Hot Water Review began during a wave of poetry activity in 1970s Philadelphia, when the American Poetry Review (APR), Painted Bride Quarterly (PBQ), the now-defunct Philadelphia YMHA Poetry Center, and numerous reading series and workshops were established. The city’s mass media began to acknowledge the poetry explosion; Philadelphia Magazine published a story about the local poetry scene, poets appeared on TV and radio, and the alternative weeklies regularly featured poetry.

Joel Colten and I created Hot Water to meet a need. APR primarily published national and Philadelphia poets with academic affiliations. PBQ published a wide range of poets and aesthetics and served as a sort of anthology of what was happening in various literary communities. But there was no venue for what interested us.

We wanted to explore visuals as well as poetry. Our interests included Pop and its attendant irony, the New York School and all its offshoots, and Conceptualism. We created Hot Water to showcase this sort of work. Through our involvement with the magazine we came in contact with like-minded people throughout the country. It was a very exciting time.

The first issue of our magazine, which appeared in 1976, had an anthology approach similar to PBQ’s. We published a significant cross section of fellow Philadelphia poets with various aesthetics, along with a smattering of people from the UK, New York, and Boston. After that we began to focus on our particular interests.

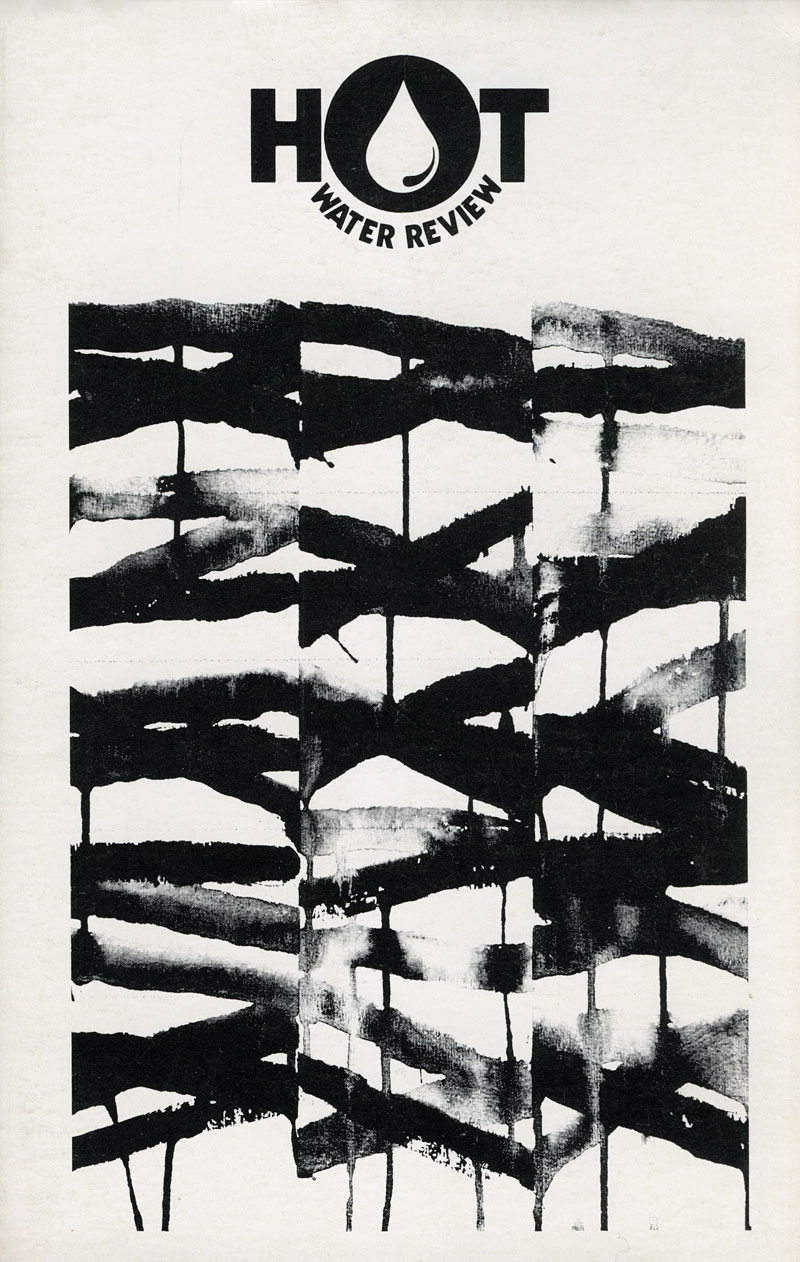

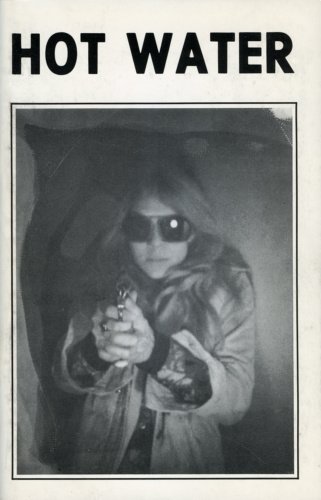

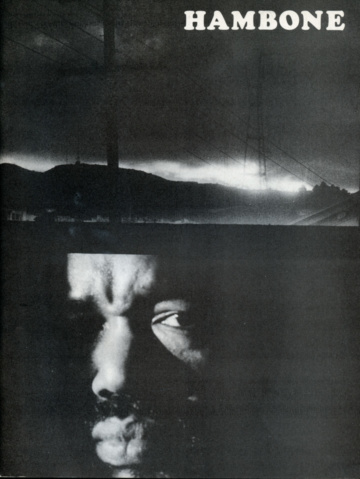

Hot Water Review 2 (1977). Front cover photograph by Joel Colten.

Issue 2 (1977) presented lots of visuals, including “snapshots” of poets, artists, and musicians; art, photography, and conceptual work by Annson Kenney, Anne Sue Hirshorn, Anthony Errichetti, Sue Horvitz, Stephen Spera, and others; and poetry/art collaborations by Joel Colten and Randal Rupert. The writing in this issue included work by Philadelphians Diane Devennie, Susan Daily, Jet Wimp, Maralyn Lois Polak, Jane Vacante, Otis Brown, Leonard Kress, Joel Colten, and me; Californians Ian Krieger and Pat Nolan; and New Yorkers Tim Dlugos, Andrei Codrescu, David Lehman, Michael Malinowitz, Gerard Malanga, and Dorothy Friedman. Our overall goal: to create a scrapbook representing a community of creative people who shared similar instincts.

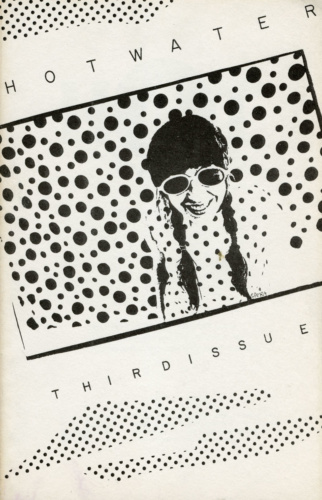

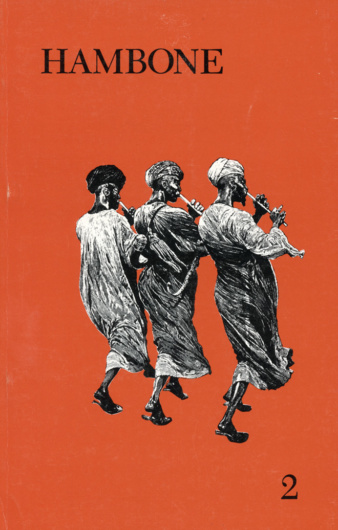

Issue 3 (1980) was the peak of our Pop-inspired “ragged scrapbook” approach. The cover, which was designed by Stephen Spera, featured polka dots. There was another photo album of Hot Water contributors, friends, and family; a poem/memoir of a radicals’ party during the Vietnam War by playwright/poet Dennis Moritz; and work by Dennis Cooper, Opal L. Nations, Harrison Fisher, Jack Anderson, Michael Lally, Michael Andre, and Hot Water regulars Codrescu, Colten, Rupert, Spera, Bushyeager, Devennie, and Daily.

Hot Water Review 3 (1980). “The Polka Dot Issue.” Cover photograph and design by Stephen Spera.

Right before this issue was published, coeditor Joel Colten went on a cross-country trip and stopped to photograph the Mt. St. Helens volcano, which had recently become active. Unfortunately, he was one of the casualties of the May 18, 1980, eruption.

After considerable soul-searching, I decided to continue Hot Water but change its visual identity. The magazine’s previous iteration reflected Colten’s and my partnership and our youthful enthusiasms. It was difficult, but I recognized that times had changed and I needed to honor the past while moving forward. As the sole editor, I chose the writing that appeared in the magazine. However, I added seasoned NYC gallerist Richard Oosterom as art editor. For the first time, Hot Water engaged the services of a professional designer who gave the magazine a total, elegant makeover that included a sans serif typeface and a square format that worked better with visual art.

Hot Water #4 was published in 1981. It had a very simple cover: pink textured paper with red title lettering. The issue began with an in memoriam two-page frontispiece featuring a brief poem by Joel Colten accompanied by a Randal Rupert drawing of Colten among the stars with his dog, Phineas. In addition to more Colten/Rupert collaborations, there was a portfolio of work by New York artists Aileen Bassis, Patricia Caire, and Rupert. The writers included Harrison Fisher, Ron Padgett, Richard Kostelanetz, and Hot Water stalwarts Devennie, Colten, Krieger, and Codrescu.

Although I continued my involvement with poetry during the years immediately following Hot Water #4, I primarily focused on setting the stage for a move to New York by building a portfolio of freelance journalism and arts criticism. Although monetary resources were dwindling, I published a fifth issue of the magazine in 1983 that focused almost exclusively on writing by, in addition to some of the magazine’s regulars, Dennis Barone, Arthur Sabatini, and fiction writer Susan Schwartz.

In 1984 I moved to New York and took a job as a nonprofit editor whose tasks included responding to fan letters written to the comedian Jerry Lewis and writing scripts for his annual telethon (a curious job to be sure!). I continued to write freelance arts reviews, became intensely involved with the downtown poetry scene revolving around the Poetry Project, and took workshops with Alice Notley, Bernadette Mayer, Maureen Owen, and Lewis Warsh. This vibrant literary community revitalized me.

I published one last issue of the magazine in 1988. It was a single-artist issue: Shadow Blue, a chapbook by poet Phyllis Wat whose work I had admired for some time.

* * * *

I recently attended a small-press book fair on the NYU campus. There were many presses in attendance and excitement was in the air. The mostly young editors and publishers were proudly displaying their publications, which included a substantial number of poetry collections. The event took me back to the small-press book fairs of the seventies and the intense “alternative” energy that all of us had. I was reminded that new poets are constantly being brought into the world via the dedication of small-press editors and publications. I felt proud to be a part of this important tradition.

— Peter Bushyeager, New York, May 2017