Search for Tomorrow

George Mattingly

Iowa City

Nos. 1–4/5 (1970–72).

Plus Special Number A, Something Swims Out by Darrell Gray. No. 6, a set of 24 4 x 6-inch postcards, was announced but not completed.

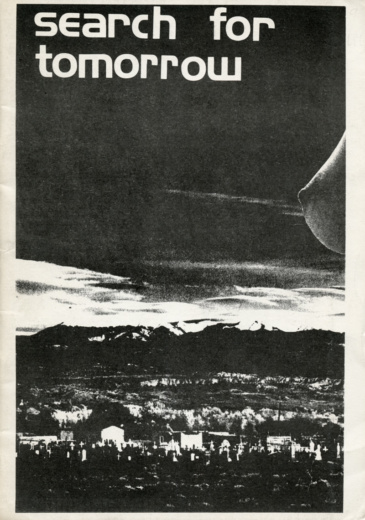

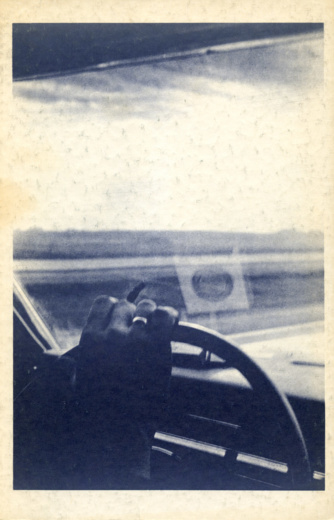

Search for Tomorrow 1 (1970). Cover by George Mattingly.

A Short History of Search for Tomorrow, 1969–1973

I moved to Iowa City in autumn 1968, drawn by the university’s Writers Workshop. There I met lifelong friends Darrell Gray, Merrill Gilfillan, and Marc Harding, and later teachers (who also became lifelong friends) Ted Berrigan, Anselm Hollo, and Jack Marshall, among many others in what was an action-packed avant-garde literary, film, art, and music scene centered around the University of Iowa—whose academic authority the scene actively fought. (Irony and head-on contradiction were little barrier in 1968.) Did I forget sex drugs and rock & roll? It barely resembled “Iowa.”

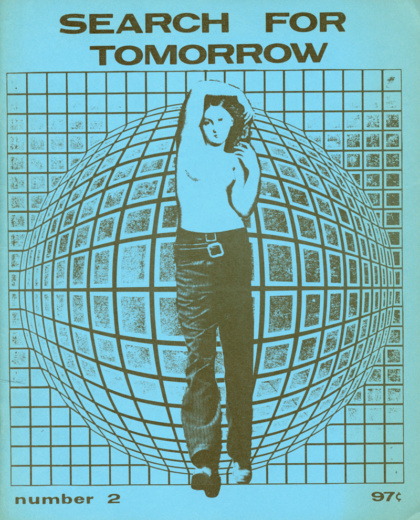

Search for Tomorrow 2 (1971). Cover by George Mattingly.

In 1969, encouraged by photographer and writer Tim Hildebrand, with visual artist Deborah Owen, I started Search for Tomorrow (stealing the name from the hit TV soap opera), determined to leave no boundary uncrossed, no element of the culture too sacred or too banal to be fed to the surrealist engine of poetry and visual art I wanted to create.

The look and feel I sought was neither the staid, visually deprived authority of the academic literary journals nor the minimal mimeo esthetic of the “underground” little magazines. My idea (however naive it might seem in hindsight) was that a wider audience could be reached if the magazine had a richer, juicier surface. I wanted Search for Tomorrow to interest not just the In Crowd, not just those already in love with contemporary literature.

I was also determined that the publication not take itself too seriously. Sometimes this determination drifted off the reservation and risked seeming to not take the work itself seriously enough (that was the danger), but at the time it seemed most important to avoid the academics’ stentorian Voice of Authority.

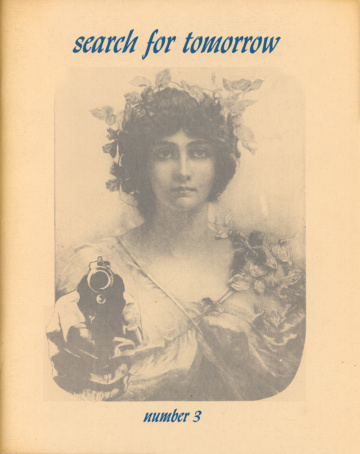

Search for Tomorrow 3 (1970). Cover by George Mattingly. The cover was printed on four different colored stocks.

Publishing technology evolved quickly in the late sixties. The spread of inexpensive photocopying and falling prices for small-format offset presswork made it possible to reproduce anything that could be photographed. Search for Tomorrow took every advantage of that. Anything that could be pasted up on a flat sheet became camera copy: typescripts, found art cut from magazines and newspapers, cereal box art, line drawings, etchings from old magazines and books, even small objects. It was fun, but also took heat. (Years later when Blue Wind Press published Ted Berrigan’s selected poems, So Going Around Cities, he made me promise to “not put any fucking grandfather clocks on the pages.”)

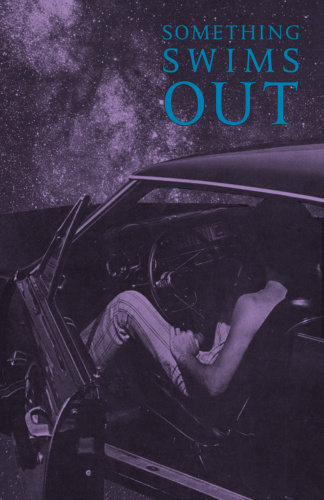

Over four years I published a mix of midwestern, New York School, and over-the-transom poets, artists, and prose writers, some well known, most not. I became more interested in publishing books. Darrell Gray’s first book of poetry, Something Swims Out, was published as a Search for Tomorrow “special issue.” Then, after a move to Vermont (where I was hired as book designer for Dick Higgins at Something Else Press), the magazine was done.

— George Mattingly, Berkeley, March 2017

Darrell Gray, Something Swims Out (Blue Wind Press, 1972). Issued as Search for Tomorrow Special Number A. Cover by George Mattingly.

Search for Tomorrow 4/5 (Spring 1972). Front cover by Allan Kornblum.