Momentum and Momentum Press

Bill Mohr

Los Angeles

Nos. 1–8 (1974–78).

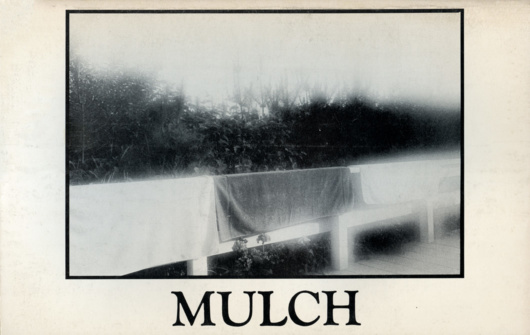

Momentum 2 (Summer 1974).

When I moved to Los Angeles in 1968, I didn’t expect to meet so many poets living outside of the realm of academic affiliations. The intermittent reading series at Papa Bach Bookstore had prompted me in the fall of 1971 to undertake being the first poetry editor of the store’s nascent magazine, Bachy, and I had gone out in search of poets who were interested in being more than local, especially given that we were living in a city globally renowned for its industrial production of culture. While many clusters of poets in L.A. were too small at the start of the 1970s to be called scenes, one of my first realizations of their potential for creating an alternative narrative to the corporate consciousness of the East Coast publishing world came about through my reading of Invisible City, which was edited by Paul Vangelisti and John McBride. Both of them had also started Red Hill Press as a book publishing project.

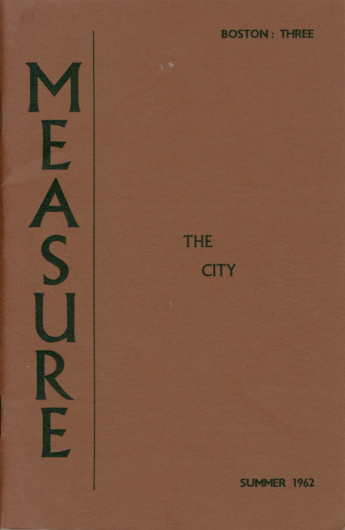

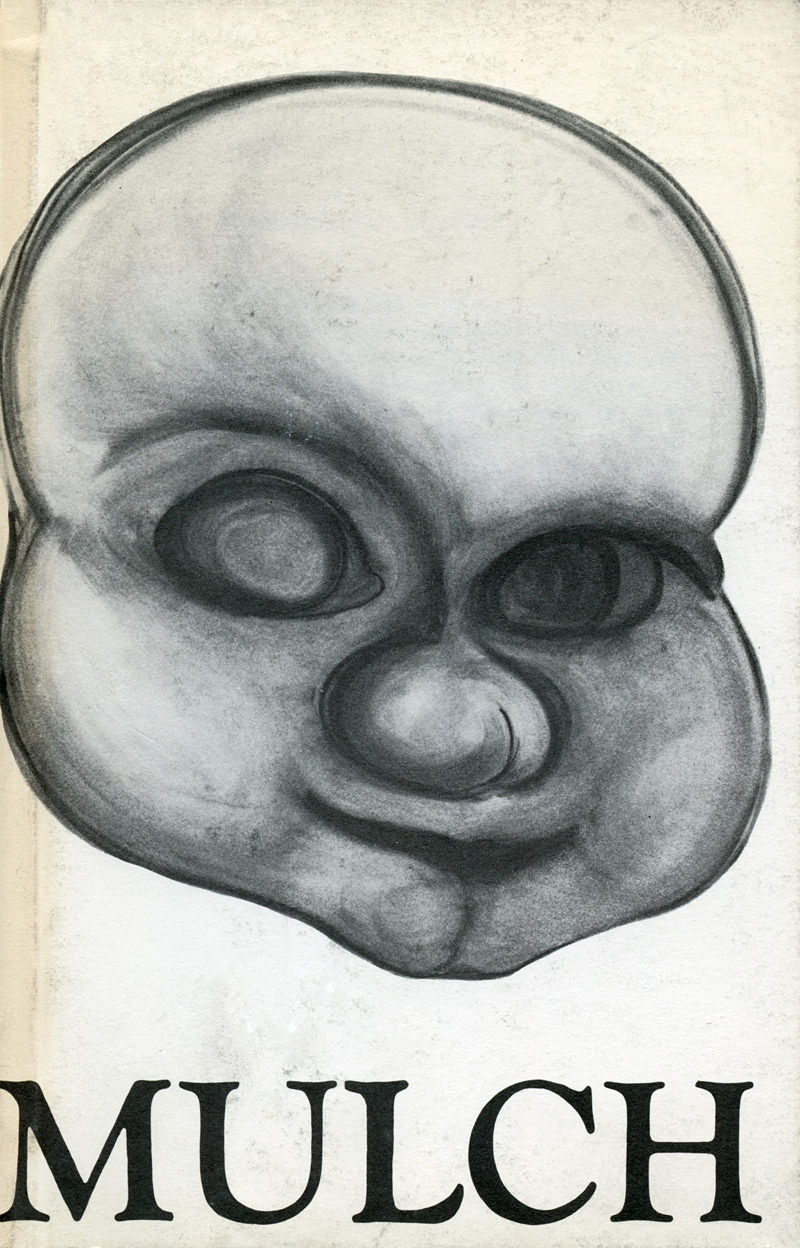

Momentum 5 (Summer 1975).

After meeting poets such as James Krusoe, Harry Northup, Kate Braverman, and Lee Hickman at Beyond Baroque’s Wednesday night poetry workshop, I started my own magazine as a way of contributing to this conversation, and started receiving poems from other young poets such as Garrett Hongo, who was then living in the San Gabriel Valley, and Wanda Coleman, who had grown up in Watts. The amount of poetry available to be published far exceeded what any one magazine could possibly hope to encompass, and I found it impossible to resist the temptation to publish books, too. Other institutions, such as the Woman’s Building, also served as sites of inspiration for manuscripts, such as Holly Prado’s Feasts, which I published along with a score of other titles between 1975 and 1985.

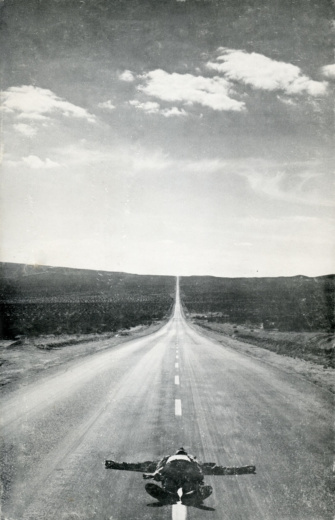

Momentum 7/8 (Fall 1976/Spring 1977). Cover photograph by Michael Mundy.

My poetry magazine, Momentum (1974–78), primarily focused on poets living in Los Angeles County, but I also featured poets such as Alicia Ostriker (New Jersey), Len Roberts (Pennsylvania), Jim Grabill (Ohio; Oregon), as well as Minnesota poets Patricia Hampl and Jim Moore; I went on to publish books by Ostriker, Roberts, Grabill, and Moore. The first of two anthologies I edited in this period, The Streets Inside, only partially caught the flourishing quality of the L.A. scene by the late 1970s. By the mid-1980s, other editors and publishers such as Dennis Cooper (Little Caesar) and Lee Hickman (Bachy and then Temblor) had firmly established Los Angeles as a setting that refused to settle for predictable literature. I edited a much more comprehensive anthology (Poetry Loves Poetry) in 1985, after which I only published a few chapbook projects and limited edition books.

It should be noted that not all those associated with the academy remained isolated from this effusive embodiment of imaginative writing in Los Angeles during this period. Clayton Eshleman’s Sulphur also challenged the poets living in Southern California to read with unwavering commitment to the Republic of Literature. Finally, it cannot be said often enough that Beyond Baroque’s willingness to serve as a production center for many of these editors and publishers was the single most important factor in all of this coming to pass, and that the independent bookstores such as Chatterton’s, Sisterhood, Either/Or, and George Sand, as well as Papa Bach, remain blissful legends in my memories.

— Bill Mohr, Long Beach, California, March 5, 2017

Momentum Press books (complete)

Barnes, Dick. A Lake on the Earth. 1982.

Braverman, Kate. Milk Run. 1977.

Castro-Leon, Sophia. Before the Hawk Gets Off My Head. 1977.

Ellman, Dennis. The Hills of Your Birth. 1976.

Ford, Michael C. The World Is a Suburb of Los Angeles. 1981.

Grabill, James. One River. 1986.

Hickman, Leland. Great Slave Lake Suite. 1980.

Hansen, Joseph. One Foot in the Boat. 1977.

Hansen, Joseph. The Dog and Other Stories. 1979.

Krusoe, James. Small Pianos. 1978.

Krusoe, James. Notes on Suicide. 1976.

Kincaid, Michael. Inclemency’s Tribe. 1990. Drawings by Robert Johnson.

Levitt, Peter. Two Bodies Dark/Velvet. 1975.

Metzger, Deena. Dark Milk. 1978.

Mohr, Bill. Penetralia. 1984.

Mohr, Bill, ed. “Poetry Loves Poetry”: An Anthology of Los Angeles Poets. 1985. Photographs by Sheree Levin.

Mohr, Bill, ed. The Streets Inside: Ten Los Angeles Poets. 1978.

Moore, James. What the Bird Sees. 1978.

Northup, Harry E. Enough the Great Running Chapel. 1982.

Northup, Harry E. Eros Ash. 1982.

Ostriker, Alicia. The Mother/Child Papers. 1980.

Prado, Holly. Feasts. 1976.

Roberts, Len. Cohoes Theater. 1980.

Roddan, Brooks. The Second Dream. 1986.

Thomas, Jack. Waking the Waters. 1978.

Thomas, John, and Philomene Long. The Book of Sleep. 1991.

Warden, Marine Robert. Beyond the Straits. 1980.

Resource

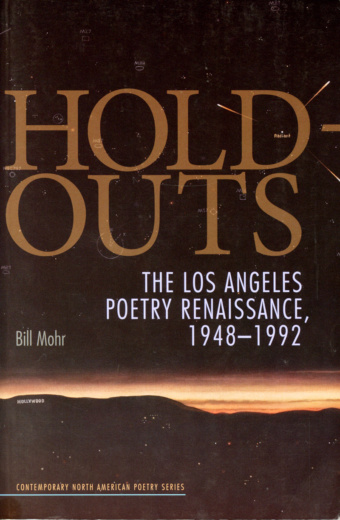

Bill Mohr’s book on the poets, small presses, and little magazines of the Invisible City is dense with ideas and information. Highly recommended.

Bill Mohr, Hold-Outs: The Los Angeles Poetry Renaissance, 1948–1992. University of Iowa Press, 2011.

![Maps 1 [1966]. Cover: Herbert Bayer, “Graphic Fragment #2.”](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/maps-1-r-599x530.jpg)

![Maps 3 [1970]: Poems for John Coltrane. Cover by Roger Shimomura.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/MAPS-no-3-1970-r-455x530.jpg)