# Magazine

Brian Breger, Harry Lewis,

and Chuck Wachtel

New York

Nos. 1–18 + 3 unnumbered issues: April 1978 (precedes # 1), El Clutch Y Los Klinkies by Victor Hernández Cruz, 1981, and “Infinite #,” September 1983 (1978–83).

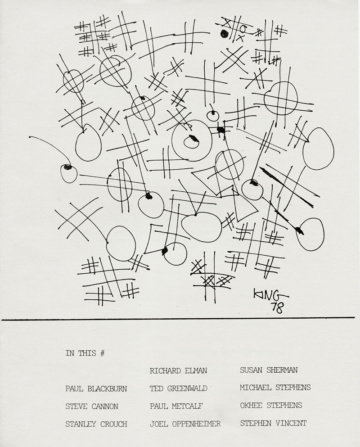

# 1 (May 1978). Cover by Robin Tewes.

I met Brian Breger and Chuck Wachtel on a Friday sometime back in 1973 or ’74. I know it was a Friday afternoon, because I was tending bar at the Tin Palace (three days each weekend starting on Friday). They walked in: Brian, tall and lanky, and Chuck, small and wiry. They introduced themselves as young writers and students/friends of Joel Oppenheimer, whom they studied writing (and life…) with up at City College. Joel had told them to go and find me and “hang out.” We’ve been hanging out (one way or another) since then.

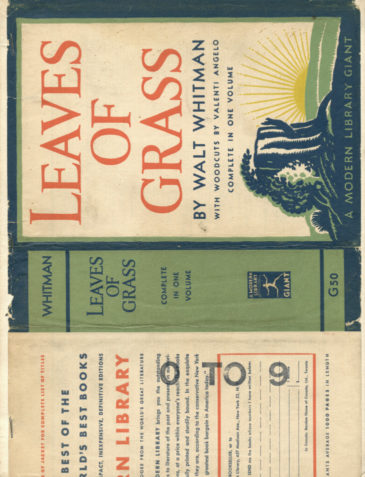

# [unnumbered] (April 1978). Cover by Basil King.

After a few years we started doing chapbooks and finally got a New York State Arts grant to keep publishing. By that time we had enough work for about another year, but we had each gone off in other directions and we just decided it was time to end it. We decided to do one last big # and then retire the project. But it has had a life of its own and still comes up in many different accounts of that time back then, back there—it has become HISTORY.

ONE LAST THING: the name of the mag is #, not number. The name was given to us by Ted Greenwald who simply said, one day, when we were all trying to come up with a name, “Here, this is it: #. Not the word, the sign—get it?” And we did.

Some More on #

When I look back at all that we did (History and Memory now) it seems hard to imagine that we did that much and it seemed—just what we did and just part of our lives …

I look at the list of contributors and each brings back a moment. That’s the great thing about doing a magazine that is so personal and a regular part of your routine.

We published almost everyone we were connected to as writers: Basil King (both as artist and writer: who he is), Martha King, Susan Sherman, Michael Stephens, Steve Vincent, Paul Metcalf, Toby Olson, Rochelle Owens, George Economou, Robert Kelly, Michael Lally, Richard Ellman, Ted Greenwald, Joel Oppenheimer, Hubert Selby, Joe Johnson, Hettie Jones, Maureen Owen, Oliver Lake (almost nobody knew he was a great poet as well as a world-class composer/musician—I had the great pleasure of performing with him and he was surprised when we wanted to publish him!), Allan Kaplan, Jack Marshall; and then we decided to do some chapbooks and they were really special and still hold up—particularly Paul Blackburn’s By Ear (the third time I was able to publish a book by the central figure in my own coming-of-age as a writer and translator). There were also translations: my Mayakovsky, George Economou’s Cavafy, Phileodemos, Armand Schwerner’s Max Jacob, and others.

AND Robin Tewes’s art and art direction and a wide range of artists who became part of the whole experience.

We decided to end things and were about to publish the last full collection of short stories by Hubert Selby Jr. when a major publisher decided to bring it out. The pleasure was in knowing that it was Chuck Wachtel and I that had edited and gotten the whole thing rolling; and finally that was what it was all about: getting the whole thing, that we were part of, rolling.

— Harry Lewis, New York, March 2017

# [unnumbered] (December 1978). By Ear by Paul Blackburn. Cover by Robin Tewes. This is a special unnumbered issue of # magazine.

Infinite # (September 1983). Cover by Robin Tewes. This is a special unnumbered issue of # magazine.