Dark Ages Clasp the Daisy Root

Benjamin Friedlander and Andrew Schelling

Berkeley, and Boulder, Colorado

Nos. 1–8/9 (1989–93).

Dark Ages Clasp the Daisy Root 6 (2nd series, no. 1) (June 1991).

The title comes from Finnegans Wake though we drew it from Edith Sitwell. Up all night knowing we wanted a “flower” name we consulted the I Ching to find something from her anthology of flower phrases. We had signed off on the final issue of Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K” telling its readers that we would probably found another journal, but needed to “rethink the labor intensive, almost paleolithic technology” we’d used up to 1989.

The flower title was a respectful homage to compost. We had written to friends saying, “out of the mulching of Jimmy & Lucy’s etc., etc.,” and received a dismissive note from a Marxist language poet telling us how that type of agrarian metaphor was obsolete, etc., etc., in the post-industrial landscape. Joyce’s phrase seemed apt, growing sunflower-sutra-like out of a seedbed from Edith Sitwell, and meant to charm the most dogmatic Marxist.

Dark Ages Clasp the Daisy Root 7 (2nd series, no. 2) (April 1992).

At first we moved from paleolithic technology to mimeo mag of the sixties production: typed 8½ x 11-inch pages. Writers sent their ready-to-photocopy poems. We only had to add page numbers, run it all through a photocopy machine, and insert staples. Personal computers emerged about issue 6 (June 1991). Now we could compile a single document, print it out, and run it through Xerox. We also readjusted the focus, away from language poetry of the Bay Area and toward a more international view and deeper sense of time. We included translations from the start. In 1989 Schelling moved to Colorado, so most issues were coedited, not in an apartment together and typed up over all-night coffee, but 1,200 miles apart. Always we ran a poem on the rear cover. The first issues had end-poems by Larry Eigner, Alice Notley, an anonymous Middle English lyric translated by Norma Cole, Hebrew translation by Peter Cole. Inside were Hannah Weiner, Susan Howe, Rachel Tzvia Back, Nathaniel Mackey, Joanne Kyger, Lorca, Pasolini, fifth-century BCE Sanskrit, Red Grooms and Anne Waldman, Paul Celan, Charles Baudelaire, and Ingebor Bachman. Comparing the contributors with Jimmy & Lucy’s shows instantly that the core of the magazine remained a few East Bay poets we knew closely, but the interests had shifted to myth, history, languages, peyote ceremonies, and the archaic.

Dark Ages Clasp the Daisy Root 8/9 (2nd series, nos. 3/4) (June 1993). Cover art by Anne Waldman and Andrew Schelling.

The final issue 8/9 held only translations. We drew some from faculty and students at Naropa, where I was now teaching. Anselm Hollo entered the mix with “Some Greeks,” back at the salty beginnings of Occidental poetry.

— Andrew Schelling, Boulder, Colorado, January 2017

Resource

Tables of content and scans of the complete run of Dark Ages Clasp the Daisy Root are available on Benjamin Friedlander’s website.

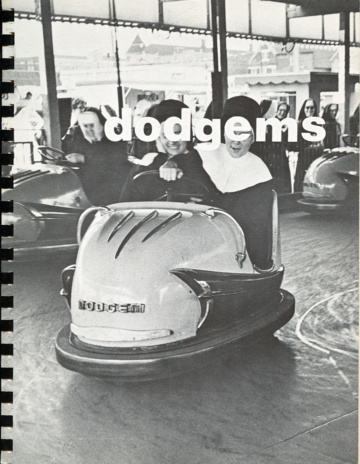

![Dodgems [2], 1979.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/eileen-myles-dodgems-2-1977-r-412x530.jpg)

![Detroit Artists Workshop Benefit: Seven Poets, Santa Fe-Albuquerque. Captain Mimeo and the Pepsi Shooter Press Book no. 1. [Duende Press], March 11, 1967.](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/detroit-family-r-407x530.jpg)

![Charles Olson, Mayan Letters (1953 [i.e., 1954].](https://fromasecretlocation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/charles-olson-mayan-letters-divers-press-r-409x530.jpg)