger—I saw it that way—of not becoming a poet,” Chicago offered a publishing context in which to maintain a necessary autonomy as a woman and artist and to trace her own sense of overlapping aesthetic lineages as she, Berrigan, and their children followed a migratory teaching circuit. As poet and scholar Stephanie Anderson writes in Mimeo Mimeo No. 5 (Fall 2011), “For Notley, the magazine becomes a way to keep the participants of various geographically scattered communities in communication.”

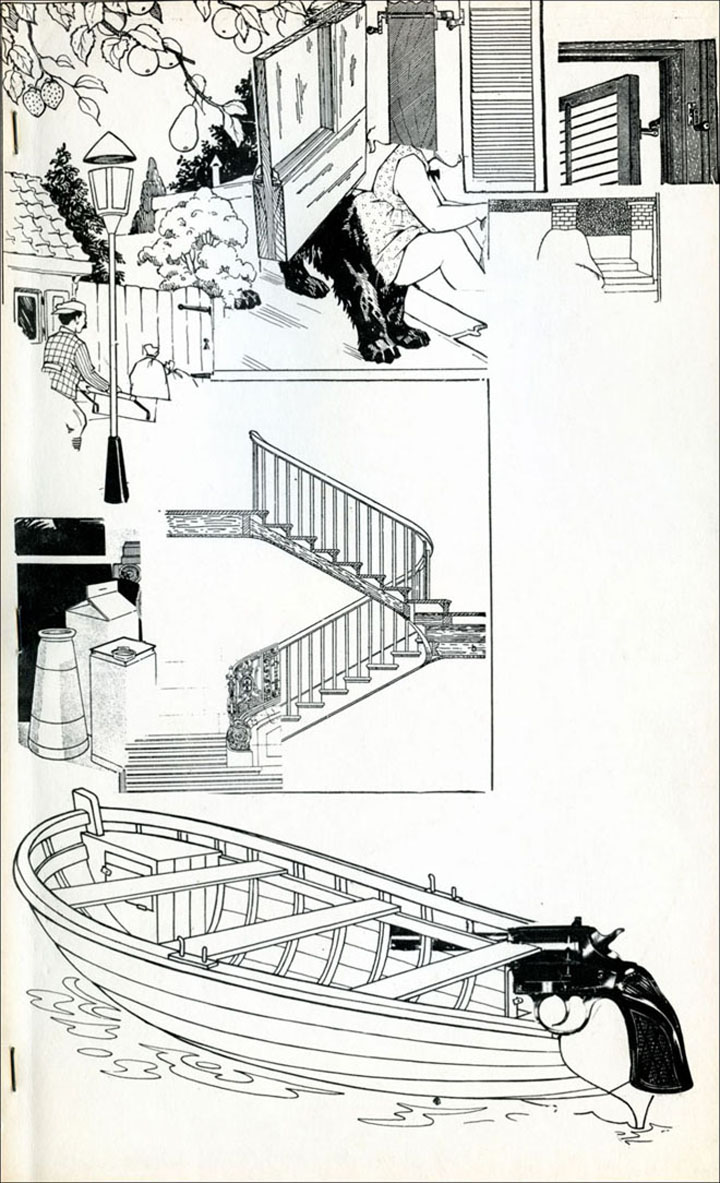

Characterized by Notley’s interest in publishing large collections of poems by individual writers, sometimes over 20 poems, and an art gallery-like approach to how pieces sit on the page, Chicago is a record of the aesthetic experimentation and associations in the early 1970s that bend outside standard narratives of the New York School. It is also a record of Notley’s establishment of her editorial vision that would extend into the editing of Scarlet and Gare du Nord with Douglas Oliver. The magazine’s run of nine issues is composed of two distinct publishing formats: six legal-size mimeographed issues published in Chicago, with the fifth issue guest-edited by Berrigan, followed by three 8.5 x 11 in. mimeographed “European Editions” published in Wivenhoe while Berrigan was teaching at the University of Essex in Colchester. Poets such Tom Clark and Ed Dorn had previously taught at Essex, making the small riverside town of Wivenhoe—Doug Oliver called it the “campus village”—an unlikely but vital outpost in the transnational networks of American avant-garde poetry. As Berrigan wrote jokingly to Bill Berkson soon after he began teaching at Essex, “Wivenhoe is enrolling en masse in the 2nd (3rd?) Generation NY School, as you must know by now.” Notley and Berrigan befriended poets such as Pierre Joris, Gordon Brotherston, Ralph Hawkins, Charlie Ingham, Simon Pettet, and Doug Oliver during their time in England, the latter four of whom edited the magazine The Human Handkerchief from 1973–1975.

George Schneeman contributed cover art to all nine issues of Chicago, including a series of interconnected collage covers for the first six issues that offer a stunning visual unity to the magazine. Berrigan handled mimeographing, but Notley was completely in control of the rest of the magazine. Recalling the process of assembling the early issues, Notley notes, “I remember collating right before I gave birth to Anselm, just having all of the pages spread throughout the room and walking around pregnantly and collating everything and doing all the writing.” Highlights from throughout the magazine include poems by Lorenzo Thomas, Bill Berkson, Bernadette Mayer, Clark Coolidge, Maureen Owen, Joe Ceravolo, and F.T. Prince, textual-visual work by Philip Whalen, Joe Brainard’s comic strip collaborations with John Ashbery and Kenneth Koch, over 50 pieces by Notley herself, Ron Padgett’s translation of “Zone” by Guillaume Apollinaire, Anne Waldman’s 1964 “From the Egypt Journal” documenting a trip to Egypt with Brainard, and a conversation between George Oppen, Mary Oppen, and Berrigan arranged by Ruth Gruber. Poems by Berrigan’s students at Iowa and Chicago also appear, including work by George Mattingly, Neil Hackman, Henry Kanabus, Merrill Gilfillan, Art Lange, and Richard Friedman.

— Nick Sturm, Atlanta, May 2021

Chicago, European Edition, no. 2. Feb. 1974.

Chicago, European Edition, no. 3. June 1974.

Chicago, vol. 2, no. 2/3. Mar.–Apr. 1972.

Chicago, vol. 3, no. 4/5. May 1972.

Chicago, vol. 4, no. 6. Summer 1972. Cover only.

Chicago, vol. 5, no. 1. Nov. 1972.

Chicago, vol. 6. Mar. 1973.

Chicago, European Edition no. 1. Oct. 1973.