First Intensity: A Magazine of New Writing

Lee Chapman

Staten Island, New York

Vol. 1, nos. 1–22 (Summer 1993–Fall 2007).

Issues after vol. 1, no. 2 lack volume designation.

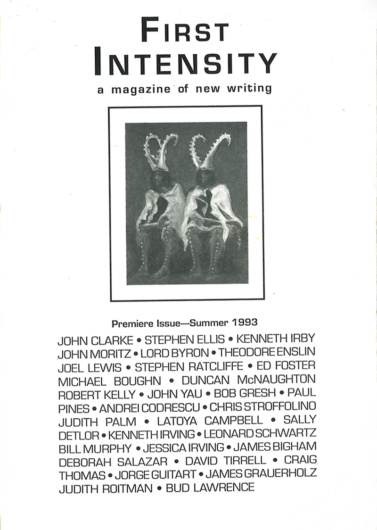

First Intensity: A Magazine of New Writing, vol. 1, no. 1 (Summer 1993).

The artist Lee Chapman started the literary magazine First Intensity in 1993 when she was living in Staten Island, New York. By issue #6 in 1997 she was back in her old not-exactly-hometown of Lawrence, Kansas, where First Intensity continued to be produced until issue #22, which turned out to be the last one, in 2007. Twenty-two issues in fifteen years. Not bad. And these issues were pretty substantial—in the beginning they were about 120 pages or so, by #16 in 2001 the length grew to over 270 pages and stayed there.

Why did she do it? Lee had wanted to run a literary magazine for a long time. The way she tells it, she had a hard time finding what she liked to read. So when a small inheritance appeared she decided to collect what she liked in one place and make it available for others to read. Hence, First Intensity.

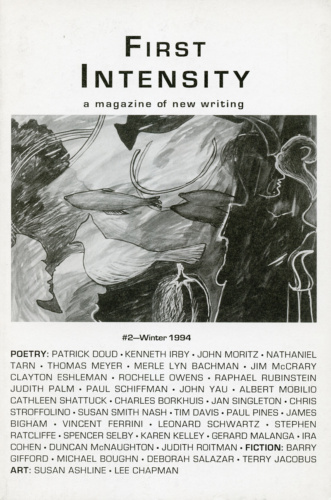

First Intensity: A Magazine of New Writing, vol. 1, no. 2 (Winter 1994). Cover by Susan Ashline.

How did she do it? Lee wasn’t part of any literary scene—she’s an artist, not a writer—but she knew a few poets from her years at the University of Kansas—Ken Irby, John Moritz, Jim McCrary. One of her friends (Jim McCrary) worked for William S. Burroughs and had access to an extensive list of writers’ addresses. So Lee made up some postcards that said First Intensity Magazine and sent them out to some writers she admired, none of whom knew her, soliciting their work. They sent work in. She sent more postcards to more people who also didn’t know her, citing the work she’d already accepted. And more work came in, until she had about 120 pages’ worth. Lee published good work, writers recognized this, so she didn’t have to send out any more postcards, the work just came to her, mostly unbidden, sometimes solicited when she knew someone was writing something she really liked. It is not the usual story of how literary magazines get started—by one person entirely on her own who wasn’t a writer and didn’t know many writers—but that is how it happened.

First Intensity was substantial from the beginning. Issue #1 included Andrei Codrescu, Stephen Ellis, Ted Enslin, Kenneth Irby, Robert Kelly, Duncan McNaughton, John Moritz, Stephen Ratcliffe, Chris Stroffolino, and John Yau, among many others (including, full disclosure, me). There was also art: etchings by Bill Murray—no, not that Bill Murray—and cover art by Lee’s daughter, Jessica Irving, which is not exactly nepotism because Jessica is a terrific artist. Good art remained a staple of First Intensity, one or two or more artists an issue.

Over time a kind of stable of writers developed, with generous helpings of work from others—Ken Irby appeared in fourteen issues, Barry Gifford and Ted Enslin in thirteen, Duncan McNaughton and John Moritz in twelve, John Olson and me in eleven, Nathaniel Tarn and Robert Kelly in ten. Six authors appear in seven issues, two in six, six in five, thirteen in four, thirty in three, sixty-eight in two, and 243 appear exactly once—380 authors in all. (I am including three translators in this count, along with their translatees, and—Lee is nothing if not quirky—Lord Byron, one of whose letters appears in #1.)

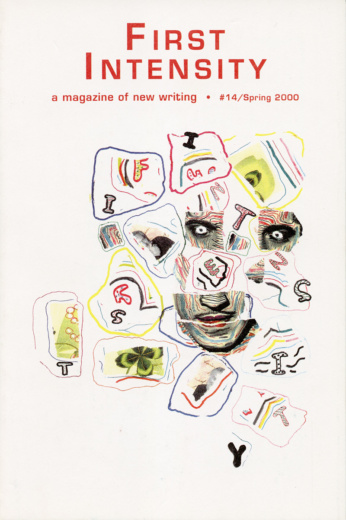

First Intensity: A Magazine of New Writing 14 (Spring 2000). Cover collage by Kenward Elmslie.

Reviews and occasional essays started appearing with #14. At first, most of the reviewers and reviewed were First Intensity authors (in issue #16 Dale Smith had a poem, a review, and was reviewed, an untypical trifecta) but the group of reviewers and reviewed soon broadened beyond the usual First Intensity suspects. The reviews were a substantial part of First Intensity—twenty books were reviewed in #17, eighteen in #18.

A few years after starting the magazine Lee established First Intensity Press, which published books by Lisa Bourbeau, Patrick Doud, Theodore Enslin, Barry Gifford, Kenneth Irby, John Levy, Duncan McNaughton, John Moritz, John Olson, Kristin Prevallet, Janet Rodney, James Thomas Stevens, and, full disclosure, me. (If I left someone out, apologies.)

Lee valued her independence perhaps more than is useful. She did not want to hook up with any institution. She did not want to answer to anybody. She refused to send in grant applications, fearing a grant would make her beholden in some way, force her to conform to someone else’s vision. Her friends kept telling her no no no that’s not how it works for God’s sake I’ll write the goddam grant for you, but she just wouldn’t do it. Her small inheritance was running out, maybe was already gone, and she was doing the magazine and press (she did everything—editorial, proofreading, typesetting, formatting, addressing, mailing—except the actual printing) on financial fumes until an angel stepped in somewhere around issue 17 or so. She refuses to this day to identify the angel. The angel didn’t last forever, Lee was running out of both money and energy, so the magazine stopped. The press went on a little longer, but then it stopped too.

First Intensity: A Magazine of New Writing 22 (Fall 2007). Cover painting by Claire Doveton.

Lee doesn’t regard the work she published as presenting a coherent aesthetic, but I think it does, at least the poetry: a kind of romantic postmodernism. There is a richness of tone and sound, a sense of the author—that is the romantic part. But also there are fragmentation, incoherence, juxtaposition, a sense of the author dissolving—that is the postmodern part. Lee doesn’t think of it that way. She thinks of the work she published in light of Ezra Pound’s dictum: “The work of art which is most ‘worth while’ is the work which would need a hundred works of any other kind of art to explain it … Such works are what we call works of the ‘first intensity’.” That’s Lee’s poetics, and it provided the name of the magazine and press.

Lee was not good at the interwebs. There are a few scattered reviews of the magazine online, but no samples/examples of work traceable to the magazine. And the press disappeared as a coherent entity—no list of books published. Maybe this is the way of the world, but it is a damn shame.

— Judith Roitman, Lawrence, Kansas, June 2017