The Alternative Press

Ann and Ken Mikolowski

Detroit; Grindstone City, Michigan; and later Ann Arbor, Michigan

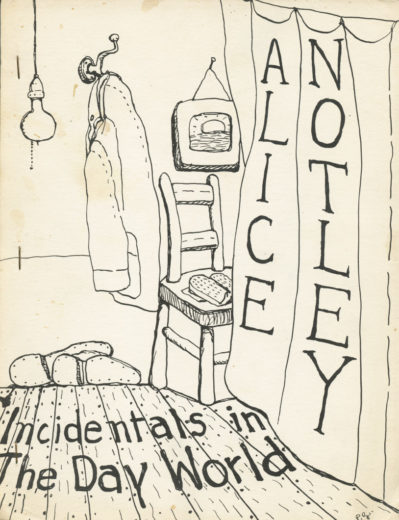

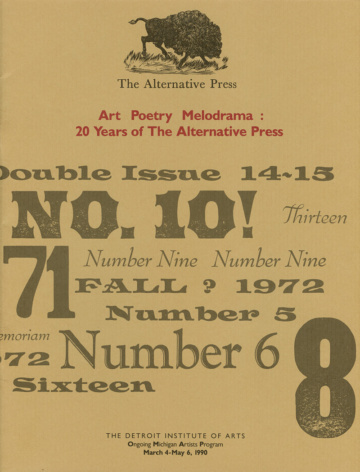

The Alternative Press Subscription Mailings [Art, Poetry, Melodrama] [1]–[20] (Fall 1972–2006). No. 14/15 is a double issue.

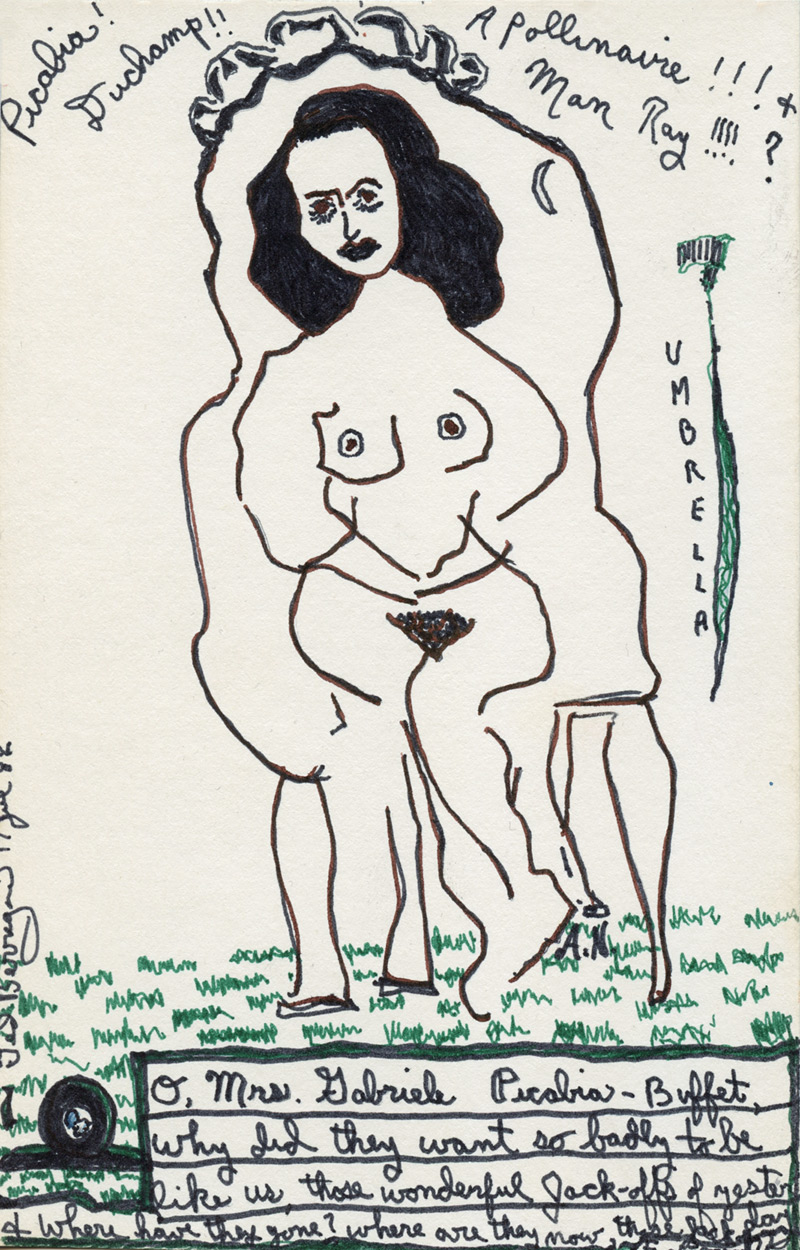

Ted Berrigan, [Umbrella] hand-drawn postcard from the Alternative Press Subscription Mailing 12 (1983). One of 500 unique postcards that provided the basis for Berrigan’s A Certain Slant of Sunlight.

The experimental, innovative, and unpretentious links forged by the Alternative Press between poets and painters recall other legendary collaborations: the poets and painters of the Dada and Surrealist movements in the early part of this century, and, closer to our own time, poet Frank O’Hara and his connection with the New York School painters. The Mikolowskis have sought out contributions from the major figures in the country in contemporary poetry, as well as some of the finest artists. The layering of work by Detroit artists and by artists around the country lends the Press its luster as an important showcase for Michigan artists while disdaining any regional label. Its modest production and low-key approach masks a truly revolutionary spirit.

— Mary Ann Wilkinson, Curator of Modern Art, Detroit Institute of Arts

The Alternative Press began its thirty-year run in a Detroit inner city basement in 1969. Ann Mikolowski, an artist, and myself, a poet, were the recent purchasers of a 1904 Chandler & Price hand-set letterpress. We had never printed before. For us it was the cheapest, but not easiest, way to publish the work of our friends, the poets and artists of Detroit. We provided the labor and all that needed to be bought was paper and ink. But the 1,500-pound press was an intimidating presence and demanded we quickly get up to speed.

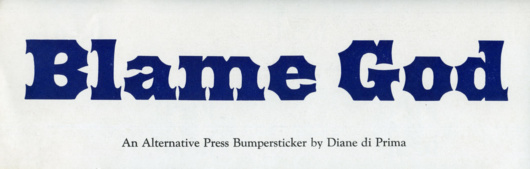

After more than a bit of trial and plenty of error we established our functional format of broadsides, postcards, bookmarks, and bumper stickers.

Diane di Prima, “Blame God” bumper sticker from the Alternative Press Subscription Mailing 19 (1997).

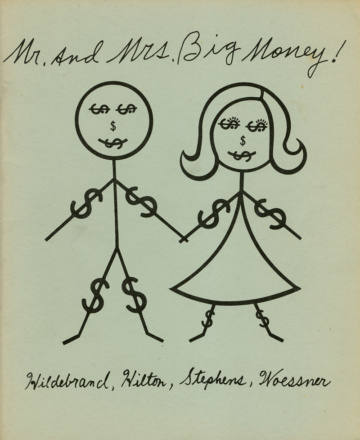

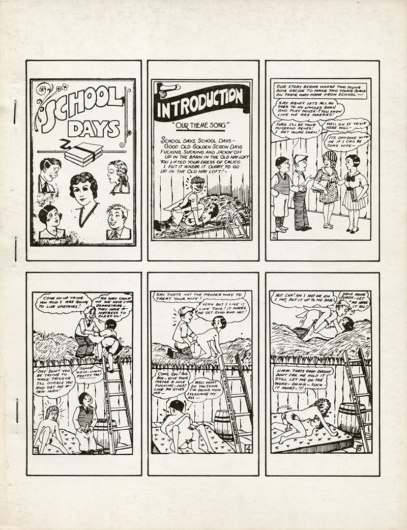

Until, one day, we upped the ante. We found an easy answer to our printing labors: we turned artists and poets loose with 500 blank postcards each, to do with as they pleased. Each card was handmade and unique, no two alike: poems, paintings, collages, photographs, even metal works and ceramics. Everyone brought whatever they had and gave everything they had.

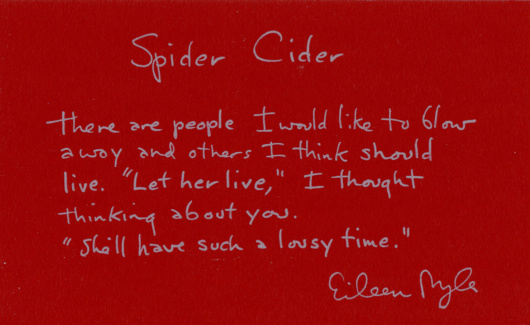

Eileen Myles, “Spider Cider,” letterpress postcard sent out as part of the Alternative Press’s Poetry Postcards, Series 3 [1986].

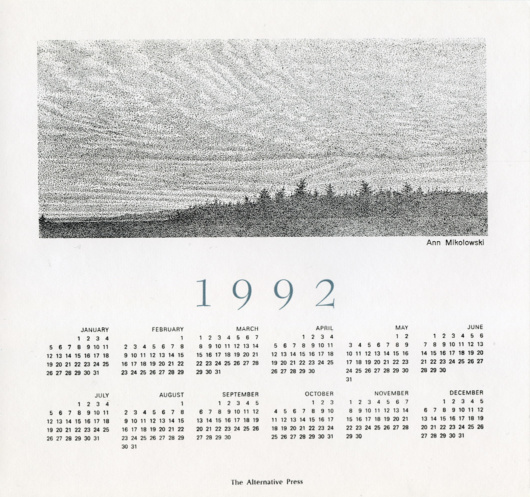

Ann Mikolowski, 1992 [Calendar]. Included in the Alternative Press Subscription Mailing no. 17 (1992).

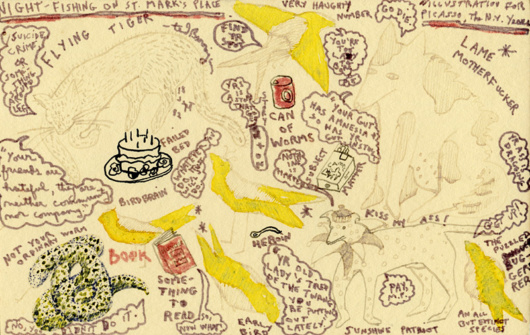

Ted Berrigan [Night-Fishing on St. Mark’s Place]. Hand-drawn postcard from the Alternative Press Subscription Mailing 12 (1983). One of 500 unique postcards that provided the basis for Berrigan’s A Certain Slant of Sunlight.

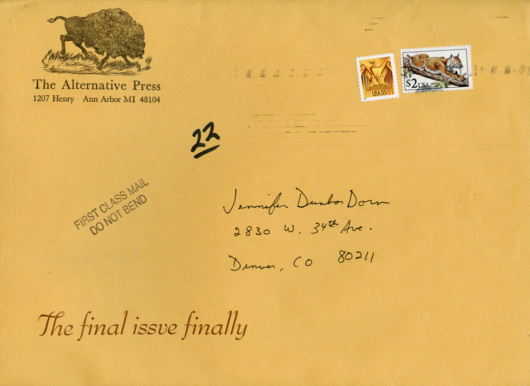

Envelope for the Alternative Press Subscription Mailing [20] “Final Issue, Finally” (2006). Mailed to Jennifer Dunbar Dorn.

— Ken Mikolowski, Ann Arbor, Michigan, March 2017

Resource

Kevin Eckstrom, ed., Art Poetry Melodrama: 20 Years of The Alternative Press. Detroit Institute of Arts, 1990.