Tansy

John Moritz (ed.), Lee Chapman (art ed.),

and others

Lawrence, Kansas

Nos. 1–5 (Spring/Summer 1970–Spring/Summer 1972).

Tansy 1 (Spring 1970). Front cover drawing by Lee Chapman.

In May 1968, John Moritz, a twenty-two-year-old student at the University of Kansas, wrote to poet Edward Dorn, whom he’d recently met in a writing workshop, about his plan to start an “art and poetry” magazine that would serve as “an extension of what we see and feel, capturing the electricity and energy of the moment.” The first issue of Tansy materialized two years later, in the spring of 1970, featuring work by (among others) Edward Dorn, Charles Plymell, Frank Stanford, George Kimball, David Antin, and a number of drawings by Lee Chapman. In all, nearly half of the contributors to Tansy 1 were either living in Kansas, or had at some point, and although the issue includes no editorial statement or any contributor biographies, the map of Lawrence (circa 1880) on its back cover, and the 1914 piece by Lincoln Phifer with which it begins—“beseech[ing] Kansans to break the literary domination of the East”—hint at the kinds of “extension” Moritz had in mind for Tansy to explore.

Tansy 2 ([1970]). Cover by John McVicker.

As many of our letters to the poets on the outside indicate, Tansy points—by that process of getting an issue together, getting it born—toward a set of lines & links, forces & signatures, to a locality we loosely call Kansas, & by the magnifying glass, Lawrence. Last May the Union burned. This summer two human beings were killed on the streets. The media came out with—“Shades of Quantrill.” We enter an age of struggle & adventure.

The first issue opened with a piece by Lincoln Phifer, written in 1914, when the fish were brain-food without the mercury connotation, and he beseeched Kansans to break the literary domination of the East, as they once broke the chains of the South. To seize the moment. We are at that moment in both time & geography. The work that appears beyond, is Now, as pulse, and Here, from a set of comparable meridians.

This issue opens with Jonathan Towers from Denver, at the end of the plains, not the beginning of the mountains. There are still the ghosts of riverboats that ran aground in Kansas City; then the horse, waiting on the railroad to lay out the prairie, the prairie commuted, then peopled. The Santa Fe tracks go west from Lawrence, first to Denver, then San Francisco. And the issue closes with the work of Richard Grossinger, whose Fredericton is a locality different, another place, than Lawrence, but still acting on & acted upon by the same elements & people trying to live there own life, determine their own power, their own chemicals of ingestion/digestion.

We learn by comparing/contrasting & this is—location. For the local, the sense isoutward, an introduction, and those of other directions are brought here, between these pages.

Shortly after the publication of Tansy 2—which also featured work by Clayton Eshleman, Jim McCrary, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Robert Kelly, and Anselm Hollo—the sense of adventure within the struggle suffered another heavy blow, this one much closer to the Lawrence literary community. Max Douglas, a twenty-one-year-old student from St. Joseph, Missouri, close friend of Chapman and Moritz, and a remarkably precocious poet, died of a heroin overdose in October 1970. From this point forward, the story of Tansy (the magazine) is inextricably bound up with Douglas’s tragic fate.

The death of Max Douglas is first mentioned in the “Late News” at the back of Tansy 4, which section also explains the whereabouts of Tansy 3:

Tansy 3 is a joint publication with Peg Leg press who is Jim Schmidt and appears out of the bottoms as a long, beautiful poem by Ken Irby, A Poem for Max Douglas. Tansy 5 will carry a large portion of Max’s work. He was a young poet from St Joe who died last October. The only work of his available to date were printed in Caterpillar 7 & 10.

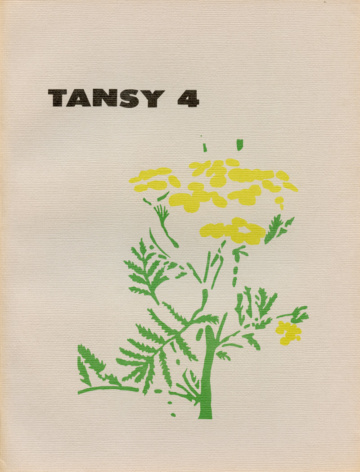

Tansy 4 ([Fall 1971]).

This has been a particularly difficult issue of Tansy to get finished. Some of the material has been in my hands for over a year. There are several reasons for this. One, for the last year and also the next, I have been the poetry hour chairman for Kansas University. Not that this has been overly time consuming, which is hasn’t, but with the quality of last year’s readings, I could not help but ask for something from everyone. So, it’s a question of saying “it’s finished” for those of you who felt your work waiting at the station. I think I’ve learned the lesson. Another reason, at the beginning, I saw this issue as some kind of statement on the death of Max Douglas. I think a statement has been made in this issue but not the one I began with. There were to be works by several people who expressed a desire to tell their story, all relating to Max in very different ways, i.e., the young poet, the impossible person, the tragedy of heroin. Those pieces never materialized. Instead, like always the magazine grew out of itself. Like the first issue grew out of a bookstore, the second out of a conversation with Clayton Eshleman and the fourth out of the flower. Ken Irby’s chapbook of course, grew out of its own soil.

In the future, Tansy will rotate an issue with a chapbook. The magazine will be published in the spring/summer and the chapbooks in the fall/winter. The next book of this series will be a collection of poems by John Morgan.

In spite of these plans, Tansy 5 was Moritz’s final issue, but the press continued. Moritz published books, chapbooks, and broadsides for another two decades, sometimes collaborating with other small presses, near and far. The Tansy pamphlet series runs to sixteen volumes, from 1976 through 1982, including titles by Ken Irby, Paul Metcalf, Harvey Bialy, Stephen Sandy, Bob Callahan, Richard Blevins, and Bob Grenier. And Tansy printed a total of seventeen broadsides, over half of which were issued in conjunction with KU Friends of the Library on the occasions of readings that Moritz organized for visiting poets, including Alice Notley, Ed Dorn, Michael McClure, Joanne Kyger, Tom Raworth, Robin Blaser, and Duncan McNaughton. Overall, Tansy’s longevity and impressive catalog stand as a vivid testament to the thriving but under-recognized literary community in Lawrence, and to Moritz’s lifelong resistance to the cultural hegemony of the coasts.

— Kyle Waugh, Brooklyn, March 2017

[1] Lee Chapman would serve as art editor of Tansy 5, before moving to New York with Kenneth Irving (an assistant editor, along with Brian Sulkis, of Tansy 1), where the couple coedited American Astrology Magazine. In the early 1990s, after Chapman had returned to Lawrence, she founded First Intensity Press and First Intensity: a magazine of new writing, which remained active through the early 2000s.

Tansy Pamphlets, Books, and Broadsides

Pamphlet Series

(1976–82)

Pamphlets measure 8½ x 5½ inches and are unpaginated. They include a short biography of the author on the illustrated verso of the final page, along with the following editorial statement:

The cover design is a collaboration between Lee Chapman and John Moritz. The original leaf of which the cover leaf is a reduction was sent to Tansy Press from Gloucester, Massachusetts. This series will appear randomly but, it is hoped, frequently and will be devoted to the work of a single artist.

Bialy, Harvey. From The Dance of the Fortune Chicken. September 1979. Tansy 11.

Blevins, Richard. Court of the Half-King. 1980. Tansy 13.

Callahan, Bob. At the Altar of the Fenians. 1979. Tansy 10.

Coues, Elliot (1842–1899), with an introduction and notes by Michael Brodhead. Two Fragments.

1978. Tansy 8.

Eshleman, Clayton. The Woman Who Saw through Paradise. N.d. [1976]. Tansy 2.

Grenier, Robert. Burns’ Night Heard. 1982. Tansy 15.

Gridley, Roy. PRC Diary – June 1982. 1982. Tansy 16.

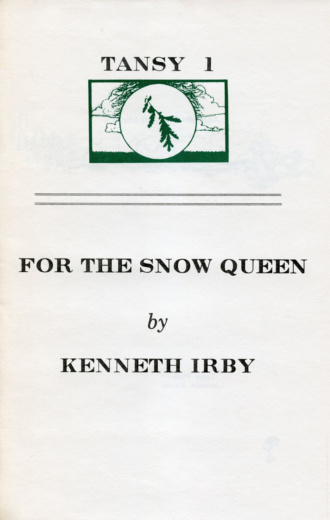

Irby, Kenneth. For the Snow Queen. 1976. Tansy 1.

Irby, Kenneth. From Some Etudes. 1978. Tansy 9.

Kahn, Paul. Memorial Day [31 May–1 June 76]. 1976. Tansy 3.

Metcalf, Paul. Upriver Farming and Industry: an excerpt from Waters of Potowmack, A Documentary History of the Potomac River Basin. 1977. Tansy 5.

Metcalf, Paul. Where Do You Put the Horse? 1977. Tansy 6.

Meyer, Thomas. Beautiful Rivers. 1981. Tansy 14.

Morgan, John. Grand Junction. 1977. Tansy 4.

Moritz, John. From The Heart Too Is a Flower, A Leaf. April 1978. Tansy 7.

Sandy, Stephen. The Hawthorne Effect. 1980. Tansy 12.

Kenneth Irby, For the Snow Queen (1976). Tansy 1.

Books (1971–92)

Blevins, Richard. Taz Alago: Pursuing the Five Tribes of the Nez Perce, 1877/1983. 1984.

Braman, Sandra. A True Story. 1985. Note: Published in conjunction with Zelot Press.

Byrd, Don. Technics of Travel. 1984. Note: Published in conjunction with Zelot Press.

Irby, Kenneth. Call Steps: Plains, Camps, Stations, Consistories. 1992. Note: Published in conjunction with Station Hill Press.

Irby, Kenneth. Catalpa. 1977. Illustrations by the author; cover illustration by Lee Chapman.

Irby, Kenneth. A Set. 1983.

Irby, Kenneth. To Max Douglas. 1971. Cover illustration by Lee Chapman. Note: Issued as Tansy 3 (misprinted as Tansy 4). Published in conjunction with Peg-Leg Press.

Irby, Kenneth. To Max Douglas (enlarged edition). 1974. Introduction by Edward Dorn. Cover illustration by Lee Chapman. Note: Published in conjunction with Peg-Leg Press; also includes the poems “Jesus” and “Delius.”

McCrary, Jim. West of Mass: Poems 1988–1991. 1992.

Metcalf, Paul. The Island. 1982.

Metcalf, Paul. The Man Blinded: an excerpt from I-57, a work-in-progress. 1976. Note: Published in conjunction with Skop Press.

Metcalf, Paul. Zip Odes. 1979.

Morgan, John. Intersections. 1972.

Moritz, John. Consentryks. 1985. Note: Published in conjunction with Zelot Press.

Moritz, John. Crossings I–IV. 1972. Cover illustration by Lee Chapman.

Parker, Linda. Graphite. 1980.

Wilk, David. Sassafras. 1973.

Broadsides (1971–91)

Only two of the broadsides (as far as I know) are numbered: #5 and #6.

Blaser, Robin. “Muses, Dionysus, Eros.” 1990. Note: “31 January 1990. / Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. / 100 copies have been printed of which 75 are for public distribution and have been signed and numbered by the author.”

Brotherston, Gordon. “Good Times at Tula.” 1973. Issued as Tansy 5.

Dorn, Edward. “Cocaine Lil.” 1975. Issued as Tansy 6. Note: Poem is not attributed to an author.

Dorn, Edward. “The Poem Called Alexander Hamilton.” 1971. Note: “From Book IIIIII / Chicago January / 1971 / Printed Lawrence / February 1971 / Tansy/Peg-Leg Press Publication.”

Irby, Kenneth. “[Planks turned to marble]: for Robert Kelly, for Ruth Palmer.” 1979.

Irby, Kenneth. “Restless, the rain returns …” 1980.

Irby, Kenneth. “Two Studies.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. January 25, 1989.”

Kelly, Robert. “Whaler, Frigate, Clippership.” 1973.

Kyger, Joanne. “The phone is constantly busy to you.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. March 29, 1989.”

Low, Denise. “Metamorphosis.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. January 25, 1989.”

McClure, Michael. “99 Theses.” 1972. Note: “A Tansy/Wakarusa publication composed at The House of Usher 1 February, 1972, Lawrence, Kansas.”

McNaughton, Duncan. “The see you later library.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. September 27, 1989. / 100 copies printed, of which 26 lettered and 50 numbered copies have been signed by the poet. Issued in conjunction with a reading by the poet.”

Moritz, John. “Cahokia Mounds” and “Reunion.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of KU Poetry Collection reading series. January 25, 1989.”

Moritz, John, and Lee Chapman. “Poems” (w/ illustrations). 1989.

Moritz, John, and Lee Chapman. “On whether or not the pig is indigenous to the New World: from I hear America cooking.” 1990.

Notley, Alice. “For Al.” 1990. Note: “31 January 1990. / Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. / 100 copies have been printed of which 75 are for public distribution and have been signed and numbered by the author.”

Peters, Robert. “There’s pain in gardening, as there is in writing poetry.” 1991. Note: “31 January 1991. / Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading series. / 100 copies have been printed of which 75 are for public distribution and have been signed and numbered by the author.”

Raworth, Tom. “Eternal Sections: Three Poems from a Sequence.” 1989. Note: “Published by Tansy Press in conjunction with the Friends of the KU Poetry Collection reading Series. February 28, 1989.”