whe’re

Ron Caplan and John Sinclair

Detroit

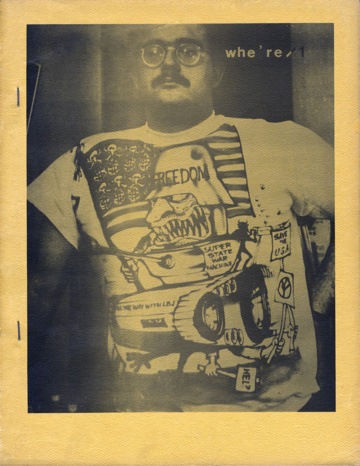

whe’re 1 (Summer 1966). Sole issue.

Page 96 of the magazine Work, no. 3 announces:

Magazine editors note: we will be starting a new magazine soon, called whe’re, which will be concerned with gathering & presenting all possible news of magazine & little presses’ activity, both current & what will happen in the next few mo[n]ths. Like advertising free of charge, & in depth.

In the announcement the editors are listed as Ron Caplan, Robin Eichele, and John Sinclair; the first issue was to appear in April [1966], along with Work, no. 4, “& simultaneously thereafter.”

whe’re no. 1 (the only issue) appeared in the summer of 1966, by which time Sinclair was serving a six-month sentence in the Detroit House of Corrections following his second conviction for marijuana possession. Kaplan was listed as editor and Sinclair as contributing editor.

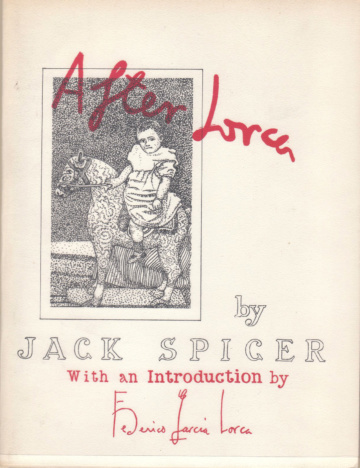

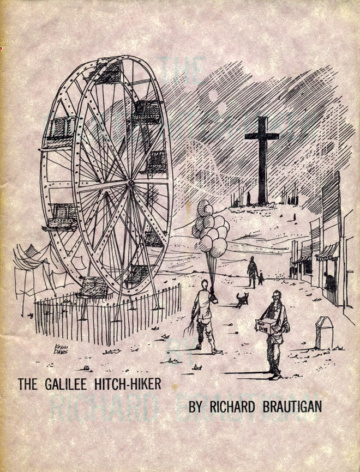

The issue begins with “The Trial of Mamachtaga, a Delaware Indian, the First Person Convicted of Murder West of the Alleghany Mountains, and Hanged for His Crime” by Judge H. H. Brackenridge and continues with poems and notes on presses, magazines, and publications by Victor Coleman, Jonathan Williams, Gino Clays, Margaret Randall, Donald Allen, Andrew Crozier, Douglas Casement, T. David Horton, Artists’ Workshop, Stan Persky, and Jack Spicer.

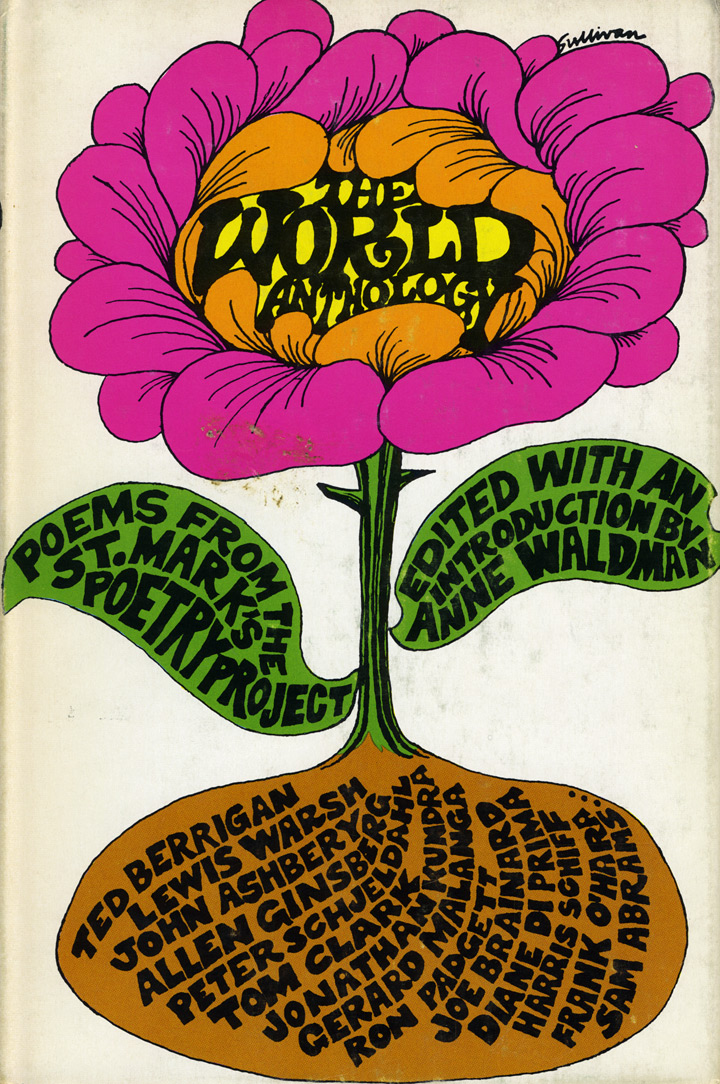

There is a section on Haniel Long with contributors Ed Dorn, Henry Miller, Haniel Long, Howard McCord, and Lawrence Clark Powell; an interview with Robert Creeley by John Sinclair and Robin Eichele; a Robert Creeley Bibliography by Stephen Rodefer; an Index to Kulchur 1–20 by Rosalind Kass; and “rev-yous” including Malay Roy Choudhury on Subimal Basak (both members of the Hungry Generation; in December 1965 Choudhury would be convicted of obscenity in Calcutta), David Sinclair (John’s brother) on Max Finstein, Bill Hutton on the New Rand McNally World Pocket Atlas, David Franks on Robert Creeley, Jerry Younkins on Lew Welch and “The Free Poets,” George Tysh on Gary Snyder and Richard Duerden, Thomas Clark on Sam Abram, Andrew Crozier on George Stanley, Ron Caplan on Larry Goodell/Duende, John Sinclair on William S. Burroughs and LeRoi Jones (dateline Detroit House of Correction May 22, 23, 1966).

Details

whe’re was printed at the Artists’ Workshop Press. The cover photograph of John Sinclair (wearing a sweatshirt custom made by Stanley Mouse) and the interior photograph of Robert Creeley (p. 47) were taken by Magdalene [Leni] Sinclair in 1965.

The issue pictured above contains two inserts:

1) “Artists’ Workshop Press Current Catalog” listing Work, nos. 2, 3; Change nos. 1, 2; whe’re, no. 1; “Workshop Books: first books by Detroit poets & writers” including George Tysh, John Sinclair, J. D. Whitney, Jim Semark, Jerry Younkins, Free Poems/Among Friends, vols. 1, 2, and The Fugs Songbook! (reprinted from the Fug Press edition). [8½ x 11 inches, folded]

2) A printed note from John Sinclair welcoming subscriptions and donations to the Artists’ Workshop Press. [8½ x 4 inches]

![The World 39 [1983?].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-world-no-39-1983-r-360x467.jpg)