Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K”

Andrew Schelling and Benjamin Friedlander

Berkeley

Nos. 1–9 (1984–89).

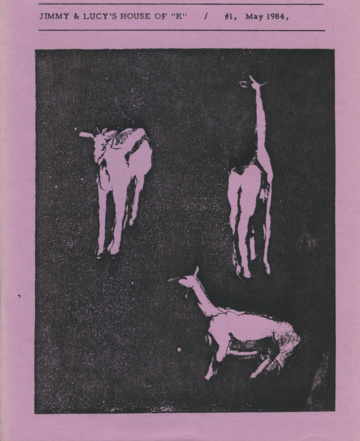

Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K” 1 (May 1984). Art by Nancy May.

Both language poetry and minimalism, with their attention to the small particles of writing, produced in the 1970s a lot of journals with names that were a single syllable or at least a single irreducible word. In 1984 that kind of title felt austere and predictable. We jammed together some little photocopy imprint titles and came up with Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K.” It began as a journal for poets writing about other poets. It quickly fetched up all sorts of odd prose items: writing that wasn’t quite essay, or manifesto, or epistle. The content strayed too—pieces on contemporary music, obituaries (not just poets but astrologers, musicians, experimental filmmakers, Buddhist lamas), hashish in Afghanistan, animal rights, vinyl record collections, and military slang.

Since the journal ran hardly any poetry, but that’s what most of its contributors wrote, we began to include in each issue a fugitive little chapbook by individual authors. It was hard to keep track of these inserts, which got produced in different sizes and shapes, and on a different schedule than the magazine, so journal issues and their chapbook accompaniments often got separated. Let the bibliographers figure this one out, we said. We titled the inserts “Lucy Has More Fun.”

If the titles seem juvenile, the work of producing the magazines was anything but. Ben had an old IBM Executive typewriter, huge heavy machinery, its keys badly worn. Its chief virtue was that it laid out letters so they resembled typesetting. Most typewriters have a uniform width for every key, but the Executive had variable spacing, so thin letter i or l got two spaces, thick m or w got four. The rest of the production was Exacto knives, white-out, and rubber cement. Then we photocopied it on legal-size paper. The crew at Krishna Copy in Berkeley took a liking to us. They gave us very cheap prices for copies, and let us use their industrial paper cutter, saddle stapler, and other tools that we needed. There is no way to know how many copies of each issue we made. Typically we’d make a first batch to cover subscribers, which included some libraries, and a few to drop off at local bookshops. When we ran out we’d head down to Krishna and make up another ten or twenty. Surely no issue had more than two or three hundred copies.

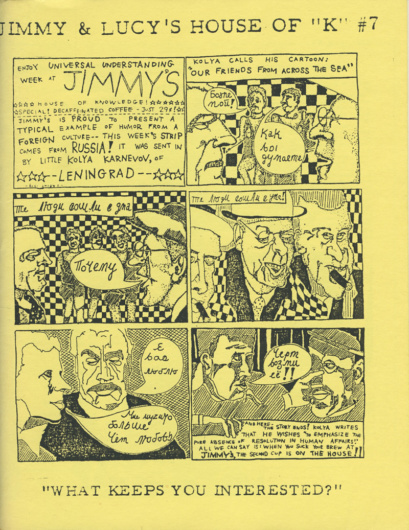

Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K” 7 (December 1986). Front cover by James Recht. This issue includes the insert Lucy Has More Fun that publishes Pat Reed’s “5 Poems from Qualm Lore.”

Of the nine issues, each third one was a special theme issue. Number three greeted Robert Duncan’s return to publishing with Ground Work: Before the War, after his book moratorium of fourteen years. A review that the San Francisco Chronicle had requested from Ronald Johnson, then rejected as too esoteric, was emblematic of the kinds of things we could and did publish. Issue six commemorated the fifty titles Lyn Hejinian had published (and printed) under the Tuumba Press imprint. We got somebody to write on almost every one of the Tuumba chapbooks. Issue nine, our final one, carried the transcript of a weekend on Buddhism and poetry that Norman Fischer had put on at Green Gulch Zen Center. For this, “The Poetics of Emptiness,” David Sheidlower printed a letterpress cover, using Lyn Hejinian’s old Chandler & Price platen press.

Nada Gordon proofread with us. Pat Reed and Stephen Rodefer occasionally helped with typing, or cut and paste. Lots of the young experimental writers around the East Bay, alongside language poetry elders, contributed the writing. Some of the New American poetry generation gave us pieces as well. Larry Eigner, Leslie Scalapino, Charles Bernstein, Rachel DuPlessis, Philip Whalen, Nathaniel Mackey, Susan Howe, Carla Harryman, Bob Grenier, and always work by the editors, typists, and proofreaders. Nobody ever questioned how homemade, funky, or non-establishment the thing looked.

— Andrew Schelling, Boulder, Colorado, January 2017

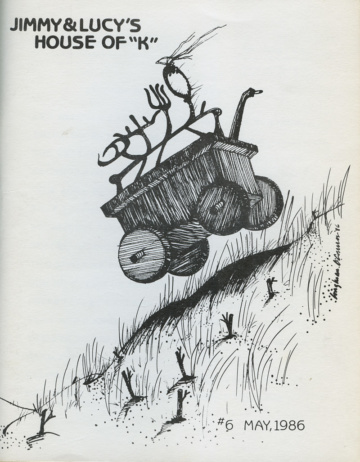

Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K” 6 (May 1986). Cover by Loughran O’Conner.