Vagabond

John Bennett

Munich; San Francisco; Redwood City, California; and later Ellensburg, Washington

Nos. 1–31 (1966–79).

Nos. 1–3 are also called vol. 1, nos. 1–3. No. 23/24 is a double issue.

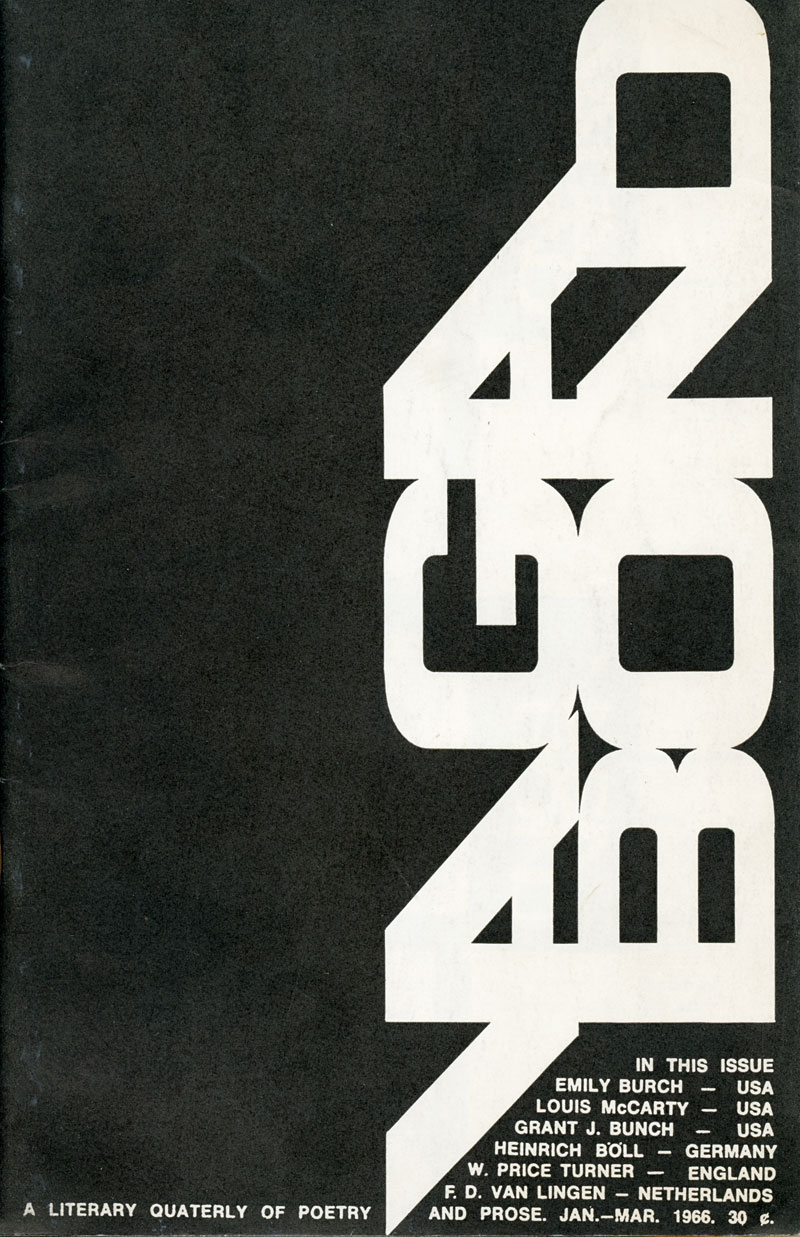

Vagabond, vol. 1, no. 1 (January–March 1966).

Vagabond began in the fall of 1964 over a pitcher of beer at a place called Brownley’s in Washington, D.C. Brownley’s was located on M Street near the George Washington University. It drew a quasi-intellectual crowd from the university and featured cheap draft beer and booths with heavy wooden tables with the initials and slogans of several generations carved into them. It has since been torn down.

Grant Bunch and I were the parties drinking that pitcher of beer, the first of many together over the years, and we were experiencing a hard-to-pin-down dissatisfaction. The dissatisfaction was not new to us, and on this particular day it found a target in The Potomac, then and for all I know still the literary organ of George Washington University. ”What a piece of shit,” Grant said that day, thumbing thru the scant thirty-two pages of pretension and pretty much summing up the magazine. “Why don’t we start our own magazine?”

We spent the rest of that sunny fall afternoon fantasizing over what we could do with our own magazine, and then we ran out of money and the beer stopped coming and we were out on the street again.

****

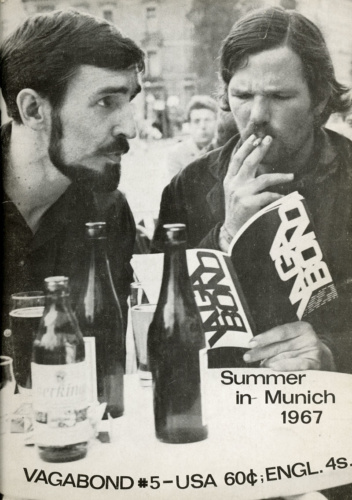

Vagabond 5 (1967).

The scene jumps a year. It is late fall, 1965. I’m in Munich with my wife and son, studying at the university, and Grant is passing thru, on the road. The idea surfaces again, this time by candlelight under the gables of our single fifth-storey room, candlelight because the electricity isn’t hooked up, candlelight and a bottle of good wine and Radio Luxembourg in the background on the portable radio. We talked about the possibility of starting a magazine and the excitement built until names began fluttering around the room like fat gray moths. The Lost Muse, The Munich Quarterly, The Underdog, and why not call it Vagabond, my first wife says, and that’s it. A poem I’d written several years earlier. A rather tightly structured piece of poesy, hardly an indication of what we would soon be publishing, but for curiosity’s sake, here it is:

VAGABOND

Cyclopean, wind-heaving sky up above

As we hie up with vigour

through galloping country.

Cresting a hill and caressing the heavens

Swoop down through the village streets

Rough-hewed and cobbled.

As snarling our cycle

Greets indolent structures

(Age-old Germanic. all somber about us)

Then out again, free again

France Spain who knows

Where the Vagabond wanders.

Tenacious of life.

So, Vagabond it was. I quit the university and went to work washing dishes and my wife became a German postal employee. Grant went off around the world on Norwegian freighters and Maria Spaans came down from the Netherlands to design the Vagabond logo and, along with Peter Halfar, take charge of layout and design. We located the Brothers Westenhuber, a sympathetic printer who did our printing at what must have been cost, and, in April of 1966, the first issue appeared. We published a total of five issues in Munich over the next fifteen months, and then our financial situation became so bad that we were forced to return to the States. We wound up in New Orleans.

****

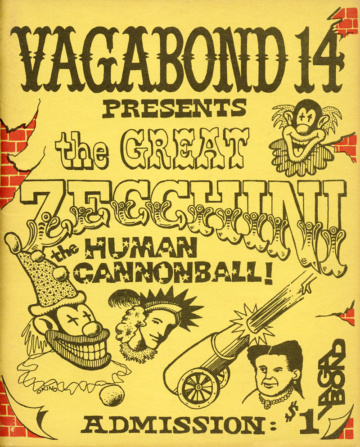

Vagabond 14 (1972). Cover by Craig Okino.

It was in New Orleans that the personality of the magazine began to take shape. It took five or six issues to burn out the preconceptions, that many issues to begin to realize that whether the magazine was quarterly or annual or semiannual had nothing to do with good literature—you could bring the mag out twice in a month and then once in two years and everything would be fine if the stuff between the covers was good; you could bring it out on gloss paper using a letterpress or on a mimeo using recycled paper and it didn’t make any difference; my God, you could print the magazine with rubber stamps and that wouldn’t matter, that would not make it bad and it would not make it good, the method by which you got the word out was incidental, the important thing was to get it out, the important thing was to go after all those vague dissatisfactions, to get at the core of them, to not fall for the soft persuasions and rationalizations, to not cower in the foothills of the mountain of accumulated historical evidence that tells you you are wrong, to keep your eye on it and keep moving toward it until you hit it, you strike that chord that lies deep inside all of us and you say something that is true and always has been true and always will be true and is not and cannot be compromised and rationalized and frittered away, can only be lost from sight—you say it and do it and it is a poem, no matter what the form.

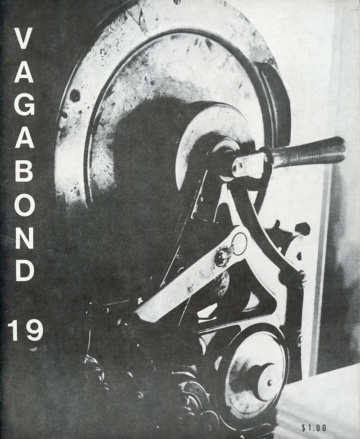

Vagabond 19 (1974). Cover design by Cindy Bennett, photography by George Stillman.

And so an editorial bias began to take shape. Glenn Miller, who became art editor in New Orleans, found a 1917 A. B. Dick open-drum mimeo in a spring-cleaning garbage heap. We tore it down, cleaned and repaired it, and for the next six years all issues of the magazine and all Vagabond books were printed on that mimeo. Since New Orleans we’ve operated out of San Francisco, Redwood City, and now Ellensburg, Washington. Since New Orleans our editorial policies haven’t changed. We don’t cater to fads, panaceas, revolutions, or movements. We don’t aim to make you happy just to let you down. We think that poetry is content, not form, form being incidental, the Cadillac in which the diplomat rides. We think poetry is potent, spiritual, and mysterious. It is not a plaything. It is as scarce and illusive as it has always been. Its only reward is in its discovery, and you discover it thru clear vision, a flash of insight in the vast black mystery of your very brief existence. This society and this species is optional. Other options do exist and still may be taken. Imagination is far more important than knowledge, Albert Einstein once said. What he did not say is that too much knowledge without enough imagination is a dangerous thing. A terminal thing. This anthology and the books and issues of the magazine that came before it and the books and issues of the magazine that will come after it are small black bombs for the playpen of the future. They are time capsule messages that may or may not do some good some day. Here, let Henry Miller wrap it up for me:

THE TIMES ARE ALWAYS BAD …

Anything less than a change of heart is sure catastrophe. Which, if you follow the reasoning, explains why the times are always bad. For, unless there be a change of heart, there can be no act of will. There may be a show of will, with tremendous activity accompanying it (wars, revolutions, etc.), but that will not change the times. Things are apt to grow worse, in fact.

To imagine a way of life that could be patched is to think of the cosmos as a vast plumbing affair. To expect others to do what we are unable to do ourselves is truly to believe in miracles, miracles that no Christ would dream of performing. The whole social-political scheme of existence is crazy—because it is based on vicarious living. A real man has no need of governments, of laws, of moral or ethical codes, to say nothing of battleships, police clubs, high-powered bombers and such things. Of course a real man is hard to find, but that’s the only kind of man worth talking about. It is the great mass of mankind, the mob, the people, who create the permanently bad times. The world is only the mirror of ourselves. If it’s something to make one puke, why then puke, me lads, it’s your own sick mugs you’re looking at!

That’s it. What we have in this anthology was culled from the first twenty-five issues and the first eleven years of the magazine. We hope you enjoy it.

— John Bennett

Editor

Vagabond Press

“Introduction” to The Vagabond Anthology (1966–1977), edited by John Bennett ([Vagabond Press], 1978).

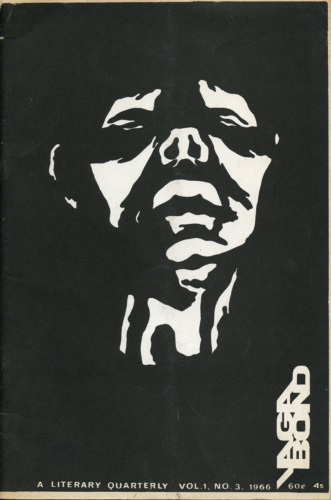

Vagabond, vol. 1, no. 3 (1966).

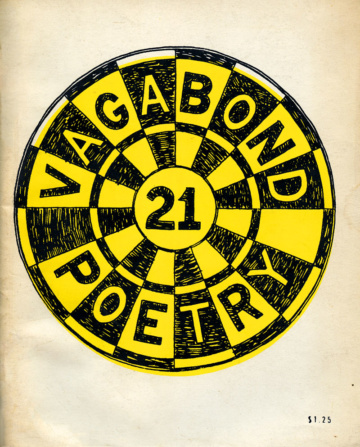

Vagabond 21 (1975). Special Vagabond Poetry issue.

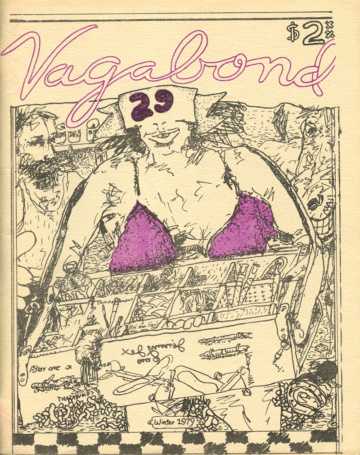

Vagabond 29 (1979). Cover by Jimmy Jet.