Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion

Franklin Rosemont

Chicago

Nos. 1–4 (Autumn 1970–1989).

Editorial board for nos. 3 & 4 included Paul Garon, Joseph Jablonski, Philip Lamantia, Penelope Rosement, and Jean-Jacques Jack Dauben (3 only).

Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 1 (Autumn 1970).

We’re at the foreplay of history.

— Philip Lamantia

Surrealism began, point blank, with life-and-death questions that everyone else ignored or pretended to ignore: questions of everyday life, suicide, madness, nature, poetry, love, language, and absolute revolt. The most audacious dreams of centuries suddenly were dreamed anew and brought to fruition in this new and unexpected “communism of genius” that plunged its roots deep in the manifold forms of outlawed subjectivity. Here was a dialectical leap of world-historical implications, transforming once and for all the conditions of thought, art, poetry, and life itself.

Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 2 (Summer 1973).

And today? To the extent that the tentative answers to surrealism’s questions have been reduced to any of the numerous and all-too-usual evasions—for example: literature, art; or worse: literary criticism, art criticism; or worst of all: a political career—the superficial observer could conclude, as so many have concluded, that surrealism has failed. But can the viability of surrealist intervention, and surrealist solutions, today and here or anywhere, really be proved or disproved by such obviously backhanded book-juggling in the moneymaking ideological sideshows of the dominant culture? All these “surrealist” dictionaries, encyclopedias, doctoral dissertations, TV documentaries, and the whole insidious complex of hypernicious academicynicism and museumification are ridiculous, no doubt about it, but can such sorry displays of commercial confusionism truly be said to have silenced surrealism for all time, so that its own authentic voice can never again be heard?

Most assuredly, if surrealism continues to develop it will be because surrealists continue to develop it. And even if every one of those who call themselves surrealists today threw in the towel, the fight would hardly be over. Surrealism’s questions, in any case, remain defiantly and even horribly open—festering wounds all over the bloated body of christian-capitalist hypocrisy—and quite unphased by the would-be curative incantations of those whose job it is to reassure society’s self-appointed managers that surrealism, like working-class emancipation, is safely obsolete.

Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 3 (Spring 1976).

Even were we to join the inane conformists’ chorus that sings surrealism’s death, it would make little difference, for those who resolve to pursue these questions must sooner or later discover for themselves that inevitably it lives again, albeit perhaps in forms not immediately apprehensible to the pontifically glib horn-tooters of total counterrevolution. As my footsteps carry me along the redbrick backstreets radiant with fallen oak leaves in the morning mist—a raven on the highwire glances down as I glance up: What can this meeting of eyes portend?—it is none other than the author of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell who speaks to me, in a voice clearer than any other, and with a tone of urgency that admits of no mistake:

Without contraries is no progression … Energy is Eternal Delight … Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained … The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom … He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence … All wholesome food is caught without a net or a trap … Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion … What is now proved was once only imagin’d …

To invoke Blake here reminds us that dialectics is not something to which Hegel was awarded an exclusive patent, but rather an insight, a gift of overflowing life, born and reborn ceaselessly in the fires of revolutionary thought and action. And so it is with the cause of poetry, love, and freedom—that is, with surrealism, in a word. In the exceptional and decisive moments and situations of daily life—breaking one’s fetters, falling in love, risking all—surrealism incessantly emerges anew, and ready for anything.

We are living, precariously enough, in a strange place called the United States, a nation founded on genocide, and whose government, the most murderous in history, is the deadliest enemy of human freedom in the world today. Eighteen years after the appearance of the first Arsenal, we surrealists are more than ever communists, anarchists, atheists, irreconcilable revolutionists, implacable enemies of things as they are, unrepentant seekers of a truly free society.

Surrealism continues to advance today, and to make a difference, because it refuses to compromise with unfreedom, because it holds true to its own irreducibly wild and untameable means, outside all repressive frameworks. Anti-statist, anti-sexist, anti-racist, anti-religious, anti-anthropocentric, anti-academic, allergic to Western civilization and its values and institutions, surrealism passes with flying colors what John Muir, one of the greatest of American presurrealists, called the test of the wilderness.

“And how do we reach this truly free society?”

Start by dreaming.

Those who don’t know how to cross their bridges before they come to them will never get anywhere.

— Franklin Rosemont, “Now’s the Time.” Editorial in Arsenal 4 (1989)

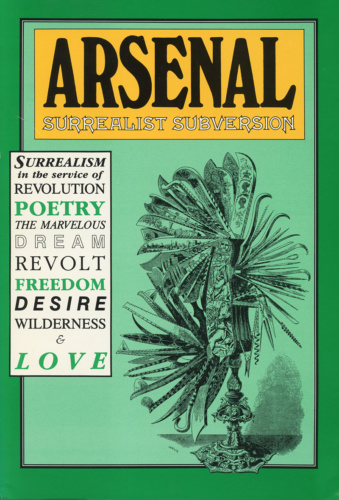

Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 4 (1989).